Captain (later Baron Freyberg of Wellington and Munstead)

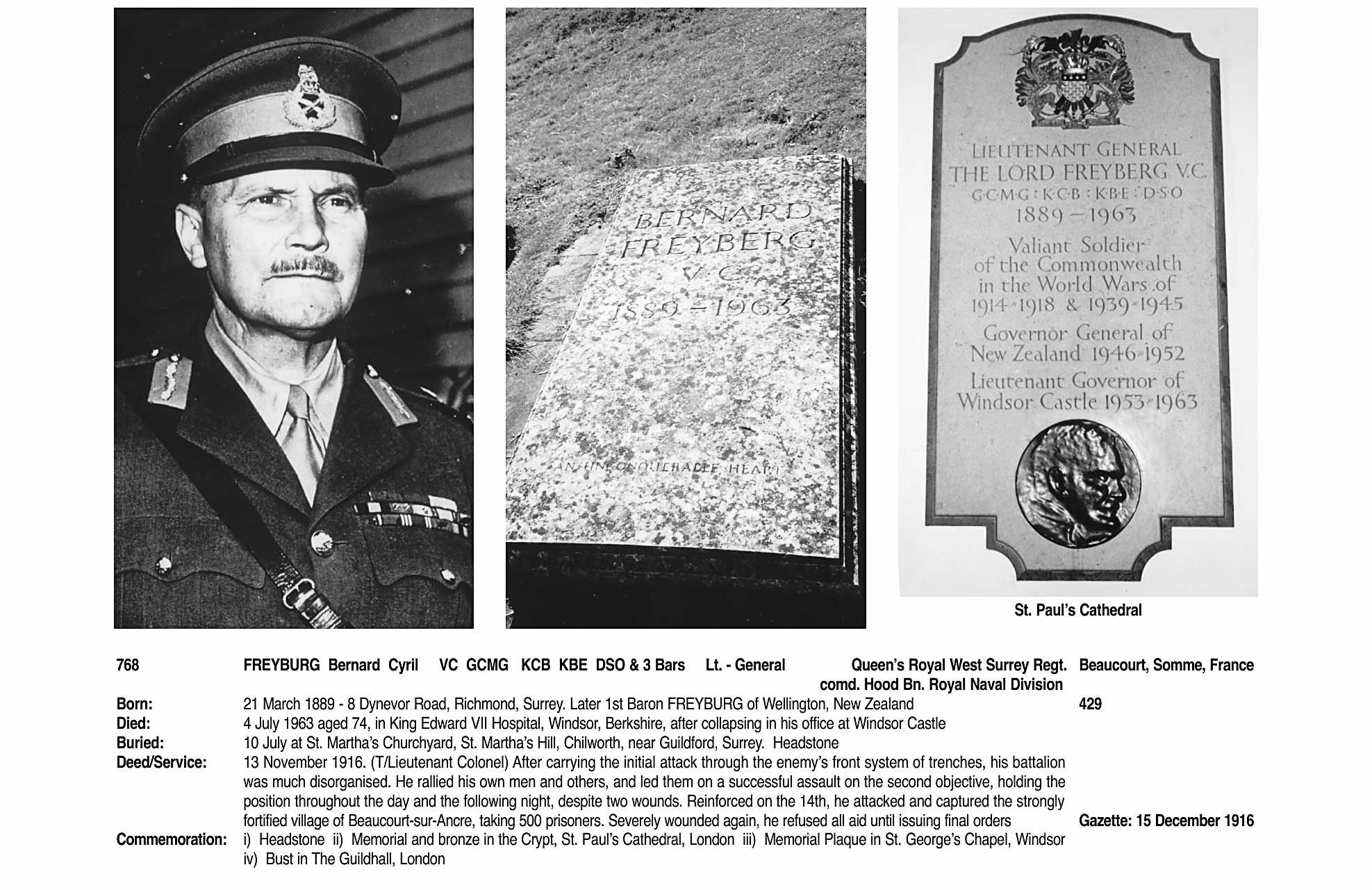

Bernard Cyril Freyberg VC GCMG DSO KCB KBE DSO (three bars)

