Lance Corporal John William Sayer VC

8th Bn The Queen's (Royal West Surrey) Regiment

|

| Lance Corporal John William Sayer VC |

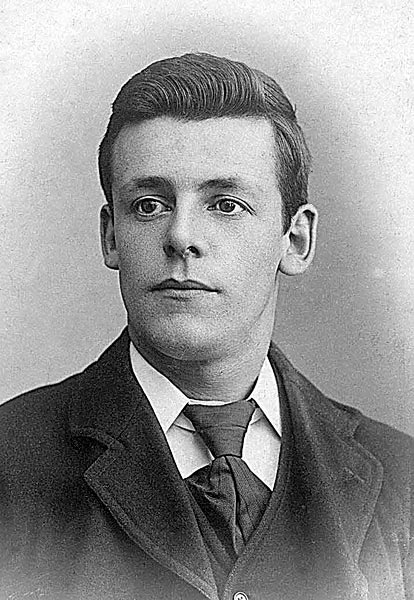

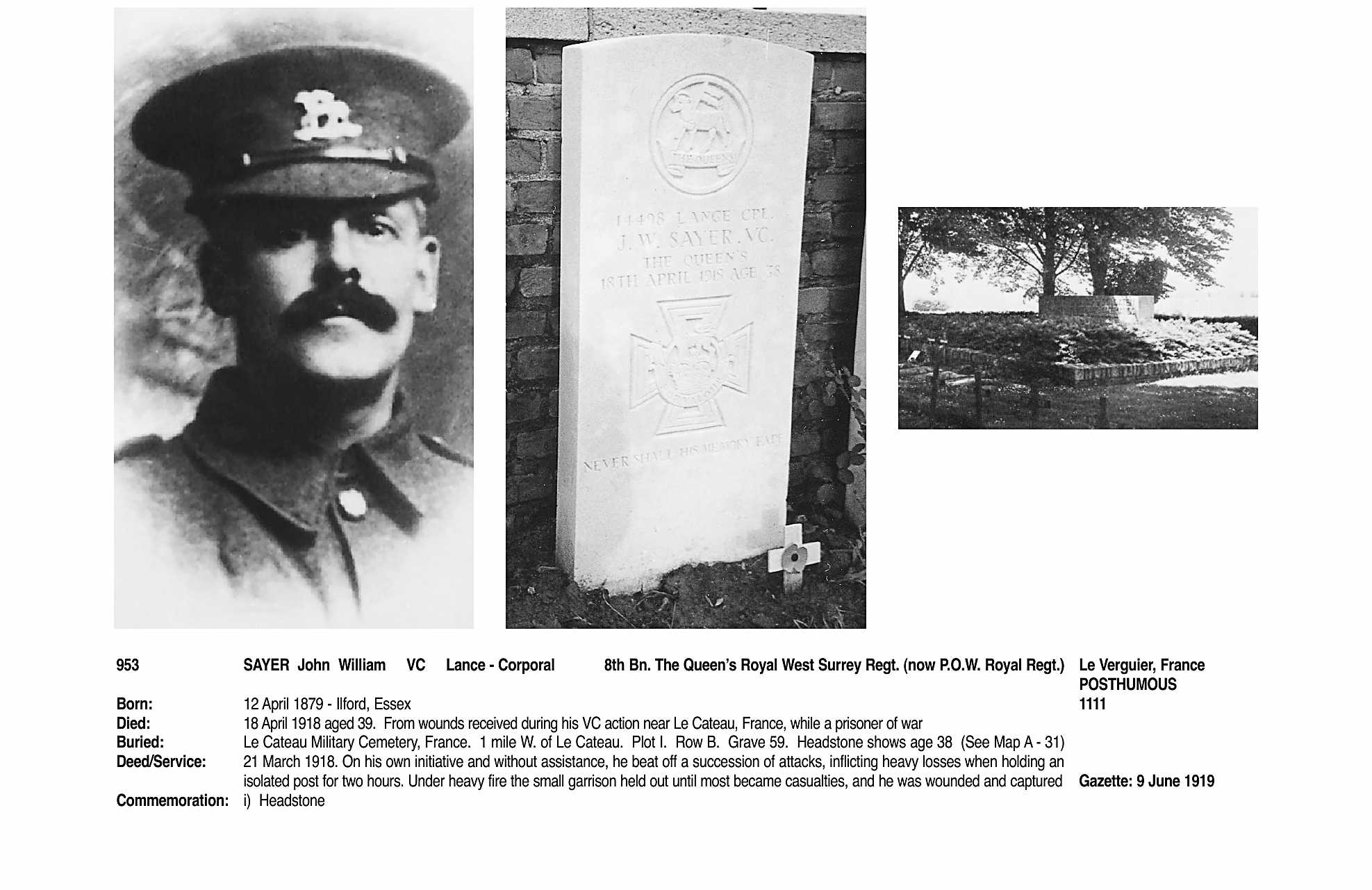

Born in Islington on 12th April 1879, J W Sayer spent much of his early life in Ilford, Essex. He joined the Army on 25th July, 1916 and served on the Western Front from December 1916 until he died from wounds at Le Cateau in 1918. He was buried in Le Cateau Cemetery, France, Plot 1, Row B, Grave 59.

John William Sayer was the son of Samuel and Marguret Sayer. His father was a farmer and the family home was at Wangye Hull Farm, Chadwell Heath. Apparently the Sayers had lived in the area for several generations.

His Citation reads:-

“For most conspicuous bravery, determination and ability displayed on 21st March 1918, at Le Verguier, when holding for two hours, in face of incessant attacks, the flank of a small isolated post. Owing to mist, the enemy approached the post from both sides to within thirty yards before being discovered. L/Cpl Sayer, however, on his own initiative and without assistance, beat off a succession of flank attacks and inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy. Although attacked by rifle and machine-gun fire, bayonet and bombs, he repulsed all attacks, killing many and wounding others. During the whole time he was continuously exposed to rifle and machine-gun fire, but he showed the utmost contempt of danger, and his conduct was an inspiration to all. His skilful use of fire of all description enabled the post to hold out till nearly all the garrison had been killed and himself wounded and captured. He subsequently died as a result of wounds at Le Cateau”.

