The Middle East

The Battle of El Alamein

The 131 Brigade stayed in the ‘Hog’s Back’ position for four days. The Brigade then again took over the Munassib area, which was now fairly quiet, from 132 Brigade. Four days later the Brigade moved back in MT to Deir el Tarfa, where reinforcements joined them and they began training for their part in the coming offensive.

Group of officers with 1/6th Queen's before Alamein.

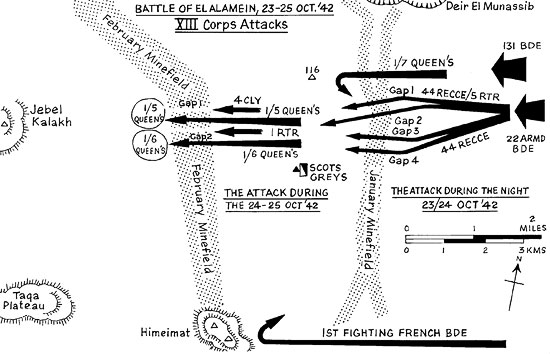

The Battle of El Alamein proved to be one of the turning points of the Second World War. General Montgomery’s plan for the battle was that the main attack would take place in the north where the defences were deepest and most comprehensive; but because of this an element of surprise could be achieved, particularly if it could be made to appear to be a feint or holding attack prior to a main thrust in the southern sector. XXX Corps, consisting of the four Commonwealth divisions and the 51st (Highland) Division, were to clear two passages through the minefields for the two armoured divisions of X Corps to pass through and shield the infantry from the enemy’s armoured formations whilst they destroyed the enemy’s infantry. The task of XIII Corps in the south was to make the enemy think that they would be making the main attack, and especially to ensure that the 21st Panzer and Ariete Divisions, deployed in the southern sector, should be held there until it was too late for them to be redeployed against the main attack. XIII Corps consisted of the 7th Armoured Division, the 44th and 50th Infantry Divisions, and the 1st Fighting French Brigade.

An elaborate deception programme was instituted with dummy stores dumps, dummy vehicle parks and tank units, a dummy fresh water pipeline, and enhanced wireless activity in the XIII Corps area. 8th Armoured Division was disbanded, but its Headquarters staff continued to maintain bogus communications traffic and simulate the movement of units in order to give the impression that the armoured component of XIII Corps had been reinforced. Somehow Axis reconnaissance aircraft always found it easier to penetrate the southern sector than to cross over into the northern sector; and of course the twin peaks of Himeimat had conveniently been left in enemy hands after the battle of Alam Halfa, from which there was a large area of visual observation! The basic ambiguity about all these helpful observation facilities available to the enemy was that the ex-British forward minefield February now formed the main Axis defensive minefield in this sector; the ex-British minefield January was now the enemy’s forward minefield; and XIII Corps had been forced to set out two additional minefields, Nuts and May, for their own defence. This made it difficult for any serious attack to be concealed, and furthermore meant that approach marches became extended affairs.

The specific task of 131 Brigade was to form bridgeheads beyond the January and February minefields between Deir El Munassib and Himeimat through which the 44th Recce Regiment, a unit equipped entirely with carriers, would pass, to be followed through by units of the 22nd Armoured Brigade as the situation permitted. If a clean breakthrough was achieved, then the armoured cars, Stuarts and Grants of the 4th Light Armoured Brigade could be sent through to drive west to the Jebel Kalakh and the Taqa Plateau. The actual gaps through the minefields would be made by Matilda tanks fitted with flails, known as Scorpions. The 1/7th Queen’s was detailed for the attack through January as the first phase of the operation, whilst 1/5th and 1/6th Queen’s would then come up on the left to cross February and form a bridgehead on the far side. The battle along the whole front was scheduled to start on the night of the 23rd/24th October during the full moon.

