Queen's in the Middle East

The Actors Leave The Stage

Although all resistance in Tunis and Bizerta had ended by the morning of the 8th May, events were not so clear-cut on the Eighth Army front at Enfidaville. The whole area had become covered with minefields, some long forgotten or unknown by both sides, added to which there was some confusion about who was surrendering and where. Most Germans surrendered on the 12th, following General von Arnim’s capture, but Field Marshal Messe’s Italians officially held out until the morning of the 13th. General Alexander was unable to send his famous signal to Churchill until 12.15pm on the 13th May:-

“Sir, |

Capt John Creek has left an interesting and humorous account of the surrender at Enfidaville, illustrating some of the confusion within Eighth Army at this time:-

“I was Adjutant of the 2nd/7th Queen’s - the CO was Col. A.P. Block-when the final surrender of the Axis Forces was taken outside Enfidaville. Since that day I have read various reports on that particular surrender and seen one or two variations of it on both British and Italian TV, leading to the conclusion that the writers or the producers involved had not done their homework properly and in consequence gave a description or representation far out of line with what actually happened.

The 2nd/7th Battalion of the Queen’s Royal Regiment were still holding the Eighth Army front line from the sea across the only road in that piece of North Africa and to their left, where they joined up with one of the other Queen’s Battalions. We, the 2nd/7th, had one company to the right of the road, between the road and the sea, and two companies on our left front, on the left of the road. For two or three days before the actual surrender there had been some coming and going of Italian and German prisoners through our front line, carrying messages, proposals of surrender, from the rear to the Axis command.

Early on the morning of the day of surrender, 13th May, the 169 Brigade Major, Major Desmond Gregory, called me on the nine set and said that the Battalion should prepare the site for a surrender ceremony at three o’clock in the afternoon on the road which bisected our front, at a point where our forward companies were dug-in.

Jokingly - he was a Regular officer and I was not - I asked him how exactly one took a surrender, and he, equally lightheartedly, referred me to my Field Service pocketbook. This bulky pocketbook I looked through from end to end, but found no instructions on how a unit of the British Army should take a surrender. When I called him back on the nine set, he said he had been looking too, and he could not find any pamphlet to help us.

In the event, we placed men with Bren guns on each side of the road at the very limits of the line as we were holding it, and men with Bren guns on each side of the road thirty or so yards further ahead into No-Man’s-Land. Between these two machine gun posts on the roadside, we marked off areas where surrendering troops would deposit both arms and everything else they were carrying. We also set up a blocking point on the road, level with our reserve company and headquarter’s company units, to make sure that military “visitors”, knowing the war was over for ever in North Africa, would not decide to come up and see what life in the front line was like, and get under our feet whilst we were getting on with the job of receiving surrendering troops, both officers and men, and sending them in an orderly way to the rear.

The surrender time was fixed for three o’clock; and, all the morning, flights of light and medium bombers pounded the escarpment in front of us, which was a mass of 88mm guns, mortars and retreating troops of every sort who had not been able to get up to Bizerta and away to Sicily.

Before three o’clock the surrender area was completely empty except for Col. Block and myself, but then the reception party arrived. First the Brigadier, L.O. Lyne, and his Brigade-Major, in a jeep. Immediately after, the Divisional Commander and his acting GI. Both were “newcomers”; Brigadier (acting Major General) “Noisy” Graham had come to the Division only a few days before from the Highland Division when our Divisional Commander, Major General Miles, Grenadier Guards, was severely wounded and flown back to England. His GI, Lt.-Col. Tam Ely, KSLI, had been killed in the same incident. They came in a scout car, quickly followed by the Corps Commander and his Chief of Staff. The last vehicle to arrive was a Sherman tank, which brought up General Freyberg, VC, and a staff officer. General Freyberg was acting Commander of the Eighth Army because General Montgomery had, in these last days of fighting in North Africa, taken a large force round on what some people called the Left Hook, to support the First Army’s drive through from the west, while the 8th Army held the line firm at Enfidaville.

In the half-hour before three o’clock the bombers had been over and gone away for the last time and silence had fallen all over the battlefield except for explosions facing us and to our left in the hills, where German units, in defiance of the surrender terms which had been accepted, were spiking their guns.

By a quarter to three a dark, wide column of troops could be seen coming up the road towards us a mile and a half or so away. At this point, while the reception committee stood about and chatted, and with no one any longer wearing a steel helmet, a gun was fired away to our left along the line of our front at a low trajectory, and a round passed over the reception party’s heads. As one man, all the distinguished and high-ranking members of the reception committee and their staff aides were on their stomachs and crouching against their vehicles. The shell landed in the sea, and as there was no explosion we concluded it must have been solid shot. No second shot followed, and gingerly the reception party got to their feet again and looked towards the south, from whence the shot had come. Naturally, the queries and comments filtered down rank-wise until the Brigadier came up and asked Colonel Block and me, standing with him, what on earth was going on and what we were doing about it. I quickly got an officer and four or five men going at the double inland, as it were, and later in the afternoon we got the explanation of the single and highly disturbing shot.

As they had withdrawn, Axis units, knowing that they would never again advance in North Africa, had taken up every marker they could find on minefields they had laid to protect themselves. In this case, a small unit with an 88mm gun in an anti-tank role, posted to fire from south to north across our Divisional front, towards the sea, on seeing their comrades marching in thick rank up the road to surrender, had decided they would like to do the same, but they were unwilling to try a cross-country route to join the surrender on the road because of the minefields. So they put one round of solid shot into their high velocity 88mm gun and fired it into the sea to draw attention to their plight, and thereby had succeeded in giving the reception party a nasty surprise, when they thought all firing was over for ever, at least in this theatre and campaign.

Not unexpectedly, some Italians and Germans, seeking to short-cut to the road and join in the surrender, did destroy themselves on their own minefields; and one party stumbled onto a field of S mines sufficiently near our C Company front line to cause casualties among that Company’s troops, now out of their slit trenches and in the open, watching the surrender from a distance. The Company Commander, Captain Mike Charlton, was one of the casualties. He survived, but never fought again, and the wounds he suffered that day affected him for the rest of his life.

(Author’s note - Mike Charlton was OC ‘B’ Company, who happened to be visiting Maurice MacWilliam, OC ‘C’ Company, when wounded.)

By the evening the total of men surrendering was around 38,000, of whom 28,000 were Italians and 10,000 Germans. The act of surrender was made to the acting Eighth Army Commander by General Messe, commanding Italian troops still in North Africa, and by General von Arnim, in command of German troops in the Axis Force.

One has heard odd stories about the surrender; for instance that when the occasional German or Italian did kill himself by walking onto one of his own minefields when he was trying to get into the surrender march, a high-ranking officer was reported as saying, “Good. Drive as many as you can onto the minefields.” As far as I was concerned, or anyone else in the reception party with whom I then or later spoke, there was no evidence whatever that the surrendering officers and men of the Axis Forces were treated with anything but kindness and complete lack of animosity or vindictiveness. Rather, men limping with wounds or any other sort of distress, were gently escorted away to field ambulance units for attention.”

Peter Hughes D’Aeth also watched the thousands of Germans and Italians coming down from the hills, posted with his section of carriers at a ‘T’ junction near the town of Enfidaville. He was approached by several Germans and asked which way they should go. His reply was that if they wished to go with the Eighth Army they should turn right at the junction, or take the left turn if they wished to go to the First Army POW cage. Invariably their reaction was “We have fought the Eighth Army all the way. We will give ourselves up to them.” What Capt Hughes D’Aeth did not point out to them was that they had chosen bullybeef and Victory ‘V’ cigarettes, but had they gone the other way it could be Compo, English cigarettes and a NAAFI!

Next day 169 Brigade moved back some two miles to a concentration area where they spent a couple of days clearing the battlefield of the prodigious quantities of equipment the Germans and Italians had left behind. The Signals and MT Platoons found many useful spare parts, and these, together with certain enemy small arms, the battalions were allowed to keep. Then, preceded by the 2/5th Queen’s, the Brigade moved to an area about 6 miles north of Sousse in order to provide guards on POW cages. The prisoners had been marched down from Enfidaville, the Germans smart, clean, marching in formation and singing the ‘Horst Wessel’ song, but the Italians slouching in a dispirited manner, begging for ‘Acqua’. It was noticeable that there was little love lost between these so-called allies, and they had to be strictly segregated into separate camps. The Brigade’s duties were far from arduous, since the camp was only a few hundred yards from the sea, and much of the time was spent bathing. On the 25th May the Brigade began moving in easy stages back to Tripoli.

169 Brigade were sent to a bivouac area some five miles to the east of Tripoli in olive groves about a mile from the sea. Flies were plentiful by day and the mosquitoes took over from them by night. 131 Brigade had beaten them to it. They were about 45 miles further east, bivouacked on the sand between the palm groves and the sea near the ruins of Leptis Magna, with its superb Roman amphitheatre built by Septimus Severus. By any standard, this was a marvellous camp site with superb bathing from the limitless golden sandy beaches. Homs was close by and accessible to both the brigades. But here again the Desert Rats had got there first and the NAAFI was called ‘The Jerboa Club’; but then rank always did have its privileges! One thing they had in common. The water was rationed to one gallon per man per day. They were all firmly back with the Eighth Army, and the luxuries of the First Army were but a dream.

Major-General G. W. E. J. Erskine taking the salute

as the Anti-Tank Platoon of 1/7th Queen's drives past, June 1943.

Major-General Erskine presenting the Military Medal to Sgt J. Stewart,

1/7th Queen's, June 1943.

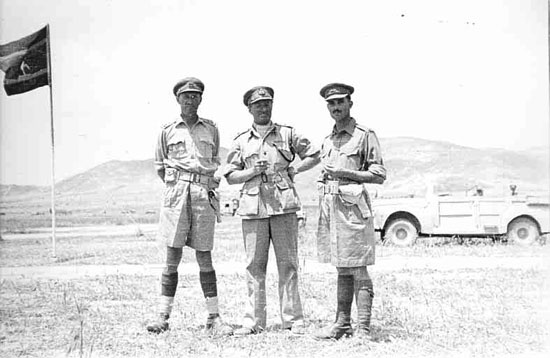

L-R Brigadier 'Bolo' Whistler, DSO, Major-General 'Robbie' Erskine, GOC 7 Armed Div,

Lieutenant Colonel Desmond Gordon, DSO, CO

1/7th Queen's at Homs, June 1943.

« Previous ![]() Back to List

Back to List ![]() Next »

Next »

Related