Date of Act of Bravery |

London

Gazette |

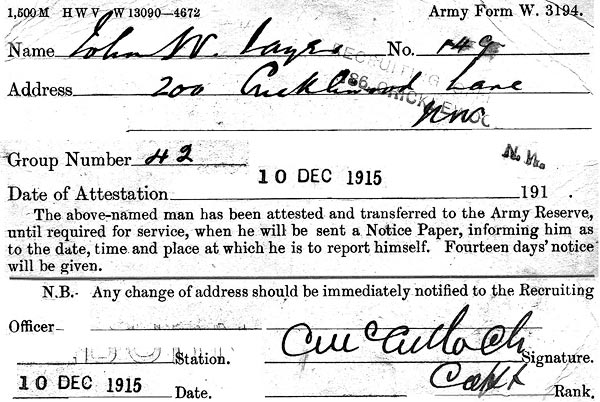

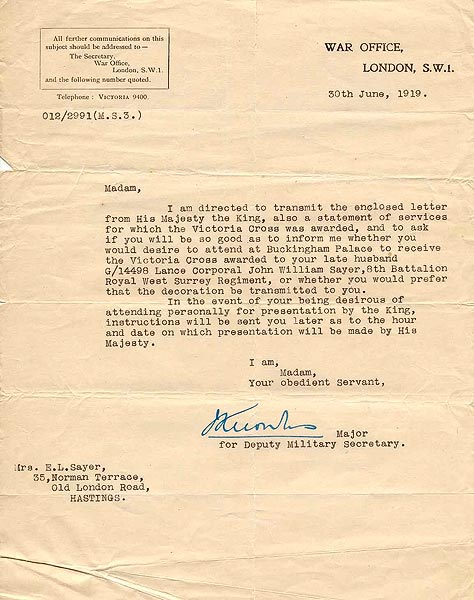

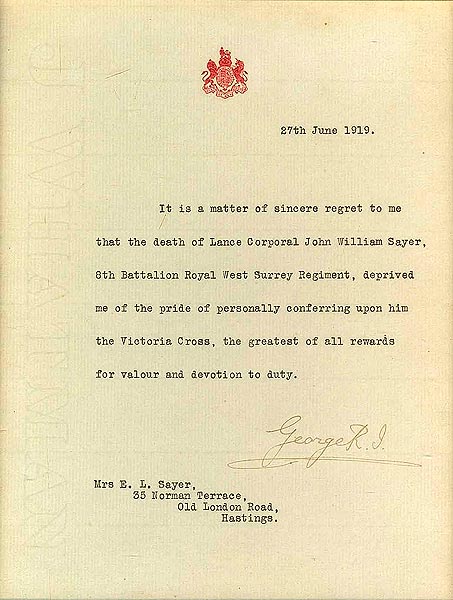

Sayer went to school in Illford and married Edith Louise Maynard of 35 Old Lower Road, Hastings in Illford Parish Church on 15 August 1904. Over a period of thirteen years he and his wife had six children, four daughters and two sons. It seems that he left Ilford and went to Cricklewood, were he ran a corn and seed merchant's business. His parents still farmed in Chadwell Heath and he joined up on 25 July 1916, went to France in December 1916 and was promoted to Lance Corporal in 1917. His VC was gazetted on 9 June 1919. Sayer's widow recieved her husband's VC at Buckingham Palace from King George V on 16 November 1919.

Editors Note. This reappraisal of one of our Victoria Cross holders was written by David Baker, who for many years felt that Sayer had not been given full credit for the actions of 21st March 1918. True, his gallant action was recognised by the award of the Victoria Cross in 1919, but by then his Battalion had disbanded and the two officers who fought to have Sayers gallantry brought to the attention of the public had themselves left the army. No mention of Sayer is made in the Regimental History. This is inexplicable. It is of course true that the war diaries do not record the full story. The puzzle is even more baffling when looking at old recruit booklets all record his name & citation, and on all regimental rolls of Victoria Cross holders his name is shown. This article shows how a largely unknown two hour stand had consequences which, because 21 March was a pivotal day, may have influenced the outcome of WW1. It explains not only how the stand itself came to be forgotten, but also why the consequences, although appreciated at the time, were later ignored. |

John Sayer VC and the 21st March 1918:

A new appraisal of a forgotten hero

| John Sayer, age 21. Enlarge Image |

John William Sayer went to France in 1916 as a machine gunner in the Queen’s Royal West Surreys and in 1917 was promoted to Lance Corporal. At about 10.00am on 21 March 1918, as the long-awaited advance associated with the German spring offensive began, he single-handedly seized and defended a strategic position at Shepherds Copse close to the Hindenberg line north-east of Le Verguier. His bravery citation describes how, ‘for two hours on his own initiative and without assistance, he held the flank of a small isolated outpost and beat off a succession of attacks, inflicting heavy losses’. He was wounded, losing a leg. He died four weeks later in German captivity, aged 39, leaving a widow and six children, and is buried in Le Cateau.