The Queen's (Royal West Surrey) Regiment

|

| Captain Bernard Cyril Freyberg VC |

Born at Richmond Hill, London, in 1889 and educated in New Zealand at Wellington College, Freyberg served in the New Zealand Forces from 1911-13 and then returned to England to study dentistry. On 13th November 1916, while serving in The Queen’s, and commanding The Hood Battalion, Royal Naval Division at Beaucourt-Sur-Ancre, France, he led an initial attack straight through the enemy’s front system of trenches.

After capturing the first objective Freyberg’s command became disorganised due to mist and heavy fire. Although four times wounded he continually rallied and re-formed his men, personally leading an assault which resulted in the capture of a village and five hundred prisoners. Although suffering from his wounds, which were of a severe nature, he refused to leave the line until he had issued his final instructions. Through his valour the most advanced object of his Corps were permanently held.

He was decorated with his Victoria Cross by HM King George V at Buckingham Palace on 2nd January 1918 and was awarded another Bar to his DSO on 11th November 1918.

After the war he gained several promotions and appointments retiring as Major-General in 1937. Returning to active service in November 1939, he was chosen to command the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and saw service in Crete, North Africa and Italy, gaining a third Bar to his DSO in the process. Later becoming Governor-General of New Zealand and Deputy Constable and Lieutenant-Governor of Windsor Castle, he died as Baron Freyberg of Wellington (NZ) and Munstead VC, GCMG, DSO two bars, LLD, DLL in 1963, and is buried at St Martha-on-the-Hill Church, Surrey.

In the May 2009 edition of Medal News there is an excellent article on General Freyberg under the heading 'Naval VC on the Somme'. The auther, Mr Ron Gittings and the Editor of Medal News, Mr John Mussell FRGS have very kindly agreed for the article to be reproduced on our web-site. Our very grateful thanks to these gentlemen for their assistance. |

Naval VC on the Somme

Ron Gittings

The Battle of the Somme, as far as the infantry were concerned at least, started with Zero Hour at 0730hrs on July 1, 1916. The thousands, both British and French, that waited in the trenches to “go over the top” had been told that it would be a “walk over”. Most of them had made a long approach marches throughout the night to get in position and were tired even before they started the attack. Certainly, the week long artillery barrage on the German trenches and barbed wire gave the impression that no-one could be left alive after such a pounding. However, the Germans were well dug in, often with bunkers as deep as 40 feet, and the wire wasn’t cut as well as it should have been in some places. The French, attacking at the southern end of the front, had more success than the British. Their objective were more limited and their artillery more flexible. Their Forward Observation Officers were able to call down fire as it was required. The British artillery, on the other hand, worked to a strict timetable. This often meant that the barrage had moved on before the infantry had been able to regroup and able to advance, leaving them fatally exposed to murderous German machine-gun fire.

The day was to become known as the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army. British Expeditionary Force (BEF) losses on that day were staggering-57,460 casualties. 19,240 were killed or would die of wounds, 35,493 were wounded, 2,152 were missing and 585 were taken prisoner. German records of their losses are more vague, but it's estimated that they lost between 10,000 and 12,000. Total Allied casualties for the offensive were 623,907. Until recently it has been considered to be a great British defeat.

Some modern historians, Gary Sheffield for example, don't view it that way. In his opinion it was a battle that the British Army had to fight in order to win the war! The British Regular Army had all but disappeared during the first battles of the war and Kitchener's New Army, nearly all volunteers, had very little experience. The Somme was most certainly a steep learning curve, in modern parlance, and many lessons were learned. Infantry and artillery tactics were revised to such a degree that the army became a much more formidable fighting force that went on to win. During the 100 day campaign leading to the Armistice they swept all before them, this probably could not have happened had it not been for the Somme. The Germans themselves considered the Somme to be a defeat, one German officer stated that "the Somme was the muddy grave of the German field army".

The war itself saw the formation of new organisations, the Machine Gun Corps and the Royal Flying Corps, for example. Another was the Royal Naval Division.

At the outbreak of the war the Royal Naval Reserves had a surplus of some 30,000 men that could not be found jobs on warships. Largely at the insistence of Winston Churchill, who at the time was the First Lord of the Admiralty, these surplus mariners were formed into what would come to be known as the Royal Naval Division (RND). A Brigade of Marines was formed immediately, two Naval Brigades would follow. Badly equipped and without many of the supporting units that normally go to make up the establishment of a division, the RND went to war.

They took part in the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign, by the end of which there were very few men left who had actually seen service at sea. On April 29, 1916 the division transferred from Admiralty authority to the War Office and was redesignated the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division on July 19 that year.

During the Battle of the Somme the division consisted of 188th Brigade (Anson and Howe Battalions and two battalions of Royal Marines), 189th Brigade (Hood, Nelson, Hawke and Drake Battalions), 190th Brigade (1/Honourable Artillery Company and three battalions of infantry) with 14 (Severn Valley Pioneers) Worcestershire's as their pioneers.

On November 13, five days before the offensive ended, the Commanding Officer of Hood Battalion (he had already won a DSO) won a VC in circumstances, which according to another VC winner, Major William Philip Sidney of the 5th Bn Grenadier Guards, was "probably the most distinguished personal act of the war". (Major Sidney won his VC at Anzio and went on to become Viscount De L'Isle, VC, KG, GCMG, and GCVO).

Bernard Cyril Freyberg, born in Richmond, Surrey, on March 21, 1889, was the seventh son of James Freyberg. His mother, Julia Hamilton, was his father's second wife and Bernard was her fifth son. In 1891 the family moved to Wellington, New Zealand, where James took up an appointment in the forestry department.

Bernard went to Wellington College, leaving at the age of 14 to become apprenticed to a dentist. It was while still at school that the foundations were laid for his future in the military, he became a sergeant in the cadets. He also played rugby, boxed, sailed and rowed. But it was at swimming that he excelled. He competed in the 1905 Australian championships, going on to be the New Zealand junior champion in 1906 and senior champion in 1910. He was finally registered as a professional dentist in 1911, it was a career that he never liked and rarely spoke of it afterwards.

|

| A close up of the plaque on the monument to the men of the Royal Naval Division who fell at the Battle of the Ancre. |

During the years 1905 to 1907 Bernard was a member of D Battery of the New Zealand Field Artillery Volunteers, based in Wellington. But a much more positive start to his military career was to come about when, in late 1911, he was commissioned in the territorial Hauraki Regiment. Following some small adventures he decided that dentistry was, after all, not for him and set sail for San Francisco in March 1914 to seek a better life. Of his life there not much is known, but it's quite probable that he saw action in Mexico, serving with General Francisco "Pancho" Villa. In any event he returned to England at the outbreak of World War 1.

Here he set about seeking a commission, with the help of Major G. S. Richardson (who had, coincidentally, been in the same artillery battery in Wellington!), he was granted a temporary commission as a Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. He was posted to Hood Battalion, before long gaining promotion to Lieutenant-Commander and commanding A Company.

During October Bernard saw action in Belgium, but it was short lived and he was back in England by the end of the month. The RND was sent to Gallipoli at the end of February 1915, but the period between Belgium and then became a very important period in his life and was to set the seal on his future career, militarily and politically. There were brother officers in A Company that were then considered to be the elite of young British manhood, men such as Arthur Asquith and Rupert Brooke would help the inexperienced Bernard to become accustomed to the social and intellectual world to be found at such a level. Thanks to his fellow officers he was to become well known to the Prime Minister (Asquith) and the First Lord of the Admiralty (Churchill), which would stand him in good stead in later years.

At Gallipoli he won great acclaim for a long swim that was to win him the first of four DSOs. During the night of April 25/26, he made a long swim towing behind him a bag of flares. The intention was to fool the Turks into believing that a major landing was about to take place there. He received his first real wound in July when he was shot in the stomach when he was temporarily in command of the battalion, an appointment he now had to relinquish.

He recovered quickly and returned to Gallipoli in August, when he was promoted and given command of Hood. The battalion left the ill-conceived battle with the general evacuation on January 9,1916; only 15 men of the original complement answered the roll call.

Back again in England Bernard decided that a permanent career in the army would be a good move and so applied for a transfer to the British Army. His new contacts doubtless helped, and in May he was gazetted as a Captain in the Royal West Surrey Regiment and as a temporary Lieutenant-Colonel to command Hood Battalion. Towards the end of May the battalion was concentrated on the Western Front in readiness for the new offensive on the Somme. He won his VC during the fighting leading to the capture of the village of Beaucourt (Battle of the Ancre). His citation, gazetted on December 15, explains it all:

"For most conspicuous bravery and brilliant leading as a Battalion Commander. By his splendid personal gallantry he carried the initial attack straight through the enemy'sfront system of trenches. Owing to mist and heavy fire of all descriptions, Lieutenant-Colonel Freyberg's command was much discouraged after the capture of the first objective. He personally rallied and re-formed his men, including men from other units who had become intermixed. During this advance he was twice wounded. He again rallied and re-formed all who were with him, and although unsupported in a very advanced position, he held his ground for the remainder of the day, and throughout the night, under heavy artillery and machine gun fire. When reinforced on the following morning, he organised the attack on a strongly fortified village and showed a fine example of dash in personally leading the assault, capturing the village and five hundred prisoners. In this operation he was again wounded. Later in the afternoon, he was again wounded severely, but refused to leave the line till he had issued final instructions. The personality, valour and utter contempt of danger on the part of this single Officer enabled the lodgement in the most advanced objective of the Corps to be permanently held, and on this point d'appui the line was eventually formed." |

His amazing will to live is shown as a post-script to the action. He was put into a tent with others who were expected to die. As a result he received no treatment other than pain killing drugs! He was later moved, fortunately.

During his recuperation in London he was to be re-acquainted with his future wife, Barbara Mclaren who had lost her husband in August 1917. They married in June 1922. Barbara was the daughter of Sir Herbert and Lady Jekyll, herself the widow of the son of the first Baron Aberconway, she provided a perfect family background.

But by the end of April, Bernard was back on the Western Front and commanding 173rd Brigade (58th Division), the youngest Brigadier-General in the army. In August his division was transferred to Fifth Army in readiness for the Battle of Passchendale. During the Battle of Menin Road Bernard was severely wounded again, receiving five penetrating shrapnel wounds from an artillery shell. Further recuperation followed and in January 1918 Bernard was commanding 88th Infantry Brigade (29th Division) and was involved in the Battle of Ypres (Wipers as it was called by the British Tommy). He received his ninth wound of the war on June 3!

He was awarded a bar to his DSO for his involvement in the battle. On November 11 he received a second bar to his DSO, just minutes before the Armistice. He had been ordered to seize the bridge at Lessines (Belgium); this was achieved on horseback leading a squadron from the 7th Dragoon Guards. But the war was over and he had his future to think about.

Forced now to revert to his substantive rank of Captain he applied for a commission in the Grenadier Guards. He was still suffering from his wounds and so decided to undertake a long sea voyage to New Zealand, partly to aid his recovery and also to see his mother. Once completed and back in England he was appointed to the staff of 44th (Home Counties) Division in Woolwich.

His military career continued. In January 1935 he was appointed General Officer Commanding (GOC) in the Assam district of the eastern command in India.

The site of the action of the Royal Naval Division and where Freyberg won his VC, the photo was taken from the church yard

looking down into the valley. Thiepval Wood can be seen on the skyline at the top left of the picture.

In February 1936 he was created Knights Commander, The Most Honourable Order of the Bath (KCB). But fate was about to deal him a nasty blow. A routine medical board detected an irregular heart beat and his appointment to India was cancelled. He retired on half pay in September 1937.

