Troopships and the Regiment

Introduction

For over three hundred years Great Britain being an island of Europe, relied to a large extent on chartered ships to carry her troops overseas to meet her military commitments.

The first overseas station (apart from Dunkirk and Calais) was Tangier, and The Tangier Regiment it is recorded in the histories sailed on ‘a fleet of ships’. Most of the troops were packed in very unhygienic and generally appalling conditions.

Over the centuries thousands of soldiers were transported by literally thousands of ships. It is NOT the intention for the following notes to be regarded as the definitive answer to trooping, but a reminder to our Regiments (The Queen’s and Surreys) of some of the ships which conveyed them to far distant shores.

Towards the middle of the 19th century, steam was beginning to replace sail and the first steamship used for trooping was the Enterprise, a wooden paddle steamer of 479 tons completed in 1825.

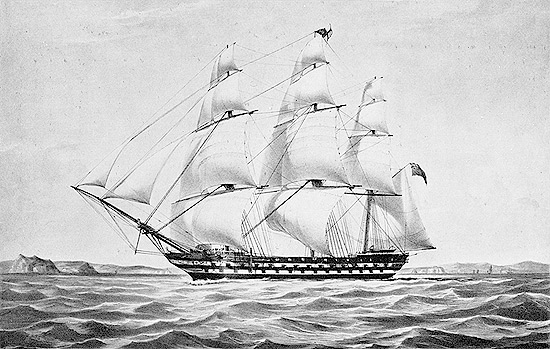

The East Indiaman - The Earl Balcarras, on early troopships.

The Boer War of 1899 to 1902 involved the transport overseas of the largest force ever to leave Britain, resulting in the Admiralty Transport Service having to draw in the ships of virtually every major shipping company.

Thus, in addition to the companies already in peacetime trooping, P&O, British India and Bibby Lines, ships were requisitioned from the Cunard, Anchor, White Star Line and Allan Lines in the early months of the campaign.

One company operating some of the troopers was the famous P&O shipping line. Established in 1835 as the Peninsular Steam Navigation Company to undertake passenger service between England and Spain, they extended their activities eastward to Egypt and India in 1837 when they took four new ships into their fleet, one of them named Braganza and described as being of 650 tons and of 250 horse power. By that time they were attracting the attention of Army Officers and their families when travelling on duty and leave. The company title was changed to the Peninsular and Orient Steam Navigation Company in 1840 on incorporation by Royal Charter.

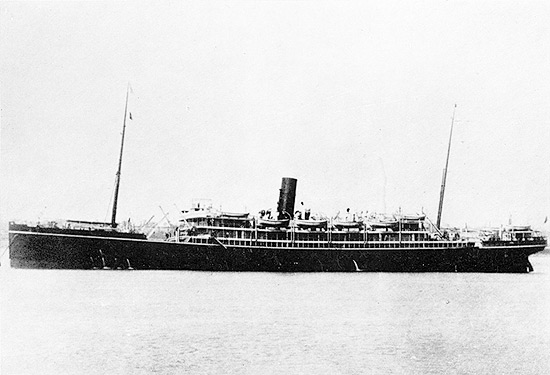

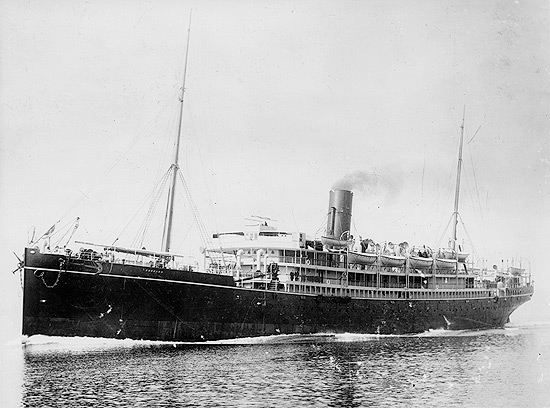

HMT Assaye

During the Boer War the P&O line built three ships specifically for trooping purposes, namely Sobraon, Assaye and Plassy. Sobraon although titled with a famous East Surrey Regiment battle honour, unfortunately had a very short career as on her third (but definitely not lucky) voyage she ran on to a reef in thick fog off the coast of China and was a total loss.

SS Sobraon

Troopships for the carriage of British troops to and from overseas garrisons had their origins in King Charles II’s reign (1660-85). One of the first regiments to be moved by ship from England to Tangiers in 1662 would have been The First Tangier Regiment which later was to become The Queen’s Royal Regiment (after many changes of title).

By the late 18th century the Honourable East India Company’s sailing ships, which were comparatively spacious with ample deck space and a useful armament for self-defence, were regarded as the best ships available for carrying troops. During the Napoleonic Wars the East Indiamen were supplemented by Royal Navy frigates of around 1,200 tons, two deck ships, carrying 40 guns on a single gun deck and with the lower deck given dummy gun ports to provide an illusion of greater fighting power than they possessed. The Crimean War of 1854 marked the move to the steam propelled troopship. In 1853 P&O had built the 3,438 ton single screw steamship Himalaya, the world’s largest steamer and almost twice the size of any other ship in their fleet, capable of 12 knots using her 2,050 ihp steam engine alone and about 16.5 knots on occasion under engine power and a full spread of sail. However she proved uneconomic for the company’s trade and was running at a loss, so an offer in 1854 from the Admiralty of £130,000, equivalent to her cost price, to buy her for service as a troopship was accepted. After the end of the Crimean War Himalaya was used for trooping voyages to India until 1894 when she was converted into a coal hulk. Sold in 1920 she met her end in June 1940 when German bombers sank her in Portland Harbour.

HMS Himalaya

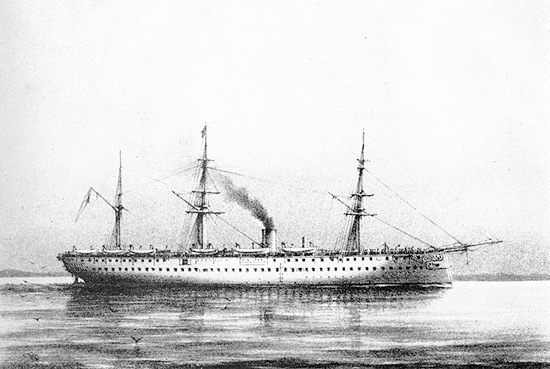

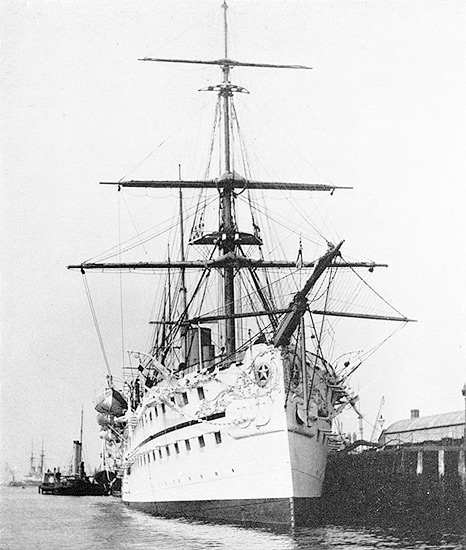

In 1863 the Royal Navy was instructed to build and operate on behalf of the Indian government five steamships specially designed for trooping. The rigged iron screw steamships Crocodile, Euphrates, Jumna, Malabar and Seraphis of 6,211 tons, 360 feet long with a 49 foot beam, were built in 1866 and served as troopships until 1894. Like later troopships they had white hulls with a blue coloured riband and yellow funnels. In 1894, instead of replacing these five troopships, which were by then worn out by nearly 30 years of service, the Admiralty invited tenders for troopships which the government could charter with the shipowners to be responsible for managing and manning the ships and for victualling them, a system which proved more economical than running government owned ships, and would continue until the troopship era ended. The ships were designed to carry a complete battalion of troops. The Indian Government paid the costs of running the service but the Royal Navy operated the ships.

HMS Crocodile

The Troopship Malabar

House of Commons (Hansard, 17th April 1890)

Questions were asked in the House concerning conditions on board HM Troopship Malabar.

HC Deb 17th April 1890 vol 343 cc687-8

Mr Munro Ferguson & c (Leith)

I beg to ask the First Lord of the Admiralty whether it is a fact that there were 14 funerals on board the Malabar troopship during her last home voyage; 688 that she carried 200 invalids at starting, and 300 by the time she reached Malta, and whether the numbers on board were in excess of Admiralty Regulations?

Lord G Hamilton

Fourteen deaths did occur on board the Malabar during her last homeward voyage. Excluding officers and ladies, 644 invalids were embarked, but the term “invalid” includes not only men in the last stages of organic disease, but also those who have ailments which render them unfit for service only, and who are otherwise in health. The numbers embarked were not in excess of those allowed by the Regulations, but the number of invalids embarked is settled by the Military Medical Authorities at Bombay, who alone would be in a position to decide upon the proportion of sick that it would be safe to embark at one time.

The Malabar was one of the Indian troopships, the others being the Jumna, Seraphis, Crocodile and the Euphrates, nicknamed the Lobsterpots. They were sister ships, barque rigged and painted white, with the Star of India in gold on either bow. They drew 22 feet. The bar at Port Said had in those days 28 feet of water, so that these ships could cross except in a rough sea. Their speed was under 9 knots. With a fair wind and under all sail, 11 knots were recorded.

Prior to the opening of the Canal (November 1869) Seraphis and Crocodile ran between England and Alexandria. The troops were carried overland to Suez and completed the voyage in Euphrates, Jumna and Malabar.

It was recorded by one officer on boarding HMS Crocodile for the first time in Quebec, “A sumptuous ship. The accommodation for officers splendid. That for the men very good. But not adapted for taking a field battery with its equipment and stores.” However, she brought home in May 1869, a field battery complete, except horses, a battery with baggage and a regiment of foot (the 30th). HMS Crocodile was popular with the men. The food was good, though she rolled abominably. HMS Jumna was a lame duck. Her engines usually gave trouble.

The worst feature of the Indian troopships was the accommodation for officers’ wives and the wives of the men. The accommodation for the latter was horrible. Quarrels between the ladies, owing to their cramped quarters, frequently enlivened the voyage. The ladies were berthed in one long cabin opening from the saloon on the port side. Next to it was the nursery, another long cabin. The ladies’ cabin was known as the Dovecot.

These ships, or some of them, were in commission before the opening of the Suez Canal, which took place in 1869; as mentioned above, HMS Crocodile went to Quebec in 1869 to bring home troops from Canada. They were in commission for over twenty years, and carried thousands of troops across the world. On the whole they were comfortable, well-found ships. The discomfort owing to over-crowding was the fault of the War Office, not the Admiralty.

Extracted from the Journals of Army Historical Research.

HMS Malabar. Note the Star of India on the bow.

Related