The task of 1/7th Queen’s was not an easy one. Their advance on foot, and that of the 7th Armoured Division units in armoured fighting vehicles, had to reach the January minefield simultaneously, so their start line had to be some 1600 yards ahead of the 7th Armoured Division’s start line. However, morale was high and everybody had been carefully briefed about the battle plan and the part that they had to play. All three battalions of 131 Brigade moved off towards their assembly areas immediately after dark on the 23rd October through gaps in the May and Nuts minefields and spread out over the desert into battle formations in bright moonlight. 1/7th Queen’s were correctly formed up on their start line at 9.30pm without incident, ten minutes before the artillery barrage was due to start. Unfortunately five minutes before Zero-hour for the attack the enemy brought shell and mortar fire down on the Battalion, and there were a considerable number of casualties. However, at 10pm 1/7th Queen’s moved forward behind the barrage with ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies leading, together with the Commanding Officer, Lt Col R.M. Burton, and his tactical headquarters.

Almost immediately the Battalion ran into difficulties because the intensity of the barrage kicked up so much dust and smoke that visibility was reduced to about 10 yards, and platoons experienced great difficulty in keeping touch. Shortly afterwards a series of wadis were encountered running diagonally across the line of advance. Lt Col Burton, with the advanced elements of ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies, pushed on very quickly and lost touch with the rest of the Battalion, and at about 10.30pm had cleared the wadis and were on a ridge just behind the barrage. A number of shorts fell amongst this party and inflicted some casualties, but when the barrage lifted they continued advancing due west and reached January. In this sector there were two belts of mines, both about 250 yards wide and 200 yards apart, which many parties from the Battalion managed to traverse. However, fixed line machine-guns and enemy defensive artillery fire caused many more casualties, including Major E.W.D. Stillwell, the 2i/c, Capt R.O. Henderson and Capt A.F.W. Parsons among those killed, with Major R. Fairbairn, OC ‘D’ Company, being badly wounded.

Lt Col Burton and his party continued to advance west, and after a further 300 yards passed out of the murk of the barrage into an area of clear moonlight. After another 800 yards he halted as he felt that he must be on his objective, Point 116, and tried to contact the rest of the Battalion, but no sign of them could be found. He then decided to move south in order to contact the recce regiment or other armoured units coming through the gaps, since he felt that he had not sufficient strength to hold the objective. They advanced several hundred yards on this bearing, and as Lt T.H. Kemp, the Signals Officer, later reported,”We appeared to pass right out of the battle.” The Commanding Officer finally decided to turn back eastwards to try to contact friendly forces, but the whole party ran into heavy machine-gun fire and Major J.C. Colebrook, OC ‘A’ Company, was badly wounded. This group was by now reduced to twenty odd men, and being completely cut off, were eventually taken prisoner. Shortly after this, however, two carriers and an armoured car approached and gave them the chance to make a dash for freedom. Capt J.R. Mills (‘D’ Company) and Lt Kemp with a handful of men managed to escape in the confusion, but tragically Lt Col Burton was amongst those killed by their Italian captors during the escape. His body was found 10 days later in a place which showed that he had found his way through the February minefield behind the enemy positions and was almost opposite the southernmost gap through the minefields. Major Colebrook died of his wounds as a prisoner.

Meanwhile the rest of the Battalion had become split up into small groups and continued to suffer heavy casualties, communications having broken down between companies and with the battalion headquarters. The Adjutant, Capt N.J.P. Hawken, and Capt P.R.H. Kealy (who had been posted across from the 2nd Battalion when they had left for Ceylon) made strenuous efforts to reform these groups in a wadi just west of the January minefields, and had collected together the equivalent of about two platoons when Capt Hawken was wounded at 3am and evacuated. He called at Brigade Headquarters and briefed Brigadier E.H.C. Frith, MBE, on the situation. Capt Peter Kealy was also wounded shortly afterwards. Daylight came, with what was left of the Battalion dug into defensive positions forming a bridgehead on the far side of January. Capt K.A. Jessup was able to bring up the carriers and mortars into this bridgehead, whilst Capt W.D. Griffiths, the Anti-Tank Platoon commander, collected stragglers at the RAP during the day with the intention of reinforcing the bridgehead. A number of prisoners had been taken during the night, and during the following day a good many more came in, mostly due to the supporting artillery fire. A number of the enemy were also killed or wounded as the Battalion cleared various enemy posts during the consolidation phase. However, before Capt Griffiths was able to lead forward his reinforcements, 1/7th Queen’s was relieved by the 2nd Buffs and moved back to reorganise in reserve.

