Life For The Families - Young Domoney

|

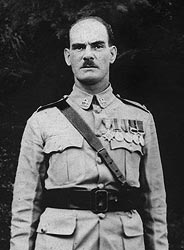

| RSM AJ Domoney

2nd Bn The Queen's Royal Regiment. (Click to enlarge) |

There was much separation. The husband was frequently away from station on duty, and in the hot weather all families were required to go to the hills, whereas perhaps only half or two thirds of the battalion might be spared to go there. However the quarters were an integral part of the station and the families were much involved in the life of the unit. The Sergeants Mess Notes of 1st Queen’s recorded, for example, in the May 1937 Regimental Journal that:

“The Ladies Rifle Club has been revived and is proving very popular. There has been some extremely good shooting of which the competitors are very proud. It is rumoured that pictures have been taken down in some quarters, and used targets displaying the householder’s skill substituted. It has been very clearly demonstrated that the staff at Hythe and Pachmarhi (musketry schools) could pick up a few tips, as we find that it is absolutely essential to lie in a perfect curve behind the rifle to get good results, and silence on the part of waiting competitors near the firing point is not only ridiculous but unobtainable.”

The Royal Army Education Corps warrant officer responsible for teaching soldiers also ran the school for the children of the unit families, and the military hospital had special facilities for families.

|

| Families shopping for brass ornaments in the market. (Click to enlarge) |

Major A M V Domoney has recorded his childhood memories of the early 1920s. His father, then a Company Sergeant Major with 2nd Queen’s, had sent for his family in 1920 after families were permitted to join the battalion. There were not many of them as the qualifying age for quarters was twenty six for soldiers and thirty for officers. When they arrived at Rawalpindi he was away on the North West Frontier. They lived in tented accommodation which they shared with the family of RQMS Shales. On one occasion when tribesmen attacked the camp the Shales’s daughter, aged nine, drove off a Mahsud with her slipper when he tried to enter their tent. The children attended school some distance away. One day they were caught in a sandstorm and had to take refuge in some ruins until found by a search party.

Young Domoney’s father had a pet monkey. One morning, at about 6am he heard his father shouting “Has anyone seen my teeth?” They were found with the monkey who was trying to get them into his mouth. That monkey was not at home when they returned from school.

The families moved to a hill station for the hot weather. Major Domoney recalled that:

“The journey was a nightmare; the first part was by road transport followed by about four hours by dandy (a seat carried by four stalwart hill men). Sometimes we appeared to be in the clouds. Our accommodation was not tented. We had an upper storey quarter with a verandah. On one occasion a brown Himalayan bear tried to enter our quarters by the door. The door was strong enough to keep him out and he was shot early next morning by one of the officers.

|

| CSM Domoney and family. (Click to enlarge) |

The quarter was heated by log fires; woodcutters would bring large logs by pack transport to the quarters and cut them up into kindling wood. These wood-cutters were sturdy hillmen. One cut his leg badly and my mother rendered first aid. He was most grateful and brought her huge bunches of dahlias and rhododendrons next day.

Water was brought round in skins by the bhisti, (water carrier). One of these had known my father on the Frontier and wherever we were in India he seemed to turn up. Milk was brought round in large cans by the dudh wallah, after it had been tested by the health authorities. Rations were delivered by the ration corporal. There were no shops but the native bazaar at Barian was some miles away. There was a hill greengrocer who called at the quarters. We could pick peaches, apricots and lychees growing wild on the hillside. We walked to school past trees where monkeys abounded and they often threw fir cones at us. The mother monkey, with offspring on her back, used to climb up to our verandah and beg for food”.

In September 1921 we moved to Lucknow. The married quarters were in a block of six. The children did a lot of kite flying: Powdered glass was glued to the string which enabled us to cut the others’ string in kite fights. We also played with yo yos and gambled with marbles.

Schooling was rather haphazard; we never went to the same school for more than four months. It all depended on the availability of Regimental Instructors and on rare occasions on Army School mistresses. But we learned our 3 Rs and were well versed in Military and Empire history.

Two of the sergeants had a tame mongoose, and if any of the quarters were invaded by a snake, Rikki Tikki soon sorted it out. These same men taught me to darn, much to my mother’s delight. For ever after it was my job to darn the socks and stockings.

We visited several well known places - I can remember the Jumna Bridge and Palace of Lights - the fabulous furniture, miniature mosques and the Palace lit by thousands of electric lights; how different from our quarters in the hill station lit by hurricane lamp.

Family routine was governed by the bugle calls. Reveille 0500hrs, Father gets up; we all get up. We stood to attention for “Retreat”, and at “Lights Out” our electricity was switched off. Meals were taken when father was not on parade. Even our parrot could imitate some of the bugle calls.

The dhobi would wash my clothes and return them ready to wear the same day. I would change three times a day just leaving them for the bearer to pick up off the floor! Another visitor to the verandah was the darzi, the tailor. He would arrive with a bundle of cloth and an old Singer sewing machine perched on his head. He would make anything required.There was an old blind Indian who visited the quarters. He had a one-stringed fiddle made from a Huntley and Palmer biscuit tin with a piano wire for the string and the fret was bound by rubber washers from lemonade bottles. The soldiers had taught him a number of risque songs and he always finished his repertoire by singing “Poor blind Charlie”. The song went “Chase me Charlie, chase me Charlie, up the leg of me drawers!” He was scrupulously clean and honest and seemed to make a living.

The Band and Drums would give recitals on the parade ground for the troops in barracks. Each night there was a film show in the gymnasium. They were of course silent films, and one could hear the silent munch of roasted peanuts purchased from the Indian vendor at the door. And the floor would be covered with husks. There were weekly dances in the Sergeants’ Mess. Teenage girls were strictly chaperoned. Fraternising with the Indians and Anglo-Indians was not encouraged.

And so life went on. My father was the warrant officer of the guard for the Prince of Wales when he toured India and was presented with a silk sash by the Prince. At the Ranikhet Hill Station he was appointed acting RSM, and he organised a social life for the detachment - sports, dances, gymkhanas and picnics. The school, where there was an Army schoolmistress, was about half a mile from the married quarters. One morning on our way to school we came across a donkey that had been killed and half eaten by a leopard. The local British representative and some officers organised a hunt, tracked the animal for two days and eventually killed it some twenty miles away. At Ranikhet we acquired a white Persian cat which remained with us for five years before being stolen.

The whole family was invited to tiffin with the British representative. This meant clean clothes, well washed, hair brushed and put on our best behaviour. The British Raj was very much in evidence; uniformed servants, silver plate and beautiful china. No sooner had you put your knife and fork down on the plate than it was whisked away, and Mother wasn’t used to having her chair moved for her. The meal was cucumber soup, curry with all the appropriate fruits, rice and sauces, followed by a very sweet pudding. We apparently did not disgrace ourselves as we were invited again.”

The Domoneys left India with the battalion in 1926. They sailed from Bombay in HMT Assaye. He and his father: “had a First Class cabin which entitled us to fruit and biscuits with our early morning tea. We of course met up with the family during the day. Spaces were reserved on the poop deck for animals being brought home. We had two parrots. It became my sister’s job to feed them.”

2nd Queen’s were bound for Khartoum where there were no married quarters. Families therefore remained on board when the battalion disembarked at Port Sudan. They went on to England and CSM Domoney, who was due for discharge on completion of his service went with them.

Related