The spring offensive, which very nearly won WW1 for Imperial Germany, had opened at 4.40am. Martin Middlebrook in The Kaiser’s Battle estimated that by midnight on the 21st the dead and wounded totals were nearly 40,000 German and about 17,500 British. Another 21,000 British soldiers had been captured, making this one of the highest single day's casualty tolls of any war. Middlebrook concludes ‘21 March 1918 was the beginning of the end of the First World War’. The offensive had been intended to land a knock-out blow, but the maximum advance before the campaign's abandonment 16 days later was about 40 miles. Compared to the gains of the previous four years this was substantial, but not nearly enough to achieve the aim of driving the British back to the North Sea.

| John & Edith 1917. Enlarge Image |

German armaments and men far outnumbered British resources; and no one who experienced the ferocity of the onslaught ever forgot it. Winston Churchill described the five hour salvo along the 50 mile British front which preceded the German advance, as ‘the most tremendous cannonade I shall ever hear’. It was said the guns could be heard 200 miles away in London.

John Sayer's deed was witnessed by his platoon commander Lieutenant Claude Lorraine Piesse who, with Colonel Hugh Chevalier Peirs of the 8th Battalion of the Queen's Royal West Surreys, recommended him for a Victoria Cross.

Piesse's report of the incident, now in the Surrey History Centre, describes Sayer ‘defending against all attacks of the very much stronger enemy by bayonet and rifle with almost incredible bravery'. Due to thick mist fighting was often hand-to-hand, and only at noon with the fog clearing and Sayer badly wounded were the Germans able to capture his position. Piesse says ‘Although for two hours he was continually exposed to enemy machine gun fire and bombs, he used his own rifle as coolly as if at the butts'. He concludes ‘Sayer showed the utmost contempt for danger and the enemy and inspired everyone by his conduct'.

But the Shepherds Copse stand is virtually unknown. This is only partly because John Sayer's VC citation wasn't published until 15 months after the event (and, as became clear, only told half the story). And only partly because by 1919 compassion fatigue meant that people had become tired of reading about heroes.

Sayer is also missing from the majority of VC battle literature and most WW1 books, notably his own regimental history. The accounts that appeared in the 1920s contain errors, including an incorrect date for his VC deed. His file at the Imperial War Museum contains only two half-sheets of paper, one of which still perpetuates the clerical mistake that he won his VC on 31 March.

| Sayer children 1918 Ivy Louise in centre. Enlarge Image |

Those who seek further information about Shepherds Copse or indeed search for any reference to Sayer in the obvious source, his regiment's official record of the period, do so in vain. The History of the Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment in the Great War by Colonel Harold Wylly, published in 1925, contains no mention of him, or of Shepherds Copse. There were actually two Great War VCs in the West Surreys' Battalions, but only Sayer is ignored. In contrast, Wylly, a professional writer, devotes several pages to describing the deed of their second VC. Possible explanations are considered later. For more understandable reasons Sayer is also absent from his Battalion’s war diary. But the result is that while other VCs are recalled on memorials, street signs or cigarette cards, Sayer is forgotten and the significance of his place in WW1 history remains unknown.

His invisibility isn't helped by the lack of any record of his service career, which in fact included a previous act of exceptional bravery in August 1917; or by the fact that his family has never allowed public display of his VC medal.

So because he isn’t in the reference sources used by later authors and has no UK memorial; and because the mistake in dates divorced him from the action in which he featured; John Sayer is in limbo, an unknown VC, usually overlooked. But in spite of this neglect fresh facts about his involvement in the tide-turning events of 21 March were waiting to be uncovered after nearly nine decades.

The 'new' sources are various notes made by Claude Piesse himself and a 1918 letter to him from Hugh Peirs. Piesse's habit of recording his conversations with Peirs verbatim helps. Although many of these documents are in London (in the Imperial War Museum and in King’s College) others are still with Piesse’s family.

| Attestation 1915. Enlarge Image |

Another useful source on the battle itself is the diary of Captain Charles Lodge Patch, the 8th Battalion’s senior medical officer. This too is in the IWM. Patch went on to publish two vivid descriptions of his experiences on the 21 March: one for his old school magazine and the other in an obituary of Colonel Peirs in 1943.

