The Middle East

Prologue

During 1938 the Arab Revolt in the British mandated territory of Palestine reached new heights of terrorism and ferocity. For a time British administration was only effective in the cities and larger towns, and Arab control was so firm that they had even taken over local postal services and were issuing their own stamps. More ominously, they also set up their own courts and appointed judges.

|

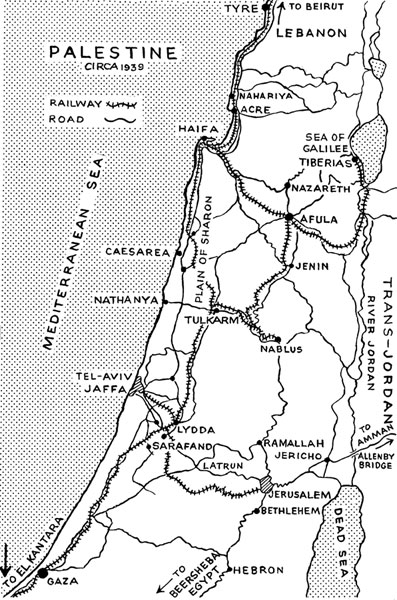

| Palestine circa 1939. (Click to Enlarge) |

The reasons for the revolt originated some 20 years previously from the Balfour Declaration, which had contained the suggestion that a Jewish homeland should be established in Palestine, although this suggestion was heavily hedged about with conditions concerning Arab rights to eventual self-government. Unfortunately this ideal had been hijacked by international political opinion regardless of the conditions, especially in the USA, and both Jewish immigration and land purchase increased alarmingly. In 1936 the Arabs decided to take the law into their own hands by civil disobedience and acts of terrorism, mostly against Jewish targets but occasionally against the police and the military. The local garrison was initially reinforced by a division from the UK, but this proved insufficient to contain the trouble, and by November 1938 the GOC Palestine and Trans-Jordan had under his command two horsed cavalry regiments and the equivalent of the infantry component of about two divisions.

2nd Queen’s had been stationed in the UK for the previous 11 years since returning from tours in India and the Sudan. They were fulfilling the traditional role of the home-based battalion of an infantry regiment, in that their main function was to furnish reinforcement drafts periodically for the overseas battalion, 1st Queen’s, who were having an eventful tour of duty in Hong Kong, Malta, China, and finally, from December 1934 onwards, in India. These drafts left 2nd Queen’s extremely weak at times, with companies almost ceasing to exist except for leaders and flags.

The Battalion was at Parkhurst, Isle of Wight, when it received orders in October 1938 to proceed to Palestine to replace The Royal Scots. It embarked in HMT Nevasa on New Year’s Eve with a strength of 23 officers and 572 other ranks at Southampton, and arrived ten days later at Haifa, to be greeted by their new divisional commander and former brigade commander, Major-General B.L. Montgomery. Disembarkation took place on the 11th January 1939. and the Battalion was immediately moved in buses escorted by armoured cars the 40 miles to their operational base at Tulkarm. The advance party had already taken over from The Royal Scots, and a detachment from 2nd Coldstream Guards temporarily held the area, handing over the billets and returning to Jerusalem on the 13th January.

Panorama of Tulkarm

Tulkarm is situated on the road from Nablus to the coast on the edge of the Plain of Sharon, with barren hills to the east and low lying, fertile plain to the west. It was then on the boundary between the Jewish and Arab spheres of influence. Nablus and Tulkarm were the base points of what had become known as “The Triangle of Terror”, the apex of the triangle being the town of Jenin, and this was considered the main hot-spot of the Arab Revolt. HQ Company, ‘B’ Company and ‘C’ Company were stationed in Tulkarm itself, whilst ‘A’ Company was based some nine miles to the north in Baqa al Gharbiya, with ‘D’ Company about 10 miles south at Qalqilya. One platoon of ‘A’ Company was detached at Deir al Ghusun. The rifle companies were known by codenames, with ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies called “Roycol” and “Fancol” respectively; ‘A’ Company was “Budget,” with its detached platoon “Ghudet”; whilst ‘D’ Company was “Qaldet”. One platoon of ‘D’ Company fulfilled the role of Ration Platoon for the Battalion, although this did not excuse them entirely from more active duties.

|

| 14 Inf Bde's Op Area. (Click to Enlarge) |

Work started at once, mostly by carrying out cordon check and search operations or raids on specified villages or houses. When a cordon was required around a village at least a company was employed, or maybe as many as two companies plus other detachments. Tactics later became more sophisticated with up to four columns approaching the objective from different directions, thus reducing the time to totally surround a village. The soldiers named the rebels “oozlebarts”, or “oozles” for short. Operational dress were sets of overalls made up from the canvas jackets and trousers then used for fatigue work sewn together, known by the troops as “oozleing suits”. Through previous wear and laundering the jackets and trousers were invariably different shades of brown or off-white, which gave to a body of troops a somewhat skewbald appearance. Nevertheless they were a very practical form of dress.

