Major Patrick Ferguson 1744-80

(The 70th Foot, 1768-80)

|

| Patrick Ferguson as Captain of a Light Infantry Company, 70th Regiment, miniature c1774-77 |

Patrick Ferguson was born on 24th May (OS)/4 June (NS) 1744, most probably in his family's home at 333 High Street, Edinburgh, east of Roxburgh's Close. (Although his father owned the Pitfour estate in Buchan, Patrick does not appear to have visited it until 1762.) His father, James Ferguson of Pitfour, was an advocate, after 1764, a judge, his mother a sister of the prominent literary patron Patrick Murray, Baron Elibank. His family was at the heart of the Scottish Enlightenment - they knew the Ramsays, Hume, Home, Smollett, Adam Ferguson, & c.

In 1756, when Patrick was 12, his father purchased an ensigncy for him in his uncle Colonel James Murray's regiment, the 15th Foot, but it was cancelled since, with war brewing, he was too "young & little" to be of service. In 1759, shortly after his fifteenth birthday, Patrick was bought a Cornetcy in the Royal North British Dragoons (Scots Greys). However, he did not join his regiment until 1761. For nearly two years he studied at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, on the recommendation of his uncle (by then General Murray - Wolfe's successor, and Military Governor of Quebec). There he developed a lifelong interest in the design of fortifications, under the tuition of the noted expert John Muller.

Patrick embarked for Germany with his regiment in spring 1761, to serve in the Seven Years' War. His active service was cut short at the turn of 1761-2 by a leg ailment, probably synovial tuberculosis, which kept him bedridden in Osnabrück for six months. He returned home in summer 1762, and spent a year convalescing in Edinburgh with his parents, and at Pitfour with his father's unmarried older sister, Aunt Betty. With rest, he recovered, but remained prone to arthritis if he overtaxed his leg.

Patrick returned to the Greys in August 1763. He spent the next 5 years travelling around Britain with them from Kelso as far south as Kent and East Sussex on garrison and policing duty. In 1766, Patrick twice visited France. On his first visit, he went to see the Jacobite Lord Ogilvy, widower of his cousin Margaret Johnstone. On the second trip, he intended to study at a French military academy in Angers, but was sidetracked by the social life of Paris.

In 1768, Patrick purchased a company in his cousin Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Johnstone's regiment, 70th Foot. The commission was cheap, since the regiment was sailing for the West Indies, for garrison duty on islands ceded by the French in 1763. Patrick arrived

in spring 1769. He combated scurvy among his troops by making them cultivate their own fruit and vegetables. He also taught himself to play the fiddle. Taking a lead from his cousin Colonel Johnstone, who had purchased a plantation, Patrick bought a sugar estate for the family at Castara on Tobago. But by 1771 his health was suffering.

Circumstantial evidence suggests his arthritic leg was troubling him again. He returned to Britain via either Boston or New York in 1772, before the rest of his regiment took part in quelling the Carib Revolt. His younger brother George sailed out to replace him as "laird" of Castara.

In 1768, Patrick purchased a company in his cousin Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Johnstone's regiment, 70th Foot. The commission was cheap, since the regiment was sailing for the West Indies, for garrison duty on islands ceded by the French in 1763. Patrick arrived

in spring 1769. He combated scurvy among his troops by making them cultivate their own fruit and vegetables. He also taught himself to play the fiddle. Taking a lead from his cousin Colonel Johnstone, who had purchased a plantation, Patrick bought a sugar estate for the family at Castara on Tobago. But by 1771 his health was suffering.

Circumstantial evidence suggests his arthritic leg was troubling him again. He returned to Britain via either Boston or New York in 1772, before the rest of his regiment took part in quelling the Carib Revolt. His younger brother George sailed out to replace him as "laird" of Castara.

Patrick was living in London in 1773. In 1774, when the rest of his regiment, depleted more by tropical disease than by fighting, had returned home, they were re-organised in accordance with General Sir William Howe's 1771 scheme to establish permanent light companies in all infantry regiments. Patrick took part in a training camp for Light Infantry. His interest in and aptitude for light infantry work drew Howe's attention even at this early stage - and the General would remember him 2 years later.

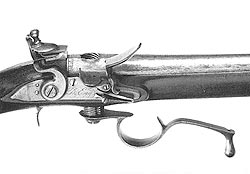

Ferguson rifle diagram, from Jame Ferguson.

