The Capture of Khelat

The only other encounter of the 1839 campaign, and one in which the Queen’s were heavily involved, was at Khelat, a fortress town some 100 miles south of Quetta. Shortly after the Bombay Division arrived back in Quetta, news was received that Khelat had been occupied by an Afghan force which was then in a position to threaten the communications between Sind and Afghanistan.

After the Afghan commander, Mehra Khan, had rejected liberal terms to persuade him to surrender, a force was despatched to make him do so. It consisted of the Queen’s, the 17th Foot and the 31st Bengal Native Infantry supported by six pounder guns of the Bombay Horse Artillery and two nine inch howitzers from the Shah’s troops. Major-General Willshire decided to command it himself.

The approach march was a cautious one through mountainous country. For three days before reaching Khelat the column marched in order of battle protected by its skirmishers, and at night strong pickets were posted and the soldiers slept with their arms, ready to fall-in at a moment’s notice. The town with its citadel, surrounding walls, and outlying gardens came into sight at eight o’clock in the morning. Skirmishers of the leading light companies occupied the gardens; the artillery was brought into action to dispose of threatening enemy horsemen, who retired precipitately and were seen no more; and Major-General Willshire rode forward with his engineer officer to make his reconnaissance.

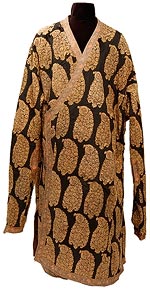

| (Click to enlarge) The Coat of Mehra Khan of Khelat |

|

The sword which belonged to his

Shakyasee, or his Adjutant General. |

The town, dominated by the citadel, resembled Ghuznee but on a smaller scale and, as at Ghuznee, it was necessary to secure by a right flanking movement the nearby high ground from which to direct covering fire for the assault. But this was to be a rapid daytime attack, and the guns were to be used to demolish the main gate from which the assault parties were to gain admission to the town and fight their way through the narrow streets and alleys to the citadel. Three columns, each of four companies from the three regiments, secured the high ground after an artillery bombardment. The Afghans retreated to the town and abandoned several of their guns. The Queen’s and part of the 17th then mounted a frontal attack from the north while the rest of the 17th and the 31st Bengal Native Infantry gained entry from the east. Part of the reserve moved around the west side to secure the heights to the south in order to intercept any of the garrison attempting to escape in that direction. The manoeuvres have a modern ring but the distances were much tighter and the formations were much closer, aspects which are well depicted by a contemporary print showing the scene as the Queen’s formed up for their assault.

The Queen’s, urged on by Major-General Willshire, charged the main gate to secure entry while it remained open to receive enemy retreating from the high ground, but it was shut before they could get there and guns had to be brought up to within 150 yards in order to knock it down. Eventually the citadel was taken. Mehra Khan died fighting gallantly and by late afternoon the fighting in the town was over as the few desperate men who still held out were persuaded to give themselves up on the promise of their lives being spared. Mehra Khan had managed to send away all his harem and family on the morning of the battle but most of the other chiefs, not being so fortunate, deliberately cut the throats of all the females belonging to them when the fortress fell rather than allow them to be taken with it.

Mehra Khan had 2000 men under his command; some escaped, others were killed or wounded, and many were taken prisoner. General Willshire’s force lost 138 killed and wounded of which a quarter were from the Queen’s. Among the Queen’s officers severely wounded were Lieutenant Holdsworth and the Adjutant, Lieutenant Simmons. It had been a highly successful action against an enemy superior in numbers and one which reflected great credit on all the regiments involved.

Back at Kabul, Dost Mohammed surrendered to the British envoy, Sir William McNaughton, and was sent to live in India with a substantial pension. A cantonment was set up near the city. It was not in a good position for defence, but there was room for a race course and a polo ground and the English officers settled down to garrison life. The band played in the evenings and there were balls, dinner parties, and whist in the mess and at the club. But it was unsafe to go on shooting parties, which were apt to be cut off, murdered and mutilated. One officer said later - “I have seen things in a man’s mouth which were never intended by nature to occupy such a position.” Continued revolts and the threats of revolts necessitated the retention of garrisons at Kabul, Kandahar, Ghuznee, Jelalabad and elsewhere which, together with much expenditure on allowances to tribal chiefs, kept an uneasy peace.

Related