The 1/7th Queen’s had suffered heavily in their battle against the Folgore and German 22nd Parachute Brigade units manning this part of the line. Lt Col Burton and four other officers had been killed or died of wounds, and six officers were wounded, with 179 other ranks killed, wounded or missing. However, they had secured the right flank of the XIII Corps attack, and the Royal Engineers attached to the Battalion were the first to clear a gap through the January minefield and most of the 5th Royal Tank Regiment went through.

Although the southernmost gap breached the February minefield too during the night, the light armour which got through suffered such heavy losses that the situation could not be exploited. Moreover the surviving sappers and Scorpions were now not numerous enough to complete their tasks through February before daylight, so the 1/5th and 1/6th Queen’s were not brought up to begin the second phase of guarding a bridgehead beyond February. It became obvious that the 22nd Armoured Brigade would have to spend the day ahead penned in between January and February overlooked by the twin peaks of Himeimat, since the two battalions of the Foreign Legion, under the command of the legendary Colonel Amilakvari, had failed to capture this feature during the night. During the 24th October no element of 7th Armoured Division could make the slightest move without immediate observation and response.

At about 11am Brigadier Frith and the commanding officers of the 1/5th and 1/6th Queen’s went to meet Major General A.F.’John’ Harding, GOC 7th Armoured Division, and were informed of a change of plan, which involved an attack by the remaining two battalions of the Brigade that night in order to deal with the enemy positions on the far side of February; establish a firm bridgehead; and to take their carriers and antitank guns through the two northern gaps in front of the armour, so that the tank units could debouch on the other side of the minefield as originally planned for the first night. For this operation 131 Brigade was to come under command 7th Armoured Division. Warning orders were issued to the two battalions, and the brigade commander and the two commanding officers were taken up in tanks to view the ground. A plan was then made to attack on an 800 yard front with 1/5th Queen’s on the right and 1/6th Queen’s on the left. Each battalion was to have a frontage of 400 yards, the axis of advance being gap No. 2, which was also to be the battalions’ boundary (inclusive to 1/6th Queen’s). The start line was to be some 400 yards beyond January, marked by a line of Grant tanks from the Scots Greys. Zero hour was set at 9pm, but the distances to the forming up points by march route, the arranging of an evening meal, liaison with the Royal Engineers and artillery in a strange division, led almost inevitably to a postponement of 11/2 hours.

Both battalions were in position 300 yards behind the start line at 10.15pm, and got off to an excellent start behind the barrage. Because of the good knowledge now available of the enemy’s deployment, it was possible to divide the artillery support into three parts; a reduced moving barrage, thus cutting down the amount of dust and smoke which had so hindered 1/7th Queen’s attack; concentrations on known enemy positions; and counter battery fire. 1/6th Queen’s had suffered a number of casualties from anti-personnel mines crossing January, including three officers wounded, but 1/5th Queen’s had used gap No. I through January and was unscathed. However, both battalions began to suffer casualties from the barrage, reporting that at least one gun was falling short, lifting late, or both. Each battalion advanced ‘two up’, with 1/5th Queen’s ‘A’ Company forward right, ‘B’ Company forward left, followed by ‘C’ Company behind ‘A’ Company and ‘D’ Company on the left, whilst 1/6th Queen’s had their ‘D’ Company forward right, ‘C’ Company forward left, ‘A’ Company right rear and ‘B’ Company left rear.

Battle of El Alamein.

At about 11pm the minefield was reached and crossed with little or no opposition from the enemy, although 1/5th Queen’s, in particular, suffered a few casualties from anti-personnel mines and some random shellfire. Major R.E. Clarke, the Battalion 2i/c, was one of those hit by shellfire and died later in hospital. During the crossing of the minefield it became increasingly difficult to keep touch owing to the smoke and dust, and the inner flanks of the two battalions became a bit mixed. On the far side, however, some enemy positions were encountered and overrun, with a number of prisoners taken. After advancing about 800 yards beyond February both battalions halted and attempted to dig in. 1/5th Queen’s were unfortunate in having an enemy machine-gun about 200 yards to their right front, with another enemy post nearby. Every effort was made to capture these, but they were too well sited, and the second post was wired in as well. As a result movement became impossible, and companies had to dig in lying flat on the ground. Much the same happened to 1/6th Queen’s, who were subjected to particularly heavy mortar fire.

