Queen's in the Middle East

Syria

Amongst those units rescued from Crete were the remnants of the other two battalions of the 16th British Infantry Brigade, both having suffered heavily. The 1st Argylls especially were so low in numbers that they were removed from the Brigade and their place was taken by the 2nd King’s Own from the Cairo Garrison. The Brigade remained in Amariya until the 8th June, and The Glorious First of June was celebrated in the traditional manner with a party in HMS Coventry. 16 Brigade then moved to Qassassin, the great training camp in the Canal Zone. They expected to remain there for some time.

(Author’s note - HMS Coventry was unfortunately sunk by air attack off Tobruk on the 14th September 1942. HMS Glenroy survived the war, and was eventually returned to her owners.)

However, concurrently with the reverses in Cyrenaica and Greece, other enemy strategies were threatening allied security in the Middle East. The first of these to manifest itself was in Iraq, a country which had been artificially created after the First World War from several provinces taken from the Turkish Empire. Iraq had always been a British sphere of influence, and was governed by a pro-British regent, Amir Abdul Illah, since the king was an infant. On the day that Rommel’s forces entered Benghazi a coup d’état took place in Baghdad and Abdul Illah was forced to flee, leaving power in the hands of Raschid Ali el Gailani, a violently pro-Axis politician. Within a month Iraqi forces attacked the RAF flying school at Habbaniya. The flying school had on strength 74 assorted training aircraft, three Gladiators and a Blenheim. At first there was some scattered rifle and machine-gun fire and sporadic shelling, but by the 2nd May five of the assorted training aircraft had been destroyed and their pilots killed, seventeen other people had been killed by shell-fire, and the Iraqi investment force had increased to brigade strength and was supported by the Iraqi Air Force.

Reinforced by eight Wellingtons flown up from Shaiba and by 1st King’s Own from Karachi, the garrison retaliated by bombing and strafing the Iraqi positions and with some aggressive patrolling. At dawn on the 6th May a large portion of the investing army had disappeared. That afternoon two brisk actions were fought with retreating Iraqi columns, in both actions the enemy being thoroughly routed, and the siege was over.

A flying column was hastily cobbled together from the 1st Cavalry Division in Palestine and sent into Iraq for a 500 mile dash to Habbaniya, whilst 10th Indian Division was sent to Basra for an advance on Baghdad. By the end of the month Raschid Ali had fled to Iran, and Abdul Illah was reinstated as regent. Geography had effectively frustrated German designs in Iraq since the distances involved denied them the opportunity to give any material help to Raschid Ali.

The revolt in Iraq had exacerbated the dangerous political situation in Syria, but Syria was by no means shielded from direct Axis intervention by geography. The two provinces of Syria and the Lebanon were ruled by the French under a mandate granted by the League of Nations, similar to that which existed in Palestine. Under the terms of the armistice with France in 1940, an Italo-German commission arrived in Syria in August 1940 and progressively disarmed, demobilised and repatriated the 120,000 strong Army of the Levant, which in the early days of the war had been regarded by Britain as the strongest defence against German aggression in the Middle East. By early 1941 it had been reduced to 35,000 officers and men retained for internal security. These men were all hard-core professional soldiers equipped lavishly with supplies originally intended for the whole of the Army of the Levant. They were commanded by General Henri Dentz, who was strongly pro-Vichy and anti-British.

The official British position regarding Syria was quite clear at this stage. Britain was not at war with Vichy France, but neither the Lebanon nor Syria should be occupied by any hostile power, nor be used as a base for attacks on neighbouring countries in which Britain had an interest. General Wavell was anxious not to provoke the Vichy authorities in view of his numerous other commitments, but the Free French, with General Catroux acting as General de Gaulle’s deputy in the Middle East, believed that the Germans were on the point of invading Syria and that General Dentz would welcome assistance against them from any source, especially the Free French. This Free French intelligence was soon proved to be erroneous, but the German fighters which had attacked Habforce (the flying column to Habbaniya) on its way into Iraq, had undoubtedly been operating from Syrian airfields. This posed the threat that in future the Luftwaffe might launch operations against Egypt and especially the Suez Canal. Wavell reluctantly authorised the planning for Operation Exporter (the invasion of Syria and the Lebanon) and on the 8th June two brigades of the 7th Australian Division, (the third brigade was in Tobruk), the 5th Indian Infantry Brigade from the 4th Indian Division (hastily rushed back from Eritrea), one armoured regiment and one horsed cavalry regiment from the 1st Cavalry Division, a battalion from the Special Service Brigade from Cyprus, and six battalions of Free French under General Legentilhomme, crossed the frontier on three routes.