Robert Ward, a WW1 researcher and great-nephew of one of Sayer's comrades, found that Piesse had visited the military historian Basil Liddell Hart at his home in 1951 to discuss aspects of March 1918. Piesse had told Liddell Hart that he had kept many papers from WW1. This posed the question of whether these might still exist and could provide additional information. But the only clue to the papers whereabouts was Piesse's 1951 address in a suburb of Perth in Australia.

An internet search uncovered a website for a school in that suburb. The Piesse name is not uncommon in Western Australia and the school actually had a Piesse on their staff, although this proved a false trail. More positively a request to the school's principal seeking help led to contact with a parent who undertook to trace Claude Piesse's descendants.

Using impressive detective work the parent discovered what had happened to Claude Piesse’s family in the 50 years since they had lived in the Perth area. Although the original Piesse home had long since vanished, she located and talked to Piesse's sole descendant, his daughter, now living in retirement in a small town several hundred kilometres distant. Most exciting, Piesse's daughter, who already knew about John Sayer from her father, had kept most of his papers. A phone conversation with her suggested her father’s letters and journals were well worth visiting Western Australia to read.

| Investiture. Enlarge Image |

Piesse's daughter had dozens of fascinating memories of her father and his English friends, including Hugh Peirs. And Claude Piesse himself was clearly an interesting character. Although born in London, where his father had founded a well-known Bond Street perfumery business, he had settled in Australia in 1899, managing a remote station. He already had family connections there, an uncle having been Colonial Secretary for Western Australia.

Highly educated and a linguist, when WW1 started he was rejected as too old for the Australian Army. So in 1915 he returned temporarily to England to serve in the Queen's. His Australian independence and curiosity (he frequently questions the ‘establishment’ view) makes him an ideal reporter. He also had a particular interest in the Arts, and was a life-long friend of the laureate John Masefield and Eric Kennington, whom he first met as a war artist. A 1918 Kennington painting of the Le Verguier front line, which may depict Sayer, is now in Perth art gallery.

Piesse’s papers included various eye-witness descriptions of the war in France expanded from his contemporary diaries. Then towards the end of his long life Piesse had prepared a fresh account of his experiences on 21 March (the IWM has a copy) as a memorial to the men of his platoon who had died.

In fact a total of about seventy Queen’s soldiers, including perhaps twenty at Shepherds Copse, were killed during the fighting for Le Verguier. Only a dozen of the seventy have known graves. But casualties in the village itself would doubtless have been substantially higher without the postponement of the main attack on the 21st followed by the smooth withdrawal on the 22nd, during which not a man was lost. Both are described in detail below.

Among Piesse’s papers there was one key document of particular relevance to Sayer. This was a two page letter written to Piesse in his German prison camp on 27 August 1918 by Hugh Peirs, who was still commanding the 8th Battalion in France. Piesse had described Peirs to Liddell Hart as ‘quite the cleverest and finest officer of any rank with whom I came into contact during my years of service’; a view echoed by Patch both in his own diaries and in Peirs obituary.

The Peirs letter is a response to one, now lost, sent by Piesse to a fellow officer named Burnham describing what had happened in the front line outposts, about a mile north-east of the Battalion's main position, on the morning of the German advance. Piesse’s command at Shepherds Copse in fact included three separate posts connected by trenches. These were initially defended by twenty-two men, although men from other positions (the fog made it impossible for Piesse to record exactly how many) joined during the fighting.

Due to an earth mound which limited the eastward view the Shepherds Copse trench complex was not ideal for defence, even without the fog. Piesse notes the defenders had no grenades, only limited rifle ammunition and no palatable drinking water (supplies having been stored in kerosene drums).

The position which Sayer had seized at the junction of two communication trenches, although open to enfilades, provided the only effective sight on the advancing enemy. Fluctuating visibility meant fighting was sometimes at close quarters and Piesse describes how, in repulsing repeated attacks along the trench, Sayer single-handedly killed six attackers with his bayonet while dropping others with his rifle. As he was being taken away at noon Piesse, although semi-conscious, counted nine bodies he believed had been killed by Sayer, almost certainly an underestimate of the actual total. For most of the two hours Sayer endured a continuous hail of machine gun fire and grenades in a manner Piesse found near miraculous: ‘it was a wonder to me every minute that he did not fall’.