In about 1775, Patrick embarked upon designing the Ferguson Rifle, a modification of Chaumette and Bidet's breechloading system for military use. At the turn of 1775-6, he was back in Scotland. In April, he went to London to try to interest General Lord Townshend in his rifle design. He eventually succeeded, and by May was at the Tower of London, supervising the making of trial models and taking part in tests before leading generals and dignitaries. The trial on 1st June received full coverage in the Annual Register. On 4th July, while the Rebel Continental Congress voted for independence and sent its declaration for publication, Patrick was in Birmingham supervising the manufacture of the first 100 Ferguson Rifles for military service. Patrick presented the King with sketches and a description of the rifle. He also demonstrated it before the King and Queen at Windsor. Via Major Cuyler, Howe's ADC, he received the General's backing, and petitioned the King to command an experimental rifle corps in the Colonies. The rifle patent was approved on 2nd December 1776, and he also received private orders from individual officers and the East India Company. These helped his finances: he had got into debt through paying for the early models and trials from his own Captain's pay, and had been obliged to borrow money from relatives to pay for the patent. He was already working on a small field-gun.

In January 1777 he received permission from Townshend and General Harvey to train 200 recruits at Chatham for his experimental corps. However, with news of defeats at Trenton and Princeton, he was ordered to make ready more quickly, with only 100 men. He officially received his command on 6th March. His instructions were that at the end of one campaign, he and his men were to be returned to their original regiments, unless Howe specified otherwise.

In March 1777, Patrick and his corps sailed on the Christopher to New York, where they arrived on 26th May. His experimental field piece blew up in its first test, having been sent out with the wrong size of ammunition. However, the corps - uniformed in the green cloth which had been sent out with them - saw some action in New Jersey. They took part in the expedition to the Chesapeake, where Howe, a light infantry enthusiast, was impressed with them. He assured Patrick that he intended to expand the rifle corps. Unfortunately, events at Brandywine on 11th September 1777 ended these prospects.

Ferguson's Corps performed well in the battle, fighting alongside the Queen's Rangers, under James Wemyss. Unfortunately, Patrick's right elbow joint was shattered by a musket ball. He spent the winter in Philadelphia, under threat of amputation and possible death, enduring numerous un-anaesthetised operations to remove the bone splinters which repeatedly broke open his wounds. In November, he also received word that his father had died in June. Yet in letters home, dictated or scrawled left-handed, he joked courageously about his operations.

Patrick kept his right arm, but it was crippled, permanently bent at the elbow: he later received the King's Bounty for its effective loss. He learned to write, fence and shoot left-handed. It was 13th May 1778 before he was fit to return to duty - still wearing a sling. His rifle corps had been disbanded. This fact has given rise to a variety of dubious conspiracy theories, especially in American secondary works: claims that the corps was suspended because of Howe's 'jealousy', but this is untrue. The rifle company had been set up as an experiment, a field trial for one campaign only. As already noted, Patrick's orders were that he was to return to his own regiment at the end of that campaign, unless Howe "should have a further occasion for his services". What further services could be expected from a rifleman with a smashed arm, threatened with amputation? Under 18 century medical conditions, it was not unreasonable to assume he would never again be fit for command. Besides, Howe, who had first noticed him in 1774, and been supportive, was on the point of going home to Britain just as Patrick returned to duty.

Patrick accepted that he would have to wait until he too returned to Britain before he could devote more time to perfecting his rifle, and does not seem to have lost much sleep over it. He was less obsessive about that particular project than many later American writers on it have been. He threw his energies into building a working relationship with Howe's successor, Sir Henry Clinton. His first engagement since he was disabled was the battle of Monmouth, NJ, but his rôle in it remains obscure. Back in New York, he impressed Clinton with treatises on strategy and military ethics. He was given command of a new unit of light troops, a mixed command of regulars and Loyal Americans. Barely a year after he was disabled, he led them on daring raids against Rebel salt works and privateer bases at Chestnut Neck and Egg Harbor in New Jersey (15th October 1778). Heavy casualties were inflicted on the enemy, but he tried to avoid harming civilians.

Early in 1779, Patrick led reconnaissance and mapping missions in New York and New Jersey. His warnings to Clinton about the weak fortifications on the Hudson were confirmed when Stony Point fell to the Rebels on 16th July. On its return to British hands 2 days later, he was given the task of refortifying it. Clinton appointed him Governor and Commandant of Stony Point and of Verplanck's Point on the opposite bank. Patrick expended much time and effort on this post, only to be ordered to dismantle the works and withdraw in autumn.