Southern Syria, 1941.

The objectives were to capture Damascus, Rayak and Beirut as a preliminary to the occupation of the whole country. At first it was thought that the Vichy French would only offer a token resistance, and indeed at the start the advance met little opposition. But by the 13th June all the columns were held up; the Australians on the coastal route at Sidon; the Free French about ten miles short of Damascus around Kiswe; and in the central sector a British battalion was overwhelmed at Kuneitra by a counter-attack of two battalions with tank support. It became very evident that the Vichy French forces showed not the slightest sympathy towards the allies, there were a number of violations of both the white flag and the Red Cross, and the Vichy French treatment of any prisoners they took, especially British or Indian, was abominable.

As a result of the first week’s fighting it was clear to Wavell that reinforcements were necessary. The 6th Division was resuscitated under the command of Major General J.F. Evetts to consist of the 5th Indian Infantry Brigade (already in Syria) and the 16th and 23rd British Infantry Brigades, whilst Habforce was ordered to advance on Palmyra through the desert from the south, and two brigades of 10th Indian Division were ordered to move up the Euphrates on Aleppo.

On the 12th June 16 Brigade left suddenly for Palestine, where they detrained at Tulkarm and marched to Beit Lid camp. Both places were very familiar to old stagers of 2nd Queen’s. On the 15th June the 2nd Queen’s, without warning, was ordered to move that evening to Deraa, just over the Syrian border and on the road and rail communications to Damascus. They reached Deraa about noon on the 16th to find the town in great confusion. The town had been captured a week earlier by the Free French who had then pushed on up the road towards Damascus. It had been bombed the previous night and there were rumours of enemy armour approaching. The garrison was very small so the Battalion was at once pushed out to take up a defensive position north of the railway station. At 4pm they were ordered on to Sheik Miskine, a village about twenty miles further north. Here they prepared to make a night attack on another village called Ezra about three miles away, but this was cancelled and they moved on again by night to Sanamain on the main Damascus road, a further fifteen miles. The Battalion had by now been two days and nights without proper sleep.

2nd Queen’s came under command the 5th Indian Infantry Brigade early on the 17th June and immediately after breakfast the order came to move at once to Kuneitra and to regain it at all costs. Although Kuneitra was only about twenty miles west of Sanamain, the approach march necessarily had to be back through Sheik Miskine, nearly fifty miles. The Battalion arrived outside the small town in the late afternoon. A supporting troop of 25-pounders and a machine-gun platoon were already on the spot, and the attack began at 5pm. ‘A’ Company secured the start line, ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies led the attack as the forward companies, with ‘C’ Company in support. The attack came under fairly heavy fire from LMGs, mortars and field artillery, but the Battalion pushed steadily on, and by nightfall the town was recaptured with the loss of one killed and twelve wounded. The enemy force could be seen moving off in the distance, but there were no mobile troops available to follow them up. The Battalion remained in Kuneitra for four days. It was a pleasant spot, an oasis at the foot of the Mount Hermon range. They were much visited by war correspondents.

Before dawn on the 22nd June 2nd Queen’s moved off to rejoin 16 Brigade, who were on the south-west approaches to Damascus. The Battalion had been ordered to clear the Kuneitra-Damascus road. With the Carrier Platoon leading, an abandoned road-block was found three miles up the road, but no Vichy French. By midday contact had been made with 2nd Leicesters near Aartouz and 2nd Queen’s took up a defensive position facing the village of Qatana, about two miles to the west. A patrol from ‘B’ Company reported that Qatana was only lightly held but that enemy armoured cars were in the area. There was quite a lot of shelling during the afternoon and evening. The next morning the Battalion advanced again in transport and passed through Qatana unopposed. The next objective was the village of Yaafour about seven miles north.