A typical cordon check and search operation would be planned on information received from the police or from informers through brigade intelligence, and started as a night operation. A conference would be held at about 5pm and the method of tackling the village decided, after which those involved would snatch a hasty supper and go to bed. Reveille would be any time between 10pm to 2am dependent on the distance to the objective. The columns then piled into their lorries and moved out without lights. On reaching the RV the columns would halt and debus, leave the road and proceed on foot through the hills along straggling pathways and up dry wadi beds. After anything up to four hours on the approach march the village would be seen on the skyline, and the columns would split and circle the village through the olive groves as quickly and quietly as possible. Invariably by this time the dogs would be barking madly as the cordon was completed, and if there were any rebels in the village they would now either hide or make a dash for freedom, in which case, on meeting the encircling cordon, they would be shot. If there was no movement the troops settled down and waited for dawn, a cold experience often accompanied by rain at this time of the year. Just after dawn a Verey light would be fired, and the Commanding Officer, or the senior officer present, together with the Adjutant or Intelligence Officer, would go into the village protected by an escort from the Drums. At the same time the cordon would thin out, and men with Bren guns would be posted on the roofs of outlying houses facing outwards to prevent anyone breaking from the village. The CO would summon the Mukhtar, or headman, and order him to collect all the men of the village at the threshing floor, and send all the women to the Mosque. Sometimes this had been done so often that the inhabitants knew the procedure by heart. A sergeant of the Palestine Police would then join the CO’s group, somebody would bring coffee, tables and chairs, and the check of the men in the village would proceed, whilst the troops that had come in from the cordon would begin to search the village for hidden “oozles”, arms or ammunition. Finally, when all the interviewing and searching were finished, any finds or suspects would be handed over to the IO and the Drums escort, and the columns would march back to their transport if it had not been possible to drive this up to the village. Sometimes the columns would come under fire from snipers, particularly during the withdrawal phase. During the first twenty days in Palestine the Battalion carried out fourteen of such checks without suffering any casualties.

For the Motor Transport Platoon the driving conditions during such operations were atrocious, particularly in the first few months of winter and early spring when tracks could become axle deep in mud. Gradients could be terrifyingly steep, since most of the villages were situated on the top of the most rugged hills. Pte H. 'Tommy' Atkins recalls one incident when his passengers preferred to abandon his vehicle rather than face an unpleasant looking descent after an operation:

Cpl H. Atkins, MT Cpl.

“I was driving a six-wheeled 30cwt CDF lorry with the Cook Sergeant and the company cooks aboard, and had approached the village high up in the hills without lights in darkness. Next morning after breakfast the lorry was reloaded and the cooks hopped into the back and the Cook Sergeant jumped into the passenger seat. I started to move off when the Cook Sergeant yelled ‘Stop! Where are you going?’ I pointed out that the way out was down the steep slope in front onto the track, which ran at right angles to the slope, with a precipitous drop on the far side into the valley below. He got out of the lorry, ordered his cooks out, and then said ‘Bugger off Atkins! I will join you if and when you are safely on the bloody track, and not before’.”

The most successful check and search operation was carried out on the 4th-5th March as part of a double operation on the villages of Kafr Rumman and Bal’a. ‘B’ Company, less 11 Platoon, were led to a house near Bal’a by a British police sergeant, whilst ‘C’ Company plus 11 Platoon and ‘D’ Company went to Kafr Rumman during the afternoon. A wedding was in progress at Kafr Rumman, which was brusquely interrupted as the bridegroom was involved in the subsequent check of the men of the village, conducted by ‘C’ Company. 11 Platoon, who were carrying out the search, soon found five rifles and 796 rounds of small arms ammunition which had been hurriedly hidden by the shaft of an olive press in a cave. Meanwhile ‘D’ Company had been carrying out a drive on the north side, and at about 3.30pm arrived in, bringing ten suspects. Two of these were subsequently identified as sub-leaders of a local gang. In Bal’a, which had a notorious reputation, ‘B’ Company had found four rifles by sunset, but there were strong suspicions that more weapons were about. As a result permission was granted to stay on overnight. The weather was terrible with high winds and torrents of rain, and the cold was intense since the village was over 1200 feet high. There was no sleep for anyone despite the Ration Platoon bringing up a rum ration and greatcoats.

At 6.30am on Sunday, 5th March, 11 Platoon left for Bal’a with rations for ‘B’ Company. It was still raining. ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies followed at 8.30am together with Battalion Headquarters. Because of the terrible state of the track up to Bal’a the first column did not reach ‘B’ Company until 11am. However, searches continued and eventually a total of 12 rifles, a shotgun, 2213 rounds of SAA, a landmine, 9000 grammes of dynamite and several items of uniform and documents were recovered. It appeared that the Battalion had stumbled upon the local rebels’ quartermaster’s stores, and the two storemen were taken into custody. The weather conditions steadily got worse with visibility down to 50 yards as low cloud covered the hill, so the Commanding Officer called off the search at 3pm. This haul constituted a Brigade record for rifle finds, and messages of appreciation were received from Force HQ, the Divisional Commander and the Brigadier.

Another check and search carried out on the village of Anabta illustrates the increased sophistication and cunning developed in the tactics employed by the Battalion. On the 4th April information was received about a hoard of rifles. Before dawn on the 5th April ‘D’ Company, plus one platoon of ‘C’ Company, drove right through Anabta, which is situated on the main road to Nablus, with lights on and giving the appearance of rushing to Nablus. Just short of Nablus the convoy turned round and came slowly back without lights, debussing one and a half miles from the objective. Meanwhile the rest of the force had left Tulkarm in MT without lights and debussed at ‘Windy Corner’ about a mile on the Tulkarm side of Anabta. Both columns advanced on a timed basis and cordoned the village from east and west. This was done so quietly in PT shoes that hardly a dog barked and the village was completely surprised. Eleven rifles and 490 rounds of SAA were found, with 22 suspects detained, including the informer!

Windy Corner, 1939.

|

| The enemy, 1939. |

On the 23rd April ‘B’ Company took over as ‘Qaldet’ and ‘D’ Company was disbanded because a draft required for India was formed into a composite company. This draft of 119 men eventually left on the 4th May. A reinforcement draft of one sergeant and 40 men arrived from UK on the 1st May, but the Battalion continued operations with only three rifle companies.

During this period a second Royal Commission, chaired by Malcolm Macdonald, the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs and later to be Health Minister in Winston Churchill’s War Cabinet, was formulating proposals for the future of Palestine. The first such Commission had recommended partition in order to establish a Jewish homeland. However this had been one of the main causes of the Arab Revolt. In contrast Malcolm Macdonald’s team found in favour of the Arabs, proposing a halt to Jewish and foreign land purchase and the limiting of Jewish immigration to 15,000 per year for the following 5 years. The White Paper was published in Palestine on the 17th May, and, through unlucky circumstances, led to the first casualties in action suffered by 2nd Queen’s.

On the 19th May 2/Lt G.G. Reinhold took a patrol from ‘C’ Company to Qaffin in order to deliver a copy of the White Paper to that village. On his arrival 2/Lt Reinhold sent one section to the south of the village, and left another section at the north end. The northern section saw five men run across the wadi on their side of Qaffin and opened fire on them. 2/Lt Reinhold ran up with platoon headquarters, left a Bren gunner to give covering fire, and immediately gave chase. On emerging from the olive trees into the open he was heavily fired on from the north-east by about twelve other men, who were covered from the view of the Bren gunner by the shoulder of a hill. 2/Lt Reinhold was wounded whilst he was moving back to the section, who had gone to ground. Owing to his exposed position, and knowing that he was outnumbered, he ordered a withdrawal to the west of Qaffin. During this withdrawal Sgt G. Golding was also hit. On receipt of this news the remainder of ‘C’ Company rushed to the village and searched it, detaining eleven men. Whether the White Paper was ever delivered to the Mukhtar of Qaffin is not recorded!

Immediately following the Qaffin incident the Battalion carried out an unusual and probably the most dramatic operation of their tour during the Arab Revolt. In effect the operation developed into a battalion attack, using the equivalent of two weak companies, on a strongly held rebel defensive position in the area of a hill feature known as Khirbet Wasil. The Battalion returned to barracks at 12.30pm on the 23rd May to be greeted with the information about this rebel force from an informant who probably wished to curry favour with the security forces, but thought that his information could not be acted upon in the time available because of the rebels’ intention to move on next day. Furthermore the position could not be sealed off on the eastern side because of the lack of tracks and the wild nature of the country. The Commanding Officer, Lt Col R.K. Ross, DSO, MC, quickly realised that the only chance of bringing the rebels into action was to move that afternoon straight towards the position from the west and the south without regard to concealment, whilst requesting the RAF to pin the rebels down on the eastern side, which was barren and open ground. Considering the short time available and the difficulties of communications, the attack was excellently co•ordinated. Unfortunately the Battalion had only about 70 men available from ‘A’ Company, 40 men of ‘C’ Company, a reinforced Ration Platoon of 40, and the Battalion Headquarters of about 10 men.

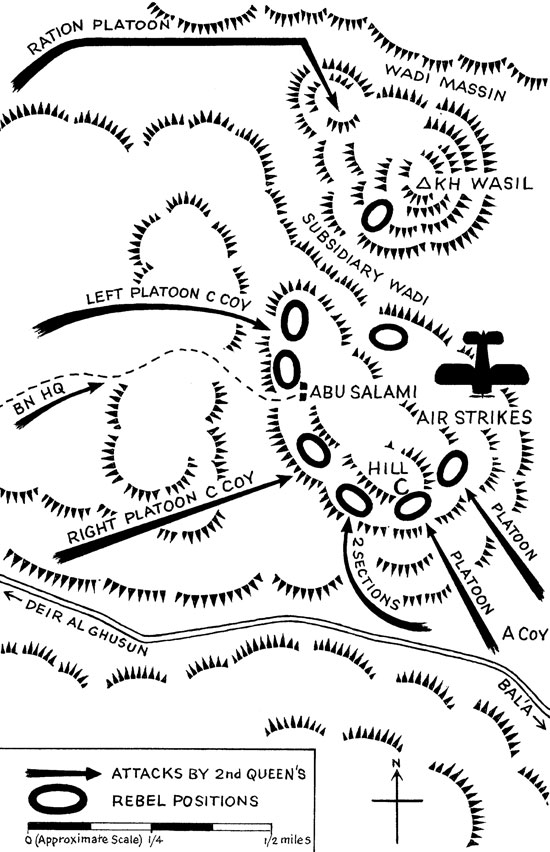

The Operations at Abu Salami - 23 May 1939.

The RAF began their airstrikes exactly on time at 3.30pm. The Ration Platoon, under 2/Lt C.E.W. Hull, on the left, moved against the rebels’ northern flank; ‘C’ Company moved straight towards the heights on which the hamlet of Abu Salami stood with Battalion Headquarters behind them on the track leading to Abu Salami; while ‘A’ Company came up from the south-east with the intention of working round the rebels’ southern positions. Not unnaturally an extremely confused fire-fight developed. Major W.G.R. Beeton, the Company Commander of ‘C’ Company, directed the advance of his company over a very exposed hillside for some 600 yards, but was killed by short range fire on entering the olive groves near the crest, where many of the enemy were firing from the sitting position with branches from the trees tied down to their ankles for camouflage. The Battalion Headquarters’ interpreter was also killed, but the Adjutant, Capt M.F.S. Sydenham-Clarke, located the sniper responsible and after an exchange of fire killed him at close range. 2/Lt Hull, on his own initiative, changed his direction of advance when he realised that the RAF were engaging targets further to the south than had been anticipated, and then occupied a hill from which he could look directly at Khirbet Wasil across a saddle. From this position the Ration Platoon accounted for at least three rebels, but came under heavy fire themselves. Both platoons of ‘A’ Company encountered heavy fire during their advance and several rebels were killed as the company tried to turn the rebel flank. Eventually ‘C’ Company occupied Abu Salami and were joined by Battalion Headquarters just before 6pm, but by this time sections had lost touch and troops were scattered all over the hills. At 6.25pm Lt Col Ross realised that contact had been lost with the enemy, so he ordered the Battalion to concentrate, bringing in their casualties and any enemy dead. Twelve bodies and two prisoners were brought in, but it was thought that up to 30 casualties had been inflicted on the rebels. 2nd Queen’s suffered two killed and three wounded.

This confused engagement can best be summed up by quoting firstly from Lt Col Ross’s report concerning the RAF’s contribution, and then by reproducing the citation which recommended the award of the DCM to CSM W. Webb of ‘C’ Company.

« Previous ![]() Back to List

Back to List ![]() Next »

Next »

Related