The sappers succeeded in clearing the two gaps through the minefield by the early hours of the morning, and at about 2.30am the tanks of the 4th County of London Yeomanry began negotiating the gaps, although the pickets on which the lamps were mounted were too far apart and the spaces between were not filled with wire, which was the usual practice. As a result some of the tanks lost their way and wandered off the cleared path, blowing up in the minefield. Other tanks were knocked out by anti-tank guns sited beyond the Queen’s positions. In all the 4th County of London Yeomanry lost twenty-six of their tanks together with their commanding officer and 2i/c. South of gap No. 2 an 88mm gun was firing along the edge of the minefield, hitting tanks of the 1st Royal Tank Regiment as they came through. Highly conscious of the need to conserve his armour, Major General Harding stopped their further attempts to pass through February. This

left the two Queen’s battalions out in the open with no armour to support them, subjected to heavy mortar, machine-gun and rifle fire. In fact, since the armoured units retired back through January so as not to be exposed for a second day between the two minefields, the battalions were left some 2,000 yards in advance of the nearest support.

The Queen’s positions were so exposed that it was impossible for men to raise their heads above ground in most areas, and it was, therefore, very difficult to obtain any accurate picture of events during the hours of daylight. 2/Lt P.B. Kingsford was a platoon commander in ‘A’ Company of the 1/5th Queen’s, and spent most of the day pinned down by machine-gun fire. He has written the following account of his experiences during the 25th October :-

“The 1/6th Queen’s were on our left but were being heavily mortared during the 25th. No tanks got through to support us as the gap in the minefield was being enfiladed from El Himeimat (‘two pimples’) which had been recaptured by the Germans.

The first sign of hope was when in the evening Italian parachutists in front of my platoon surrendered. I was short of men and sent my runner (Keohane by name) back with twenty-odd POWS!

The 1/6th Battalion thought we were being made prisoners and, as a result of heavy mortar fire, they were captured. After this all the mortars came on us and we had severe casualties. We could not go forward as German parachutists had taken over the Italian pill boxes, so Colonel East decided to make a dash back when darkness came, but things got so bad that he and a handful left before dark.

I had been shot through the leg and shrapnel went into my left thigh, and I was picked up next morning and taken to enemy trenches in the rear (which we had passed earlier). When I got up, I noticed a mortar bomb stuck in the rock an inch or two from my head! It had not gone off and, in retrospect, I realised I had been temporarily unconscious when it landed.”

Many years later Paul Kingsford heard from the Ministry of Defence that Pte C.M. Keohane had been killed on that day. He can only presume that Keohane detonated a mine whilst making his way back to the platoon. The capture of some of the 1/6th that he describes probably refers to the incident when Lt Col D.L.A. Gibbs and most of his Battalion Headquarters staff were taken prisoner together with Capt I.P. Thomson and Major G.J. Collins. Lt Col Dennis Gibbs and Capt Ian Thomson escaped from their prison camp in Italy and both took an active part in the later stages of the war. Paul Kingsford spent two and a half years in prison camps in Italy and Germany.

Pte S. Gray was Lt A.C.F. Norman’s batman in 1/6th Queen’s. He remembered Lt Norman as being such a proficient officer that he always passed with top marks when he went on courses, and always got his platoon to the right place! He wrote :-

“We moved up to where the tanks were, waiting for the off. The time came for us to fix bayonets and get to the tapes. We moved off. The creeping barrage started and in no time at all there was screaming and crying out in pain as the men were walking on the anti-personnel mines. Our artillery was screaming over our heads. After a while, you could not say we got used to it, but I think our minds just blocked out all the noise, and we carried on as if we were on a stunt back home.

Going through the minefield I had a chap at the side of me with a tommy-gun. The first trench load of the enemy we came across the chap with the tommy-gun just opened up on them. They were lying on top of one another. They had no fight in them. I left him and went forward and came across another trench full. They were long trenches and held about 20 odd soldiers. They were all kneeling and leaning on one another. I would not have got any pleasure out of shooting them in the back, so I shouted and swore at them to get out. We were not allowed to take POWs back, nor were we allowed to take our wounded back. What I wanted, if I got them all out, would be to point in the direction I wanted them to go. Unfortunately for them, in front of us behind the dannert wire, the Germans were on the high ground and could see at least our shadows if not us. Then a shell came over and landed right on the enemy. It blew them to pieces, yet I felt nothing. So Imoved forward and ran into some machine-gun fire. I hit the deck and my officer was at the side of me. Every time I tried to move there was more fire. In fact it was impossible to move without being shot to pieces.

So after quite a long while lying in the open not daring to move, it was on the point of getting light. So I said to the officer, ‘It’s coming up to sun-up. Then they will pick us off’. He said, ‘Pass the word around, every man for himself, and find a hole to get into’. Strange as it seems, a cloud came over the moon, which gave us the chance to move. But as we did so, over came mortars and shells and got some of the chaps. I and another chap found an empty German trench. Mortars and shells kept coming in our direction.

Eventually we got back to our lines. There were only three of us who had been at the dannert wire and got back. They were Lt Norman, Alf Doyle, who came from Holborn in London, and myself.”

During the day General Montgomery authorised XIII Corps to break off the attack. The Queen’s battalions were much too exposed to be of any further value, and Lt Col East and Major F.A.H. Wilson, who had taken over command of 1/6th Queen’s, made arrangements for a withdrawal through February. On arrival back, however, they were told that 132 Brigade was to take over the position behind February, and the whole of 131 Brigade was taken out that night to a position behind Nuts minefield. The initial part of the withdrawals were carried out under intense fire, and much hampered by the lack of effective communications.

Once again the casualties had been severe. 1/5th Queen’s lost one officer killed, four officers wounded, three officers missing, with other rank casualties of 10 killed, 47 wounded and 53 missing. 1/6th Queen’s had three officers killed, four wounded and three missing (known to have been taken prisoner) with 5 men killed, 42 wounded and 142 missing. Many of the missing eventually proved to have been killed or wounded.

All three Queen’s battalions had successfully carried out their tasks, although in differing ways they had endured some atrocious luck. There were several instances of “if only” which could have led to outstanding success, but it appears that the gods did not favour the 44th (Home Counties) Division, and it was hardly surprising when the Division, already reduced to two brigades, was disbanded in order to furnish much needed infantry for other formations. 132 Brigade was broken up to provide British infantry battalions for Indian infantry brigades within the Tenth Army in Syria and Iraq. This reorganisation ultimately resulted in the 4th Royal West Kents joining the 161st Indian Infantry Brigade, and thereby acquiring undying fame during the Siege of Kohima.

On the 1st November the 131st (Queen’s) Infantry Brigade was transferred to the 7th Armoured Division as the Division’s lorried infantry brigade, and served with that most famous of divisions until the end of the war. This move was warmly welcomed by all the lower ranks as a RASC platoon of TCVs became permanently attached to the Brigade, and the expectation grew that the days of marching were over! However, since training for their new role was out of the question, the senior ranks viewed the future with some misgiving, although also as a challenge.

Finally, an unsolicited tribute was received a few weeks after these events from a lady living in Farncombe, who wrote to the Regimental Headquarters. Her letter reads:-

Dear Sir,

I am copying part of a letter I received some time ago from my son, Lieut. Hewett who has been in the Middle East for 21/2 years. It is about the Queen’s and I thought you might be pleased to hear it, especially as he is in the RE and therefore unbiased and sincere in his praise. He says”When I am back I will be able to tell the people in the neighbourhood how good their fellows were in the latest battle. The 44th Division covered themselves with glory. I met a lot of them before they went. Home Counties blokes, quiet and with no swank, and believe me they can fight. Good old Queen’s.”

I feel sure you will be proud to hear this and hope you do not mind my writing and telling you.

Yours faithfully,

May Ratliff

Company with 2pdr Anti-Tank guns moving up for an attack.

The final assault.

« Previous ![]() Back to List

Back to List ![]() Next »

Next »

Related