|

|

| Lt Gordon Cheston, OC the Carrier Platoon, 2nd Queen's |

Lt John Cotton, 2nd Queen's |

This moment marked the beginning of a fortnight which in retrospect came to be regarded by many members of 2nd Queen’s as the nadir of their fortunes in the Middle East. Lt John Cotton, who had joined 2nd Queen’s at El Tahag camp in March, recalls the period as “disastrous”, and indeed it was certainly unpleasant and not very successful, reducing the strength of the Battalion to 350 all ranks through battle casualties and heat-stroke. It was spent mostly in an area where there was little cover from view from an enemy occupying a dominating feature, the Jebel Mazar. It was discovered after the campaign that the Vichy French artillery fire owed its extreme accuracy to the fact that the area had been a pre-war practice range and that Point 1634 metres, the highest peak on Jebel Mazar, was elaborately fitted out as an instructional OP. Damascus had been captured by the Australians on the 22nd June after three days hard fighting involving an encircling movement by the Free French and 5th Indian Infantry Brigade. However, the advance on the coastal road to Beirut was still held up, so an advance was planned down the Damascus-Beirut road. This road was also dominated by the Jebel Mazar as it passed between Jebel Mazar and Jebel Habil before turning north-west towards Beirut. It was to provide flank protection for this proposed advance that the area around Yaafour and the northern extension of Jebel Mazar became so important.

Having passed through Qatana 2nd Queen’s debussed and deployed, the carriers moving along the road with ‘C’ Company in support, and ‘A’ Company on the right going through the hills with ‘D’ Company moving through rather more open country on the left. ‘B’ Company was left around Qatana as a firm base. Only light opposition from withdrawing armoured cars was met with until a mile short of Yaafour, where the ground became flat and open. Both ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies were held up by the fire of about fifteen armoured cars. ‘C’ Company was then put in on ‘A’ Company’s right with artillery support, and under cover of darkness entered Yaafour at about midnight. ‘B’ Company was brought up from Qatana to help ‘C’ Company hold the village whilst ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies were withdrawn to rest. There had been a number of casualties during that day, including Capt P.R.H. Kealy wounded, and ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies had been reduced to about forty effectives each.

On the 24th June the objective given to the Battalion was the main Damascus-Beirut road, on which they were then to turn left and establish a road-block. The 2nd Leicesters were to advance on the Battalion’s right. The line of advance lay up a valley completely bare of vegetation except for some camel thorn, and the only cover was an occasional stone wall about two feet high. The whole valley was completely overlooked by Point 1634 high up on the left of the advance. To have made the advance secure it would have been necessary to picquet the Jebel Mazar, but 2nd Queen’s had neither the resources nor the time to carry out such a slow operation. The Battalion therefore formed up with the carriers on the road, ‘C’ Company on the right and ‘B’ Company on the left. They were heavily shelled at the southern entrance to the village whilst moving to the start line. The carriers under Lt Gordon Cheston and Sgt Charlie Cronk showed great enterprise in engaging the more heavily armed armoured cars and greatly assisted the companies to get forward. By noon the advance had reached a crest about a mile short of the main road. Here the Battalion was held up by a considerable concentration of machine-gun fire and very severe shelling, OC ‘B’ Company, Capt C.E.W. Hull, MC, was killed and 2/Lt J.A. Benson of the same company wounded. After suffering these losses ‘B’ Company was relieved by ‘A’ Company. The enemy armoured cars withdrew at this stage and the carriers knocked out two machine-gun posts, so the situation became a little easier, but it proved impossible to push on to the objective. The Battalion had suffered considerable casualties from the shellfire, and there had been a number of cases of heat exhaustion. The Commanding Officer, Lt-Col B.C. Haggard, collapsed in the evening from a dangerous heart attack, probably brought on from a severe wound that he had received in the 1914-18 war. He was evacuated and died on his return to England. Capt R.E. Rogers was also evacuated with heat-stroke. Major R.F.C. Oxley-Boyle, MC assumed command of the Battalion.

During the night of the 24th/25th June an attack was made on Point 1634 by two companies of the 2/3rd Australian Infantry, unknown to 2nd Queen’s. This Australian battalion came under command of 16 Brigade during the temporary absence of 2nd King’s Own. Their attack was held up about a mile short of their objective. For a night attack this was a most difficult operation as the slope was very steep and pitted with crags and cavities, so that it was almost impossible for sub-units to keep in touch, even at platoon level. The first that the Queen’s knew of this attack was when they saw the Australians coming away next morning.