In December he was given command of the American Volunteers, made up of New York and New Jersey Loyalists. They set sail on 26th December 1779, landing at Tybee a month later. On 7th February 1780 at Savannah, Clinton formalised Patrick's provincial brevet as Lieutenant Colonel of the American Volunteers, backdated to the beginning of December. While in Savannah, Patrick drew up designs for refortifying the city.

On 14th March, Patrick was bayoneted through the left arm in a 'friendly fire' incident at MacPherson's Plantation, SC, when Major Charles Cochrane and the British Legion infantry mistook his encampment for that of the enemy. For 3 weeks, he had limited use of his one good arm, but chivalrously forgave Cochrane.

During the siege of Charleston, Patrick worked closely with Banastre Tarleton and the British Legion (a Loyal American unit), under the overall command of Lieutenant Colonel James Webster (1740-81), 33rd Foot, to cut off Rebel supply routes. Patrick and Tarleton worked well together, and, contrary to American myth, respected each other. Patrick regarded Tarleton, a Liverpool shipping magnate's son, as "a very active gallant young man", and the latter wrote well of him in his Campaigns. They defeated Huger at Monck's Corner on 14th April. They also co-operated on disciplinary issues: that night 2 drunken Legion troopers, celebrating the victory, broke into Fair Lawn Plantation. One of them, Henry McDonagh, threatened the lady of the house, Jane Giles - a young Englishwoman whose first husband had been Sir John Colleton, Bt. - and 2 of her companions, and sexually assaulted a fourth woman, Anna Fayssoux, the wife of a Rebel army surgeon. Patrick and Tarleton sent men to arrest McDonagh, who was sent to headquarters for court-martial. The papers concerning the case were signed by both officers.

On 18th April, Clinton confirmed Patrick in a permanent promotion, a Majority in the 71st Foot (Fraser's Highlanders), back-dated to the previous October. Patrick therefore gave up his brevet Lieutenant Colonelcy, although he never served with the 71st Foot as a regimental officer. He and his American Volunteers took part in the capture of Fort Moultrie, of which they took command on 16th May, 4 days after the surrender of Charleston. He began to devise plans for erecting fortifications to defend all the principal roads and communications by land and sea in the province.

On 22 May, Patrick was appointed Inspector of Militia by Clinton, to recruit and train local Loyalists, a post for which he refused to accept any additional pay. He left Charleston on 26th May to march up country. In June, he raised a regiment of 240 men at Orangeburg, but his base for most of that summer was around Fort Ninety-Six. The militia flocked to him, and he began training them to respond to signals from his light infantry silver whistle.

Clinton had by now been succeeded by Charles, Lord Cornwallis, as commander in the South. Cornwallis was less enthusiastic about using militia, and also generally favoured his own appointees. This caused problems for Patrick, since one of them, Lieutenant Colonel Nisbet Balfour, was Commandant at Ninety-Six. Patrick had begun designing fortifications for Ninety-Six, which he had forwarded directly to Cornwallis and Clinton, not via Balfour, who often complained about him in his letters to Cornwallis. But by August, rivalries at Ninety-Six had eased. Balfour was posted to Charleston and replaced by Lieutenant Colonel John Harris Cruger, a New Yorker. Work on Ninety-Six's defences was under way by early September.

Patrick's men had been pursuing Clarke, who defeated Loyal militia at Musgrove's Mill on 18th August. At Winn's Plantation the next day, Patrick learned of the major victory at Camden. He then set out to pursue Sumter, but on 21st August learned that Tarleton had surprised and defeated Sumter at Fishing Creek. On 23rd August, Patrick rode to Camden to get new instructions from Cornwallis. He was to operate on the left flank, detached from the main body of the army: to aid the Loyalists, and forage from and punish the Rebels. Cornwallis had misgivings about his chances, yet nevertheless authorised him to do this - a decision he would regret, and for which Sir Henry Clinton later castigated him.

Patrick marched his men up into North Carolina on 7th September. Leaving most encamped, he took 50 American Volunteers and 300 militia towards Gilbert Town and Cane Creek, to surprise McDowell. But McDowell, like Clarke, Shelby and Williams, had withdrawn into the Back Country. Patrick paroled a prisoner to warn these Rebels "that if they did not desist from opposition... he would march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword". Shelby passed on the message to Sevier, of the Washington County Militia. They mobilised the other militias along the Watauga. At Sycamore Shoals on 25th September, they were joined by forces from Georgia, Virginia and the Carolinas. Incited by the fanatical Rev. Samuel Doak's sermons to wield "the Sword of the Lord and of Gideon" in a holy war, they intended to destroy Patrick Ferguson and his army.

|

| An idealised portrait of Patrick Ferguson 1976, by Robert Windsor Wilson. (King's Mountain National Military Park) |

Meanwhile, Patrick won numerous people over to the Loyal cause. On 24th September, 500 men came in. He and his troops left Gilbert Town on 27th September. He learned of the large Rebel advance from deserters from Sevier. Patrick wrote to Cornwallis, then in Charlotte, and to Cruger at Ninety-Six for support. Cruger could spare none, and advised retreat. On 1st October, at Denard's Ford, Patrick wrote to Cornwallis that more Rebels were mustering. He reported that two old men - survivors of a party of 4 - had just been brought into camp "most barbarously maimd by a Party of Clevelands Men". The incident angered him: he used it in an impassioned proclamation that day to rally the Loyalists:

He began to withdraw towards Charlotte, and wrote to Cornwallis requesting support. The Legion could not be sent out immediately, because Tarleton had been seriously ill with yellow fever or malaria, and was still weak. Instead, Cornwallis ordered Patrick to rendezvous with Major Archibald McArthur and the 71st at Arness Ford.

On 6th October, Patrick and his troops set off towards Charlotte, but encamped at King's Mountain (now a National Park), to wait for McArthur's approach. An anecdote collected by Draper in 1874 suggests Patrick spent his last evening with his 2 doxies, Virginia Sal - a buxom young redhead - and Virginia Poll or Paul(ina). Another of Draper's correspondents, Wallace Moore Reinhardt, suggested one may have been a Miss Featherstone, and their shared epithet suggests they may have been Loyal refugees from Virginia.

The following afternoon, the Rebel forces surrounded King's Mountain and launched a surprise assault. Incited by Doak's sermon and by exaggerated reports that Tarleton had 'massacred' Buford's command at Waxhaws in May, their countersign was "Buford". The implication was "No quarter" for Ferguson and his men - or his women. Sal's bright red hair made her an easy target: among the first casualties, she was shot as she helped one of the wounded to the tents.

The Loyalist militia, running low on ammunition, began to fall back. Some 70 uniformed American Volunteers bore the brunt of the fighting. They raced from one side of the mountain to the other, making bayonet charges that thrice succeeded in driving back the Rebels - but only briefly. Patrick was in the thick of the action, sword in hand, riding to the weakest points of the line to rally his men, signalling with his famous whistle. Two horses were shot from under him. He took a third. It was a grey: his career had come full circle.

Knowing that there was scant hope of quarter, he swore he "never would yield to such a damn'd banditti". With two other mounted militia officers, Colonel Vezey Husbands and Major Daniel Plummer, he led a last, desperate attempt to break the enemy line and, sword drawn, spurred his horse forward - into a blaze of rifle-fire.

|

| Patrick Ferguson's grave at King's Mountain National Military Park, South Carolina. |

Husbands was killed outright, Plummer badly wounded. Patrick himself was a conspicuous target, with his sword in his left hand, his bent-up right arm, and a checked duster-shirt protecting his staff-officer's uniform. A massive volley blasted him from the saddle. About a dozen balls shattered his body. His foot caught in the stirrup of his horse as he fell, and he was dragged along the ground. He died within minutes, in the arms of his friends. Jubilant Rebels stripped and urinated on his corpse, before his orderly Elias Powell and other companions were allowed to bathe and shroud him in a raw beef-hide. He was buried in a shallow grave, beside Sal, from whose corpse a Rebel took a necklace of glass beads. Poll was taken prisoner, but released at Moravian Towns and returned to the army in Charlotte, where she apparently found a new protector.

"Don't kill any more! It's murder!" the Rebels' nominal commander, William Campbell protested as, with cries of "Give them Buford's play!" and "Tarleton's Quarter!", they ignored the Loyalists' white flags. Only with great difficulty did he prevent a wholesale massacre. Rebel casualties were 28 dead and 64 wounded, but 157 Loyalists were killed, and 163 so seriously hurt that they were abandoned on the mountain. Some were rescued by local Loyalists, and nursed back to health. Others were less fortunate: for weeks afterwards, turkey-buzzards, wolves and hogs fattened themselves on human carrion.

The rest - nearly 700 men, including walking wounded - were marched off as prisoners. Along the way, they were ill-used, even hacked with swords. Campbell had to order his officers to "restrain the disorderly manner of slaughtering and disturbing the prisoners". At Red Chimneys - plantation of Aaron Bickerstaff, a Loyalist Captain mortally wounded in the battle - nine militia officers were hanged from a tree after 'trial'. Another man was hanged for trying to escape. Cleveland beat up Uzal Johnson, the young New Jersey doctor, "for attempting to dress a man whom they had cut on the march", his friend Lieutenant Anthony Allaire (American Volunteers), wrote.