Before considering Peirs' letter, there is other evidence about both the strategic importance of Shepherds Copse and the delayed advance on Le Verguier.

| The Kings letter. Enlarge Image |

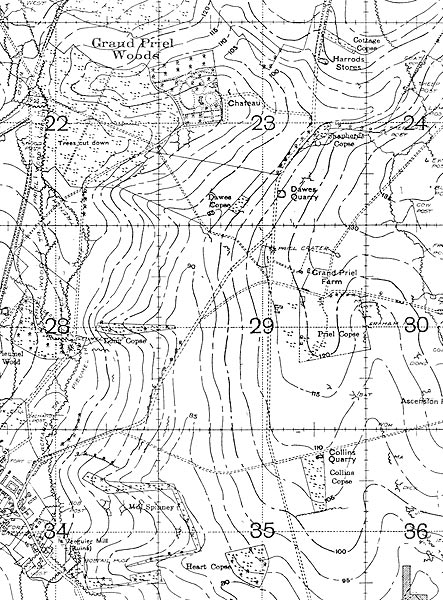

First, the dominant position of Shepherds Copse at a bend on the road which runs along the valley from Le Verguier to Villeret, on the south-west side of the old 1918 Front Line, is still apparent today. The map used by the 8th Battalion, annotated at the time of the March offensive and now in the National Archives, indicates that the main thrust of the German advance on Le Verguier came through this valley, having to negotiate Shepherds Copse on the way.

Second, although shelling of Le Verguier had commenced before the attacks on the outposts, the German assault proper on the village did not start until 3.00pm. The only explanation we have for the lateness of the assault, and the one that Peirs later accepted, is the morning's hold-up at Shepherds Copse, which was unknown to the defenders in Le Verguier at the time.

The fog’s persistence and the delayed attack had provided time for defensive regrouping, so that by noon men from abandoned outposts had moved to strong points in the village. By contrast the units on either side of the 8th Battalion (a battalion of the 66th Division on the left and the 3rd Rifle Brigade on the right) had been pushed back earlier, so that Le Verguier then stood, as Peirs later told Piesse, ‘at the point of a narrow peninsula extending into enemy territory'.

There is more about the situation in the village in Patch’s diary. During the morning the very thick fog disoriented everyone. Patch's main medical aidpost was in a quarry a few hundred yards north of the village, but he became lost in the fog trying to reach it from Battalion HQ and, because he had inadvertently swallowed some gas, had difficulty getting back. Communication with Piesse’s platoon had been lost very early. Shepherds Copse was therefore assumed to be in enemy hands as, according to escaped survivors, were the other outposts.

A captured German officer who spoke French and who had been injured by a Mills grenade was questioned by Patch as he dressed his wounds. The officer told him that their plan had been to take the village within two hours as a first step towards eventually pushing the British back to the coast. The village standing on high ground and containing numerous strong points was in fact eminently defendable in clear weather providing sufficient men were available to staff the forts. So the German timetable presumably depended on completing the attack under fog cover, which the Shepherds Copse hold-up had frustrated.

| Ivy Sayer, at a Remembrance Day. Enlarge Image |

Patch, Piesse and Peirs all believed that the German advance had been aided by, and almost certainly planned to take advantage of, the predictable morning fog at that time of year. The British command apparently lacked any specific retaliatory strategy. During an earlier discussion with a Divisional artillery officer Piesse had asked about fighting in fog.He had been told 'we have no orders'.