The Battalion was ordered to consolidate their positions in the foothills, but pushed ‘D’ Company half a mile forward onto the lower slopes of Point 1634. The next night the Australians, reinforced by a third company, made a second unsuccessful attack. This was followed by another most unpleasant day, with 2nd Queen’s deployed with three companies forward west of the Yaafour-Damascus road, and ‘C’ Company held back on the east of the road with Battalion Headquarters. The Australians were on the left directly below Point 1634. The heat was intense and the sniping and shelling was even heavier than before. However, during the day a gallant patrol from the Carrier Platoon broke through a road-block and established an observation post on the north side of the main Damascus-Beirut road in the area of Ed Dimas.

Once again on the night of the 26th/27th the Australians put in yet another attack on Point 1634 and were at last successful, being in possession of the crest and fifty prisoners next morning. But the attackers were exhausted and short of ammunition, so ‘B’ Company of 2nd Queen’s was dispatched with pack animals and supplies to reinforce the Australians. However, the enemy reacted strongly and rushed two battalions to the area in transport. These units began a counter-attack at about noon, and by 3pm the Australian company on the summit was surrounded whilst their supporting companies and 2nd Queen’s were on the lower slopes under heavy fire. A Vichy ultimatum to surrender was indignantly rejected by the company on the summit.

A platoon of ‘B’ Company very gallantly succeeded in joining this company, but since no further reinforcements could reach them, orders were given to all the elements of both British battalions to evacuate the Jebel Mazar that night under cover of darkness and take up a position along a line of low hills running north-east from Yaafour to the Damascus-Beirut road. Both the Queen’s and the Australians withdrew successfully. The company on the summit with its attached platoon from ‘B’ Company broke out and got away safely, the Queen’s platoon remaining with the Australians for some days. Sergeant Cyril Mountjoy, the platoon commander, received the MM for his fine leadership.

Unfortunately when daylight came the new positions proved to be as uncomfortable as the area just vacated, being still under full observation from Point 1634 and constantly shelled, which made movement by day practically impossible. 2nd Queen’s remained in these positions until the evening of the 4th July, when they were relieved by 2nd King’s Own, but one company was left in reserve behind the King’s Own for two more days until replaced by 2nd Leicesters. The whole Battalion then concentrated at Hame near Damascus.

The capture of Yaafour and the subsequent operations around the Jebel Mazar had cost 2nd Queen’s one officer and ten men killed, two officers and 42 men wounded, with three officers and 18 men evacuated with heat-stroke. Many others had suffered badly from the heat and sandfly fever but had carried on. Another casualty had been 2/Lt T.V. Close, who, whilst acting as the liaison officer with Brigade Headquarters, was taken prisoner. and was one of those treated extremely badly by the Vichy French. However substantial reinforcements (5 officers and 200 men) reached the Battalion whilst they were at Hame.

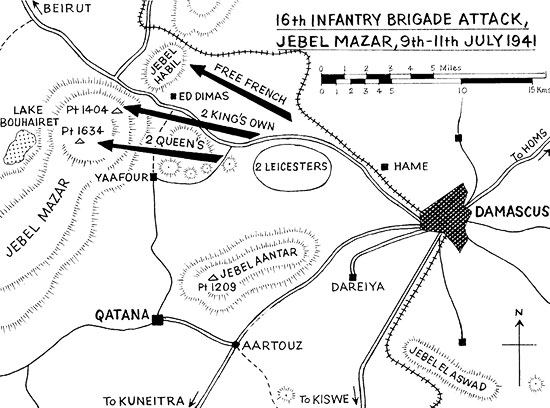

16th Infantry Brigade attack, Jebel Mazar, 9th-11th July 1941.

It was now decided that piecemeal attacks to open the Damascus-Beirut road should be replaced by a brigade operation. 16 Brigade were to attack with a Free French unit under command on the right with Jebel Habil as its objective, 2nd King’s Own in the centre aimed at Point 1404, whilst 2nd Queen’s again took on Point 1634. The start line for 2nd Queen’s was to be the same wadi which Battalion Headquarters had occupied the week before. The Battalion moved off during the evening of the 9th July, and somewhat to their surprise reached the start line without incident. ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies then made good the low hills to the front and just before midnight ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies moved through towards the objective. About l.00 am machinegun, rifle and mortar fire broke out from the mountain and continued for the rest of the night. Shortly before dawn ‘D’ Company reported that they had nearly reached the summit but had lost touch with ‘C’ Company and needed help. ‘A’ Company with a mortar detachment was accordingly sent forward to reinforce, but came under severe machine-gun and mortar fire which wiped out the mortar detachment. At noon a message from ‘C’ Company revealed that they had gone too far left and were on the western slopes of Point 1634 and north-east of Lake Bouhairet. After this report nothing was heard further from any of the forward companies. In fact the majority of these companies had been taken prisoner. The enemy had been fully expecting the attack, and when they had detected the advancing companies approaching in the moonlight they allowed the attackers to penetrate their positions and had then surrounded them. 10 Platoon of ‘B’ Company,

