Queen's in the Middle East

The Turning Tide

Enter Rommel And Crete

2nd Queen’s disembarked at Alexandria and entrained for El Tahag camp, about 5 miles east of Tel-el-Kebir. After five weeks of hard training in that area, 16 Brigade moved to Kabrit on the Bitter Lakes, halfway between Suez and Ismailia, where they started practising with landing-craft and were issued with maps of a mountainous island, later identified as Rhodes. For this operation it was intended to form the 6th Division consisting of 16 Brigade, a Guards Brigade and a Polish Brigade. It promised to be a fine division, but it never functioned as one.

During this period the best units of XIII Corps had been detached and sent to Greece in response to the Greek government’s appeal for help because of the probable intervention of German forces in their war against the Italians. These included the 6th Australian Division and an armoured brigade from the 2nd Armoured Division, which left the poorly equipped 3rd Armoured Brigade and the newly arrived 9th Australian Division to hold the western part of Cyenaica. Upon this scene appeared Generalleutnant Erwin Johannes Eugen Rommel.

Rommel soon discovered the British weakness around El Agheila. He had received his appointment from Hitler, so he was to a large extent immune from censure when exceeding his authority. He decided “ .... to depart from my instructions to confine myself to a reconnaissance and to take command at the front into my own hands as soon as possible.” Having bullied the Italians into making some show of holding a position at Sirte, he then sent a mixed German-Italian force forward to beyond Nofilia as soon as the first elements of the Deutsche Afrika Korps arrived on the 17th February. On the 31st March, having received the bulk of his leading division (the 5th Light Division) but not waiting for the arrival of 15th Panzer Division, he launched an offensive despite orders to delay this until the end of May. This stroke was so successful that XIII Corps evacuated Benghazi on the 3rd April. Indeed by then Corps Headquarters had lost control of the situation, and 2nd Armoured Division units, together with the corps troops and services, began to move in an uncoordinated manner to the rear. This episode became known as ‘The Benghazi Handicap’. Only the 9th Australian Division maintained some form of cohesion and twice flung back heavy German attacks. Mechili fell to the Afrika Korps on the morning of the 8th April, followed by Derna and Gazala, where Major-General L.J. Morshead, GOC of the 9th Australian Division, formed a line through which came random groups of British and Indian units, whilst the Australian 18th and 24th Brigades were hard at work on the Tobruk defences. On the 11th April Tobruk was surrounded, but all attacks on the fortress over the next six days were repulsed by highly accurate British artillery fire and murderous Australian rifle fire. Rommel decided to by-pass Tobruk, but his advance had by now lost its momentum and could only push the British back to the Buq Buq-Sofafi line.

As a result of this enemy offensive the formation of the 6th Division was abandoned, and the brigades were rushed separately to the desert. 2nd Queen’s left Kabrit hurriedly on the 9th April to occupy forward positions round Mersa Matruh. On the 23rd April the Battalion was relieved by the 31st Australian Infantry and moved back to the same positions that they had occupied in the Baqqush Box the previous autumn. By early May it had become clear that until the enemy had reduced Tobruk he could advance no further, so 2nd Queen’s were ordered to a concentration area some 50 miles east at El Daba.

The move to El Daba was a nightmare since a khamseen blew up and there developed an impenetrable sandstorm. The vehicles in which the companies travelled, whether by road or rail, became so hot that there were several cases of heatstroke. However the El Daba camp was pleasant, the moisture of the flats preventing any dust storms, and there was superb bathing. Unfortunately for ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies some airfields near Sidi Barrani required guarding and they were detached for these duties. On the 18th May the Battalion concentrated again and moved to the great staging camp at Amariya, a few miles from Alexandria. From there they witnessed the almost nightly air-raids that were being made on that city.

Things had not gone well with our forces in Greece either. When the Germans invaded with powerful armoured formations the gallant Greek defence collapsed. The British force, less most of its equipment, was evacuated with great difficulty from the small harbours of the Peloponnese. Many of these troops were then landed in Crete, and King George of Greece made Crete his last stronghold.

On the 20th May the Germans launched an airborne invasion of the island. The main attack was undertaken with parachute formations, followed by gliders and troop carriers. It was the first airborne operation on such a scale ever attempted. A seaborne expedition, a Mountain Division, had also attempted to cross to Crete using caiques escorted by torpedo-boats, but was overwhelmed and almost completely destroyed by Royal Navy cruisers and destroyers. Only a few E-boats escaped, and it was estimated that 4,000 troops perished in these short, sharp actions. The airborne invasion had greater success, since Crete was within fighter range of Greece but beyond fighter range from Egypt. By using concentrated and fierce air attacks on the island’s three airfields, eventually a landing ground was captured and the big German troop carriers were able to land.

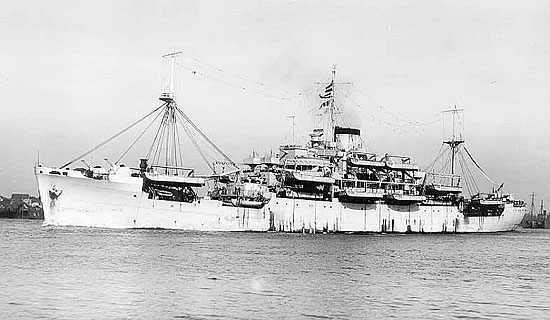

It was at this crisis that 2nd Queen’s was embarked for the island on the 22nd May. The other two battalions of 16 Brigade, 1st Argylls and 2nd Leicesters, had already gone some days previously. They succeeded in landing but had an extremely hard time and many casualties. 2nd Queen’s and Brigade Headquarters embarked in HMS Glenroy, an early form of landing-ship equipped with special craft for getting troops ashore. They were escorted by HMS Coventry, an anti-aircraft cruiser, and one other escort vessel. As soon as they were at sea it was revealed that their destination was to be Tymbaki Bay on the south coast of Crete, and their task was to open up the road from there to Heraklion.

HMS Glenroy.

At 11am on the 23rd May a stick of bombs was dropped by a highflying aircraft about 500 yards astern of the Glenroy. Frequent air alerts followed until 3pm, when an order was received to return to Alexandria. This order was rescinded by special instructions from the Admiralty and the three ships turned north again at about 6pm. However, it soon became clear that the Glenroy could not reach Tymbaki Bay before it was light, and that if she continued northwards daylight would expose her to the worst possible danger from enemy air attacks. Finally she was ordered again to return to Alexandria. 2nd Queen’s disembarked in the early morning of the 25th.

But the situation in Crete was still intensely critical. The seaborne invasion had been smashed; our troops were holding out stubbornly, and there was still a chance of repelling the airborne invasion; but it was desperately important to reinforce them. Another attempt to reach the island was ordered. 2nd Queen’s and Brigade Headquarters therefore re-embarked in the Glenroy at 11am and sailed again for Crete that evening. They were again escorted by the Coventry and also by two destroyers, HMAS Stuart and HMS Jaguar.

At 5pm next day an enemy reconnaissance plane dropped two sticks of bombs without causing damage, but an hour later the convoy, and especially the Glenroy, was heavily attacked by about twelve bombers. There was tremendous anti-aircraft fire from the escort, and although the Glenroy was armed with four 4in guns and four 2pdr pom-poms, 36 LMGs were additionally manned by the Battalion. In spite of this the attacks were determined, carried out by shallow dive-bombing mainly directed at the Glenroy. It was the troops’ first experience of bombing in a ship at sea, and to them it seemed impossible that the ship could survive. Early in the action a splinter from a near miss set fire to the large dump of cased petrol stored on deck. A fire-fighting party, including officers and men of the Queen’s, worked with the greatest courage and devotion, forming a chain from the blazing dump and hurling the four gallon containers into the sea. Meanwhile the LMG gunners and their No. 2s, equally gallant, maintained their fire even when the fires from the blazing fuel almost reached them. The conditions for the rest of the Battalion below decks were almost more trying since they had no activity to distract them and could only sit and listen to the appalling noise. However, the men’s conduct was magnificent, and the officers and NCOs had no difficulty at all in keeping them calm. The attack lasted a little over an hour and was followed by a low-level torpedo attack. Eventually the enemy aircraft withdrew, the fire was extinguished, and it was possible to assess the damage. One landing-craft had been destroyed and three others damaged. One man of the Queen’s had been killed

and nine wounded.

During the action the Glenroy had been forced to turn south for more than an hour to bring the wind aft because of the fire. This delay, the loss of the landing craft and rough weather made the chances of landing that night almost negligible. Again the order was received for the Glenroy and its escort to return to Alexandria. The convoy was shadowed on its return journey and two more sticks of bombs were dropped, but there was no more damage. On the way back a Wellington bomber approached the ship, very low over the water. It was presumed that it had come to find the Glenroy, but it was damaged and ditched alongside. The crew scrambled out and were taken aboard.

The ship anchored in Alexandria harbour on the evening of the 27th May. 2nd Queen’s disembarked next morning and returned to Amariya, The day before it had been decided to evacuate Crete forthwith, and eventually about 15,000 out of the 27,000 defenders were rescued under conditions of great difficulty with grievous losses to the Royal Navy. Three cruisers, six destroyers and 29 other vessels were sunk; whilst a battleship, one aircraft-carrier, three cruisers and another destroyer had been seriously damaged. The defence of Crete had been a most costly operation to the allies, but the German airborne forces had been crippled also. The enemy was never able again to mount such an airborne operation in any theatre during the rest of the war.

« Previous ![]() Back to List

Back to List ![]() Next »

Next »

Related