Razmak

|

| Mahsuds (Click to enlarge) |

Early in 1940 1st Queen’s were warned for duty on the North West Frontier. A team of officers and NCOs spent a fortnight under instruction in the Khyber Pass area. There then followed six months of intensive training at Allahabad getting fit and rehearsing frontier warfare drills. In October the Battalion moved to Razmak in Waziristan 7,000 feet up in the hills on the border between the Wazirs and the Mahsuds, where there was a garrison of one British and five Indian battalions, and where the Faqir of Ipi was again fomenting trouble. For the next twelve months it was deployed on active operations with the Razmak column in both South Waziristan and on road picquets between Razmak and Bannu.

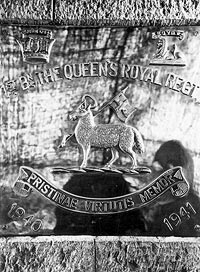

|

| Cap badges in stone - 1903 - 1941, Khyber Pass. (Click to enlarge) |

The situation there had changed little over the previous years, especially the nature of the tribesmen and the picquet drills employed by troops on escort duty. Major A.R.C. Mott, who was in command of D Company, 1st Queen’s, at the time, has described their experiences:-

“There were six battalions in Razmak and we were the only British one among two Gurkha battalions and three of the Indian Army, and of course supporting arms and services, all Indian. Razmak was known as the largest monastery in the world, not because of piety, but because there were no women allowed there.

In addition to the Regular Army garrisons there was a chain of posts manned by Scouts who were Pathans from other areas, trained and led by officers of the Indian Army. They were very fit, mobile and self-supporting in the field, but somewhat vulnerable in so far as a ‘lashkar’ (irregular force) of Pathans could cut off a Scouts’ post if it were isolated.

|

| The Guardsroom, North West Frontier. (Click to enlarge) |

The opposition was potentially any of the local inhabitants. They lived in villages with formidable walls and observation towers: they cultivated and were herdsmen. When we were there the Faqir of Ipi was the big shot on the other side, and if he decided to assemble a lashkar to surround a Scouts post or cause general mayhem, several hundred Pathans would rally to the cause. But day by day there was the danger that half a dozen Pathans, who were watching our every movement, would note some slackness or regular method of carrying out some task, lie invisible in ambush, fire a volley from close range and attack the bewildered party with knives and be off with rifles, ammunition and their victims genitals before any support or relief could be laid on to help our soldiers.

|

| The parade ground, Lucknow. (Click to enlarge) |

As a result, whatever we were doing we had to protect ourselves. Razmak had a perimeter wall and fence, but was also surrounded with permanent camp piquets, fortified and about half a mile from the perimeter. Twice a week the road to Bannu was opened and lorries left Razmak empty and others came up with fresh supplies. But before this could start two battalions with supporting arms moved astride the road, sending piquets of about a platoon up to features overlooking the road, and there they would stay until the last vehicle had passed and the piquets were recalled. We were responsible for five or six miles of road and beyond that piquets were provided from the other garrisons. It could be monotonous work and the weather varied from snow - Razmak was 6,000 feet above sea level - to blazing heat, butevery time a piquet was sent up, the commander made a plan of support, and variation from last time. Supporting gunners and machine guns were ready in the column.

Usually one paused below the crest, charged the top and occupied the sangar (stone walled perimeter) on the alert until recalled. Signalling was by flag. ‘I P A’ (I am in position) was reported and the column moved slowly on. The return journey was more hazardous. Pathans could be hidden within 50 yards of the piquet and perhaps not many hours of daylight were left. Fighting in the dark had to be avoided if possible. So usually the piquet commander would thin out when withdrawal seemed imminent. The ‘R T R’ order to withdraw was acknowledged, and the remaining section had to be out of the sangar and down to the rest of the piquet in a flash. Then altogether back to the column at best speed, someone in the last wave wearing an orange screen which showed supporting arms that all was clear behind him. And if our opponents inflicted a casualty on the way down, the piquet commander had to retake the position immediately and stay until the casualty had been evacuated. No dead or wounded person was allowed to fall into the Pathans’ hands.

|

| (Click to enlarge) |

Our dress for the winter operations was a balaclava helmet, shirt and sweater, trousers, long puttees and boots. Leather jerkins were issued and for camp life my Gilgit boots, quilted, wool-lined and coming above the knees were invaluable. Normal training took place as far as possible, and there were sports grounds, some of them outside the perimeter. For officers there was a good club where we could meet our fellow ‘monks’ and hospitality in asking our friends to our Mess or going to theirs.

This was in the days before mepacrine and paludrine and our only defence against malaria was quinine, which was only a suppressive. As a result malaria became rife in the battalion and at any time a considerable percentage of men suffered from malaria or relapses for years afterwards. I have always had a theory that whisky was an excellent preventative against malaria - at any rate the whisky drinkers - CO, 2nd in Command, Quartermaster, myself and one or two others never suffered, nor did any of the doctors who carried ‘medicinal’ spirits among the more generally accepted pills and potions.”

|

| Group of tribesmen, Waziristan, 1921.. (Click to enlarge) |

On one occasion when they were out on operations during the afternoon in a cloudless sky all who could, including the Officers’ Mess, set up shop in a dry nullah bed when a thunder cloud discharged its contents on top and, wrote Major Mott, “our wiser Indian friends urged us to move from the nullah. Never has a camp been struck more quickly as a trickle became a flood, and just as the last tents and equipment were brought to the bank, a wall of water roared down the nullah bed.” On another occasion two lorries containing sailors overtook the column and, explained Major Mott, “This was a party from HMS ‘Kelvin’, a destroyer, whose stern was badly damaged off Crete and which had come to Bombay for repair. This took longer than expected and the Captain (who deservedly rose to at least Rear Admiral) decided that his men should not rot in Bombay, but should see a bit of India. The story went that by the time Their Lordships in England had answered his request in the negative, the party was out of touch in Kashmir. But we had the pleasure of entertaining the Royal Navy for a few days, and you can imagine how the ‘Excellent’ connection was exploited, if such an excuse was needed for us to have a party after all those weeks on column. And Buckshee Bill, the local sniper, entertained us all with a few rounds as we watched a garrison open-air entertainment, which was prematurely adjourned to Club, Messes and Canteens.

The Battalion was involved in two punitive operations while it was based at Razmak during which it sustained several casualties. Negotiations followed and among the punishments awarded by the Political Agent were handing in a number of rifles and destruction of towers in some Mahsud villages. A bomber came staggering along at perhaps 90 mph, dropped its load, and returned more quickly to base. There was also a Medium battery which could perform the same tasks. There was a feeling that the headmen of the destroyed villages would be given money to rebuild, but that may not have been true”.

The column returned to Razmak at the end of August 1941, and shortly afterwards 1st Queen’s moved to Ambala and Peshawar where they spent a less demanding year before moving again to the jungle country around Chinwara to prepare for the Burma campaign in which the Battalion so greatly distinguished itself and for which the foundations had been laid during that year at Razmak in the harsh school of frontier warfare.

Related