commanded by Lt E.B.G. Clowes, who had been sent out to try to destroy a particularly troublesome enemy mortar, came away safely after finding it to be strongly defended and been beaten off. It was not until the morning of the 11th July that the survivors of a platoon of ‘A’ Company returned, carrying their commander, Lt J.L. Halpin, badly wounded in the head, but they had no news of the rest of ‘A’ Company.

That evening the Battalion were told that they would be relieved that night by the 2nd York and Lancasters, followed a little later by another message to say that an armistice would come into effect at midnight. The relief duly took place under heavy mortar fire, since the Vichy French apparently considered it their duty to expend all their remaining ammunition. The remnant of the Battalion, 350 strong, moved back to an area about ten miles south of Damascus. A few more survivors from Jebel Mazar returned to the Battalion in the course of the next two or three days.

The capitulation terms were generous, negotiated after the allies had eventually reached Beirut and brought it under close attack during the night of the 10th July, greatly aided by a daring raid by 11 Commando, which was landed from the sea behind the enemy lines. Syria was to be occupied by the allies; all ships, aircraft, naval and air establishments were to be handed over intact; all British, Indian and Free French prisoners to be released; the choice to be given to the officers and men of the Army of the Levant either to be repatriated to France or to stay and join the Free French.

The immediate results did little to encourage belief in any French desire to see the defeat of the Axis powers. Of the 37,736 officers and men of the Army of the Levant only 5,668 opted to join the Free French, and of these only 1,046 were native Frenchmen, the rest being members of the Foreign Legion (mostly Germans or Russians) or African troops. Furthermore, it was discovered that after the signing of the armistice terms General Dentz had ordered the hasty removal of a number of allied officers and British NCOs to Vichy France, either via Athens and Germany or through Italy. 2/Lt Terence Close was one of these POWs involved. When the deception was discovered General Dentz, three other French generals and some thirty colonels and majors were arrested and it was made clear to them that they would not be released until all allied prisoners were returned from whatever location. At first the Vichy Government thought that the British were bluffing, and that they did not seriously mean to hold French senior officers against an exchange for British and Indian junior officers and other ranks. However, when General Dentz’s actions were fully appreciated and severely criticised by the American Consul-General, who had helped with the negotiations, the Vichy Government quickly located the whereabouts of all the prisoners, and they were soon on their way back to Beirut.

The 16th British Infantry Brigade was allocated the Homs area to garrison, which is about 100 miles north of Damascus. 2nd Queen’s was quartered in the Ecole Militaire in Homs itself. Here their ex-prisoners, 8 officers and 140 men, rejoined them, raising the battalion strength to 25 officers and 540 other ranks. This comparatively low figure, despite the strong draft received, was mainly due to the heavy sick rate during a very unhealthy campaign. Casualties in the final battle for Point 1634 had been 13 other ranks killed, with three officers and 32 men wounded. Subsequently 2/Lt W.J.C. Greaves, who had been badly wounded in a brave struggle against French African troops, died as a prisoner in Vichy hands.

2nd Queen’s remained in Homs throughout August enjoying good amenities and some hard training. On the 9th September the Battalion moved by MT to Jedeida, forty miles from Homs on the Baalbek road, where a big defensive position was being constructed to cover Damascus in the event of any invasion from the north. The Battalion lived in bivouacs as tentage was limited, and divided their time between digging and training.

Although the campaign in Syria had brought little honour to those involved, its successful conclusion greatly improved the allied strategical position in the Middle East. It closed the door to any further enemy penetration eastwards from the Mediterranean and moved the defence of the Suez Canal northwards some 250 miles. It also relieved Turkey of anxiety for her southern frontier, and she could now concentrate on ensuring her neutrality from those great events that were about to unfold beyond her northern boundaries. On the 22nd June Hitler had, without warning, attacked Russia.

« Previous ![]() Back to List

Back to List ![]() Next »

Next »

Related