Tarleton and the Legion arrived 3 days too late, and learned the worst. Tarleton later wrote in his Campaigns: "the death of the gallant Ferguson threw his whole corps into total confusion... The mountaineers, it is reported, used every insult and indignity, after the action, towards the dead body of Major Ferguson, and exercised horrid cruelties on the prisoners that fell into their possession."

|

| Mausoleum of the Fergusons of Pitfour, erected 1775, Greyfriars Kirkyard, Ediburgh . |

News of Patrick's death reached his family in Edinburgh about 10 days before Christmas.

While his family lies in a mausoleum in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh, the "King of the Mountain" is still on King's Mountain. He was the only British serviceman in the battle: all the others were Loyal Americans. But not all was lost, nor was the sacrifice in vain. Some of them - including de Peyster and Allaire - later settled in Canada - a country which still honours the contribution to its development made by thousands of Loyal American refugees.

The cairn on Patrick's grave post-dates the 1880 centenary, and is accompanied by a headstone erected in 1930. The inscription is generous, although it contains several mistakes: his rank, his regiment (the modern HLI is not the same 71st as Fraser's Highlanders), and his birthplace. Sadly, 'Virginia Sal', who lies beside him, is not mentioned, nor is there any monument to his men.

| TO THE MEMORY OF COL. PATRICK FERGUSON SEVENTY-FIRST REGIMENT, HIGHLAND LIGHT INFANTRY. --- BORN IN ABERDEENSHIRE, SCOTLAND IN 1744, KILLED OCTOBER 7, 1780 IN ACTION AT KING'S MOUNTAIN WHILE IN COMMAND OF THE BRITISH TROOPS. --- A SOLDIER OF MILITARY DISTINCTION AND OF HONOR. --- THIS MEMORIAL IS FROM THE CITIZENS OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN TOKEN OF THEIR APPRECIATION OF THE BONDS OF FRIENDSHIP AND PEACE BETWEEN THEM AND THE CITIZENS OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE. --- ERECTED OCTOBER 7, 1930. |

|

| The Ferguson rifle. © The Board of Trustees of the Armouries |

Patrick Ferguson And The Royal Armouries

In the history of British military firearms very few are of such rarity or have stimulated such interest in students of the period or of the development of weapons as the breech-loading flintlock rifle developed by Captain Patrick Ferguson.

His rifle had a screw-plug breech mechanism which was an improved version of an earlier design, but these improvements, patented by Ferguson in 1776, a year of exceptional importance in Britain’s confrontation with its American colonies, made the rifle a practical and serviceable military weapon. A demonstration of the rifle by Ferguson himself before a group of senior British officers convinced them of its military value, and a company armed with the new weapon was ordered to be raised.

The Royal Armouries is the British national museum of arms and armour and contains collections which include weapons tested and used by British forces from the sixteenth century to the present day. Despite the strength of its collections it until recently held no example of the Ferguson rifle, so in November 2000, when an exceptionally fine example, whish had been part of the remarkable collection of the late William Keith Neal, was to be auctioned in London, the Royal Armouries made a particular effort to acquire it. That rifle was made for Patrick Ferguson by the Famous London gunmaker, Durs Egg. Built in the plain but elegant military style of the period it almost certainly represents the pattern for the rifles made by the Board of Ordnance for issue to Ferguson’s special rifle company.

The provenance of this rifle is fascinating and unimpeachable, since until it was acquired by Mr Neal in the 1960s it had remained in the Ferguson family home at Pitfour, Scotland. In its bid to acquire the rifle the Royal Armouries received invaluable support from the Heritage Lottery Fund. This exceptionally rare rifle now forms an important part of the display relating to the American War of Independence within the War Gallery in the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds.

Students of British military firearms and of military history have keenly awaited a full and detailed biography of Patrick Ferguson, so Dr Gilchrist’s work will receive an enthusiastic reception. It is good for them to know too that one of the best surviving examples of his rifle is now preserved, for study and for posterity, in the nation’s premier arms and armour collection.

Graeme Rimer

Head of Collections, Royal Armouries

Acknowledgements

The Association is most

grateful for the assistance of Doctor MM Gilchrist for supplying the text for

the article published on this web-site. Dr Gilchrist is the author of "Patrick Ferguson" "A Man of Some Genius".

Related