Never one to take setbacks lightly, he eventually managed to get his medical grading re-appraised. Now with a medical grading that meant he was fit only for home service he took up the appointment of GOC Salisbury Plain on September 3, 1939.

New Zealand declared war on Nazi Germany on September 3 and a few weeks later Bernard offered his services to the government of New Zealand. To that end he met with Peter Frazer, New Zealand's Deputy Prime Minister. Following discussions with the Government of New Zealand, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff and Winston Churchill, Bernard was told on November 16 that he would assume command of New Zealand's Expeditionary Force (2NZEF). He would remain a British officer on loan to New Zealand.

Bernard was to remain in command of the NZEF throughout their operations in Crete, North Africa and Italy. The German invasion of Crete was the only occasion on which Bernard's command of the force came into contention. He failed to notify the New Zealand Government of his belief that there was insufficient air cover and equipment to repel any attack. This was a genuine mistake on his part as he firmly believed that the government had been made aware of the situation by either Wavell or Eden. The Allies were aware of the impending invasion of Crete thanks to decoded information from the German Enigma machine, Bernard's failure to deny the main landing area to the Germans proved to be decisive. New Zealand's Prime Minister, Peter Frazer, was of the opinion that he had committed their forces without sufficient consultation. Bernard was able to convince him that this had not been the case, and with glowing commendations from the Chief of the Imperial General Staff and Wavell, Frazer's confidence in him returned. For the remainder of the war this confidence remained unwavering and was fully justified. He was made a Knights Commander of The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (KBE) in the 1942 New Zealand honours list for his skilful command in Greece and Crete, finally settling the issue of that government's faith in him.

In Africa the New Zealanders became Rommel's most feared antagonists. But, leading from the front, as was his style, caused Bernard to receive another severe wound, this time to the neck. Before this, however, he had accepted the surrender of the Italian Field Marshal Messe, who was the supreme Axis commander in North Africa.

On to Italy, where the New Zealanders were involved in the Battle of Monte Cassino. Bernard was of the opinion that the hill could not be taken by a frontal assault and informed his superior, General Alexander, that he would withdraw his force if their casualties reached 1,000. Plans were changed when New Zealand casualties reached 998; the division began an outflanking manoeuvre instead. Monte Cassino fell finally on May 18,1944.

Towards the end of the war Bernard was awarded a third bar to his DSO and created Commander of the United States Legion of Merit.

With the cessation of hostilities Bernard gave up the command of 2NZEF on November 22, 1945. He would remain on the British Army list until he retired, with the rank of Lieutenant-General, on September 10, 1946. Earlier that year he became GCMG (Knights Grand Cross).

He was offered the position of Governor-General of New Zealand and was sworn in on June 17, 1946. His time there was busy with many official duties to be carried out; he said later that his six years as Governor-General were the happiest of his life.

He was created a baron in 1951 and took the title Baron Freyberg of Wellington, New Zealand and of Munstead (in Surrey). He left Wellington for the last time on August 15,1952. He was given a tumultuous send off, the like of which had never been seen there before.

In England he took up his final position, that of Lieutenant-Governor and Constable of Windsor Castle, his official residence would be the Norman Tower. During his time in this post, amongst many official duties, he played a leading role in the conferring of the Order of the Garter on Winston Churchill. He also had a role to play in the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. He represented New Zealand at the Alamein Reunion in 1952, where he sat with Winston Churchill and Field Marshals Montgomery and Alexander. An event which he said afterwards gave him great personal satisfaction was to command the parade at the celebration of the founding of the Victoria Cross, held in Hyde Park on June 26, 1956.

Towards the end of his life his health deteriorated and he suffered with Parkinson's disease and hardening of the arteries to the brain. On July 4, 1963 he suffered a rupture of the stomach, directly attributable to the stomach wound received at Gallipoli. He died later that night, he was 74. Lieutenant-General Lord Freyberg, VC, GCMG, KCB, KBE, DSO and three bars is buried at St Martha-on-the-Hill Church, Surrey.

(Click image to view enlarged)

Related Links

External websites: