The Queen's in Afghanistan

The First Afghan War

In 1838 a Persian army laid siege to Herat, a city astride the trade route between China and the Mediterranean and the western approach to Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan. Dost Mohammed, the ruler at Kabul, sought an alliance with the British in return for which he asked for their support for the return of the Peshawar valley which had been appropriated by the Sikhs in 1826. However the newly-arrived British Governor-General, Lord Auckland, decided instead to invade Afghanistan, occupy Kabul, and place a rival contender on the Afghan throne. He was Shah Shuja, who had sought refuge in India after failing to gain power in Kabul and had become a British pensioner.

|

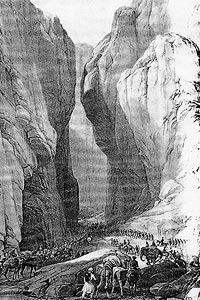

| Army of the Indus enters Bolon Pass during invasion of Afghanistan 1839. (National Army Museum). (Click to enlarge) |

The British Commander-in-Chief’s considerable reservations about supporting a sufficiently large force in such distant and hostile territory were overruled. Suspicion about Russian intentions in support of the Persians prevailed and preparations went ahead despite the withdrawal of the Persians from Herat in September 1838. The invading force became known as the Army of the Indus. Its main component, some 20,000 troops, was to be provided by the Bengal Army. The Bombay Army was to contribute a smaller number, to be known as the Bombay Division, consisting of two brigades one of which was made up of the Queen’s, the 5th Native Infantry and the 1st Grenadier Native Infantry. The regiments from the Bombay Army were to proceed by sea to the mouth of the River Indus, disembark and approach along the north side of the river to link up with the Bengal force at Larkhana. From there the Army of the Indus would advance on Kabul by way of Quetta and Kandahar.

The Queen’s had been sent to Belgaum in the south of the Bombay Presidency in 1837 where they were operationally deployed. When orders were received for Afghanistan outlying columns were hurriedly withdrawn and preparations began for the ten day march to the port at Vingorla where they were to embark for the Indus. Very little was known about Afghanistan except that it was a wild mountainous place inhabited by ferocious tribesmen. Few of the Queen’s soldiers had experienced action before, and that in the final stages of the Napoleonic War. None of the officers had been in action except their commanding officer, Brevet Colonel Baumgardt. He had recently returned from leave in England. He had campaigned with the 56th Foot in South Africa in 1798, and in India in 1803-7 and during the 1817-18 Maharatta Wars with the 91st Foot. He had become a lieutenant -colonel by purchase to the 31st Regiment and exchanged to the Queen’s. His predecessor in command of the Queen’s, Brevet Colonel Willshire, had been commanding the Poona Brigade and was now appointed to command the 1st Brigade of the Bombay Division of which the Queen’s were to be part.

Apart from their fifty-two year old commanding officer the rest of the Queen’s officers were young. The lieutenants were in their twenties and the captains in their thirties. The only exception was the sixty-nine year old paymaster, Lieutenant John Darby from Dublin, who was commissioned into the 8th Light Dragoons in 1806 and exchanged to the Queen’s in 1824. Sadly he died at Bombay on his way back to the regimental depot which was being formed at Poona to look after families and receive reinforcement drafts.

The Queen’s embarked at Vengorla on 1st March 1838. They transhipped at Bombay into a sloop belonging to the East India Company and a chartered Swedish ship. They arrived at Hujamri at the mouth of the Indus sixty miles south east of Karachi, where the Bombay Division was assembling, on 26th November, and set up camp while contractors and pack animals were engaged. The approach march to link up with the Bengal force began, at last, on 26th December.

The nights were cold and the days were hot. The packs containing the soldiers’ personal possessions were carried on the baggage carts, but each man was required to carry a blanket with a second shirt, stockings and his flannel waistcoat wrapped in it so that they could change as soon as they completed the day’s march. The weight of this, together with weapons and equipment, 20 rounds of ammunition, the day’s rations and a small keg containing water was no small burden for the soldiers to carry in the heavy going. There was little water away from the river except in stagnant pools and there were a number of cases of cholera. There was also a constant threat from hostile tribesmen. Nevertheless at the halts officers would often form shooting parties to go after whatever game was to be found in the vicinity and provide fresh meat. One such occasion led to tragedy when three young officers -Lieutenants Sparks and Nixon and Assistant-Surgeon Hibbert -were cut off by a sudden bush fire and burnt to death.

News was received on 5th February that Admiral Maitland in the 74 gun ship Wellesley had bombarded the fort at Karachi and reduced it to ruins. The Baluchis manning it had presumed to open fire as he arrived with the 40th Regiment. The Sind Ameers who had been reported to be assembling an army of Baluchi tribesmen to resist the invasion were much impressed and as word spread the risk for stragglers and shooting parties was greatly reduced. An immediate consequence was that the Queen’s officers were able to cross the river and visit the city of Haidarabad, a courtesy which was returned by the Ameer.

The march was resumed on 10th February after the pioneers had cleared a road for the artillery through the Lukhi Pass across a mountain spur which ran down to the Indus. A regiment of light cavalry arrived from Cutch and was deployed in front of the column. They were a fine looking body of men dressed in green hussar uniforms edged with gold braid, and with a few European officers. Larkhana was reached on 4th March when a number of changes in command occurred. Among them Major General Willshire was appointed to command the Bombay Division and Colonel Baumgardt was promoted to command the 1st Brigade in his place. Major Richard Carruthers received the brevet rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and became the new commanding officer of the Queen’s. Born in 1799, he had been one of the first graduates from the new Royal Military College at Sandhurst. He was commissioned by purchase into the 26th Foot in 1814, and transferred to the Queen’s to become a Lieutenant without purchase in 1836.

The two Indian regiments of the 1st Brigade remained at Larkhana to garrison the crossing point over the Indus and were replaced by H.M. 17th Foot. The route now led away from the river northwards up a broad valley towards the Bolan Pass and Kandahar, and the invasion was resumed along it on 11th March with the Bengal Division in the lead. On the 22nd a soldier of the Queen’s named Adams had fallen behind with dysentery. He was set upon by a party of Baluchis and killed, and a soldier of the 17th Regiment with him was badly wounded. A detachment of Poona horse was sent after the tribesmen and succeeded in killing eight and taking five prisoners. After discussion with the political advisers accompanying the force it was considered expedient to release the prisoners and give them each five rupees to help them home.

Philip Mason, in his account of the Indian Army, makes use of the memoirs of one Subadar Sita Ram who was an admirer of the British but at times found their attitudes incomprehensible. This was one such occasion. He could not understand the English readiness to spare a wounded enemy. He wrote: “I have seen an officer spare the life of a wounded man who shot him in the back as he turned away. I saw another sahib spare the life of a wounded Afghan and even offer him water to drink but the man cut at him with his curved sword and lamed him for life. The wounded snake can kill as long as life remains, says the proverb, and if your enemy is not worth killing, surely he is not worth fighting against.”

Private Wilkins of the Queen’s later recorded his experiences. He wrote “The sufferings of our army at that time would be quite impossible to pen. We had to convey water from one camp ground to the other on camels and buffaloes under a strong guard, and when we arrived it was served out to the soldiers the same as spirits, and to augment our sufferings one was on half rations - not one drop of grog to cheer our drooping spirits. Our supplies could not reach us owing to our rapid progress, and also our camels dying like rotten sheep from fatigue and starvation. It took us six days to clear the Bolan Pass. The scenes presented to my view summoned up my blood with horror - dead men, women and children, camels, buffaloes and horses. The smell was disgusting. The Baluchis did all they could to stop our progress - but in vain. They kept up regular fire and several narrow escapes came to notice. One man had his canteen straightened by a ball, another had the muzzle of his piece closed just as he was in the act of firing. Another found a ball in his knapsack. And many other events too tedious to mention at this time. Believe me, it was no strange thing to see a Baluchi head brought into our camp by someone of our army as a trophy.”

The Bombay Division reached Kandahar on 4th May, a week after the Bengal force. On 8th May Shah Shuja was installed as Amir at a grand parade in which the Queen’s took part. A few days later he held a levee when every officer in the force was presented to him. Each was presented with a number of gold mohurs according to his rank. Their enjoyment was not shared by the people of Kandahar. They had little respect for the Shah who had been regarded as a weak ruler in the past.