Colonel Peirs, who according to the Battalion diary reached Le Verguier at 7.00pm on the 21st from Bernes, spent the night directing the village’s defence.But he withdrew early on the 22nd aware that by so doing he was disobeying orders. Piesse observes that a similar instruction to fight to the last was the reason that three-quarters of his own platoon were killed. Piesse records that a Red Cross stretcher-bearer had told him that his platoon had never surrendered since no one still alive, including Sayer, Piesse himself, and a handful of others, was standing and able to give the order when the position was finally overrun.

Peirs told Piesse in London after the war that he had received a telephone call from Brigade HQ during the night of 21st instructing him to hold his position. But he went on to say 'as I had still over 300 men left they would be of much better use in the line than in a German prison or dead, so I decided to disobey orders and retire'. Few today would query Peirs’ logic, or the foolishness of the order. The morning withdrawal on the 22nd was aided by a repeat of the thick fog which had helped the Germans on the previous day. Peirs described how they could hear the Germans talking on either flank as they retreated, with no loss of life, through a narrow corridor. His judgment and leadership here were exemplary.

Returning now to Peirs’ August 1918 letter discovered in Australia, its gist is summarised in the opening paragraph: ‘Burnham has shown me the very wonderful letter you wrote him, which I think is the finest letter I ever read. This is the first inkling l have got of what occurred in the front line on the day in question and I (am) sorry that we have not been able to do full justice to the conduct of those who played their part so well and enabled us behind to hold out so long and the Battalion to be specifically mentioned'.

Until reading Piesse’s account of events at Shepherds Copse Peirs had apparently lacked an explanation for the delay in the assault on Le Verguier. The postponed attack had allowed the Battalion to maintain its position for longer than any other unit on the entire British front, which had led to commendation in the Commander-in-Chief’s dispatches.Peirs wants to assemble evidence for an award recognising the delaying action and he asks Piesse to send further details of Sayer’s and two of his comrades’ specific roles, with corroboration.

So thanks to German leniency in allowing uncensored correspondence between an enemy officer and a prisoner; and Piesse's foresight in retaining a revealing letter; for the first time we have a measure of the importance of Sayer’s action.

| Shepherds Copse. Enlarge Image |

The existence of the Shepherds Copse stand had previously been unknown and its impact had therefore been uncalculated. Because communications with the outpost had been severed early the action isn't included in the Battalion’s contemporary war diaries. And, as already remarked, it’s also missing from the much later official regimental history. Piesse had described the history in a note to Liddell Hart as ‘not worth reading except one considers it a fairy tale'.

But, above all, the letter anticipates and explains Peirs later very strong support for the VC nomination. Although when Peirs wrote he was still awaiting full confirmation of Sayer's role, his letter indicates he believed the Shepherds Copse stand was the major reason for the delay in the German attack, which had preserved so many lives and enabled the 24 hour resistance.

So it’s curious that neither of these facts is included in Sayer’s VC citation of June 1919, quoted at the start of this article. It’s particularly bizarre that the delaying action and its life-saving consequences aren’t mentioned even though in August 1918 Peirs had apparently intended to recommend an award for Sayer recognising these dual effects. Could there be a reason for his change of heart?

The explanation appears to be that by the time Sayer’s citation came to be written all credit for the delay had already been given to someone else: Peirs himself. He was awarded a second bar to his DSO in September 1918. His citation reads ‘For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in defence of a village, when he fought until surrounded, and then made his way back under cover of a fog. It was entirely due to his great courage and fine leadership that the enemy offensive was delayed for nearly two days'.

Leaving aside the fact that the 24 hours had been stretched to two days, one might assume that the comprehensiveness of Peirs’ citation precluded giving Sayer any credit for Le Verguier's lengthy resistance. Theoretically Peirs’ award should not have influenced Sayer's 1919 citation (as in principle new evidence can replace previous assumptions) but it undoubtedly created complications.

The 8th Battalion’s reputation in response to the 1918 spring offensive had become well-established without acknowledging Sayer. Their success had been applauded in British newspapers, notably The Times of 26 March which had praised them under the headline ‘West Surreys Fight to Last Man’; they had been mentioned by General Haig; and their CO had been decorated for resistance ‘entirely due to his great courage'. Announcement of the effects of Sayer's action would mean reapportioning credit, unsettling this cumulatively built reputation.

Therefore if Peirs was to obtain Sayer his award, which apparently met some opposition, the safer approach would be to limit any description of events to those Piesse had observed; not to extend it to the consequences the rest of the Battalion had experienced. Moreover arguing that his own recent citation lacked accuracy would, at the least, have caused a respected officer like Peirs embarrassment. But in the event it appears that evidence about the effects of the Shepherds Copse stand wasn't actually required as support for Sayer's VC nomination. So, almost inevitably, it failed to become part of Great War history.

| John Sayer's Medals. Enlarge Image |

When it came to writing the regiment's official story six years later (and a final opportunity to do Sayer justice) there are two possible explanations for his exclusion. Perhaps Wylly was ignorant of the VC award because his research was perfunctory. The 8th Battalion had by then been disbanded and assuming their war diary, which omits the Shepherds Copse stand, was Wylly's sole source of information, this theory seems plausible. On the other hand most Royal West Surrey officers must have known about Sayer's VC which had been reported in the national press and in at least three books by the time Wylly wrote. And a careful reading of his relevant chapter shows that Wyllie did consult other sources besides the diary.

So Sayer’s absence remains a mystery. But whatever the reason one can understand Piesse's 'fairy tale' gibe and can only guess what other omissions the history may contain. And indeed on this evidence whether any other regimental history by Wylly (he wrote several) can be trusted. Piesse suspected that Wylly believed that the deeds of volunteer soldiers simply weren't worth chronicling: ‘if ours had been a regular battalion the writer would have been more generous'.

The hint that the VC recommendation met resistance is in a letter from Piesse to Sayer in March 1919. Neither Piesse, nor Sayer's widow, then knew that he had died eleven months previously. The letter says Peirs is doing all he can but may not succeed. But a month later Piesse recorded that the VC nomination had not been turned down, but returned to Peirs by GHQ for removal of 'some paragraphs in which exceptions were taken'. Copies of the earlier nomination were destroyed; so we can only wonder whether any of the censored paragraphs may have mentioned Sayer’s role in delaying the assault on Le Verguier.

|

| John Sayer's Gravestone. |

Sayer's nomination will also have received particularly lengthy scrutiny because it related to an award for an action which had culminated in his capture. Bravery medals weren't given in these cases, although exceptionally a VC could override the rule.

The fact remains: had Sayer's citation acknowledged any of the consequences of his action which we now know had been recognised by Peirs; and had the regimental history been written with genuine objectivity; Sayer might have been remembered today as some thing more than a soldier who 'beat off a succession of attacks'.

He might at least have been linked to the preserving of a number of his comrades lives and freedom, and credited as such by later commentators. As it is his isolation from the events he influenced continues. Even a recent and carefully researched book on WW1 battles, which describes Le Verguier’s defence at length using regimental records, not surprisingly overlooks him completely.

Piesse had told Liddell Hart that conversations with German soldiers and civilians as a prisoner had convinced him that the slide in German morale which cost them the war dated from 21 March, when things went wrong from the outset. German objectives for the spring offensive were over-ambitious, but the now forgotten 24 hour delay in taking Le Verguier was obviously a key factor making the 21st a pivotal date. Therefore men like Sayer deserve credit for hastening the Allied victory. Denial of this credit, as well as denial of the other consequences of his actions, is an unnecessary stain on his memory.

In summary therefore the Peirs letter, and the other research which led to its discovery, redefines the contribution that John Sayer's sacrifice made towards winning this devastating war. His action should therefore now be considered as an act of bravery which achieved something beyond the solely inspirational.

(Click image to view enlarged)

Related Links

External websites: