The Middle East

"Bumming" Across The Desert

On reaching Tobruk 131 Brigade had been lorried infantry for two weeks. At that time lorried infantry were still a recent innovation, and although 131 Brigade was not the first brigade to take on the role, there were no training manuals on the subject, and nobody had any very clear ideas about the tactical handling of such a formation. Of course infantry had used MT tactically in the desert, e.g. the 16th British Infantry Brigade at Sidi Barrani, but such opportunities were rare, and usually MT was used for approach marches before making the final deployment by marching on foot. Up to the time of El Alamein the infantry incorporated into armoured formations were motorised battalions with an enhanced establishment of carriers, anti-tank guns and portees, and the addition of scout cars for use as command vehicles. Such motorised battalions were invariably provided by the rifle regiments, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps and the Rifle Brigade, and advanced in company with tanks, or even sometimes fought alongside tanks, since their vehicles provided some degree of armoured protection. In defence their anti-tank guns were often used as a gun-line behind which hard pressed armour could retire, a tactic learned the hard way from the Afrika Korps. However, there were never enough motorised battalions available to be an effective support. Lorried infantry was the cutprice alternative to the motorised battalions. The establishment remained the same as for conventional battalions, but Royal Army Service Corps troop carrying vehicles (TCVs) were permanently attached. A TCV was a 3-tonner fitted out with a row of seats down each side of the load-carrying area, and a Bren-gun mounting behind the cab. Each TCV carried half a platoon. This arrangement certainly gave the lorried infantry unit mobility, but it did not give that unit the tactical ability to travel near tanks nor to give immediate support on ground secured by the armour, unless the enemy had been chased away beyond the effective range of machine-gun or small arms fire.

|

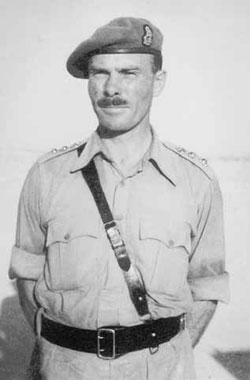

| Lieutenant Colonel L. C. East, DSO CO 1/5 Queen's . |

It would appear that Lt Col Lance East was the first person to give some thought to the tactical movement of his unit across the open desert. Copying a plan which he first saw used on the open plains of India 24 years previously, he instructed 1/5th Queen’s to move in squares, with a company at each corner and battalion headquarters in the middle. They stayed in these self-contained company packets during the nights. It was not long before the brigade group adopted a large and flexible square when on the move, with the battalions, protected by their own anti-tank guns, forming the front and flank faces, and the artillery, the 53rd Field Regiment RA, the rear face. Within the square the Brigade Headquarters and administrative services travelled. Vehicles by day were about 200 yards apart.

A start was usually made before dawn, guided by the lights of designated navigators whose task was a skilled speciality carried out by ordinary or by sun compass. The first halt was for breakfast, a brew of hot tea and porridge, tinned sausage or bacon and perhaps an egg bought from some Arab (who had the trick of appearing from nowhere out of an empty landscape!), then on again until lunch, usually tea only as it was too hot to eat. On arrival at the destination came the main meal, thankfully consumed after the flies had disappeared, consisting nearly always of stewed tinned meat with tinned vegetables, washed down with the inevitable strong hot tea.

During the pursuit the battalions of 131 Brigade endured a hand-to-mouth existence, since the progress of 22nd Armoured Brigade was not unnaturally the Divisional Commander’s main concern, so if any logistical sacrifices were required, the infantry made them. Inspite of the monotony of the food, the men were very healthy. Deficiencies in the diet were made up by vitamin pills. Flies were a continual nuisance and caused the most common complaint, a mild form of dysentery. There were also some desert sores and jaundice. Dust storms, besides being most uncomfortable, sometimes caused inflamed eyes. But when it was not raining, the weather was nearly always crisp and pleasant. Everyone was exhilarated and excited, and there was little grumbling.

When the battalions went into leaguer at nights the units closed up to five paces between vehicles, and everyone dug slit-trenches in which they normally slept. Patrolling was restricted to searching the immediate area of the leaguer and for ascertaining the best sites for posting sentries, Except at the times of the full moon, night descends quickly, the dark impenetrable. Lt Derrick Watson of ‘A’ Company, 1/5th Queen’s recalled that he suffered the most frightening experience in the campaign when he got lost no more than 50 yards from his company. “I had attended Captain Russell Elliott’s ‘O’ Group in his bivvy to receive orders for the next day to move off in convoy at first light. Before retiring for the night, I decided I must go for a walk with a shovel, and because I was still shy about this, I walked at least 50 yards into the night. It was as black as pitch, since darkness comes down swiftly in the desert - there is no twilight. Having done the business and buried the evidence in the interests of hygiene, I realised I did not know which way to turn for the return journey. No more than 50 yards away was the company, some 120 of my brothers-in-arms, sleeping the sleep of exhaustion, but in no direction was there sight or sound of them. In momentary panic I shouted ‘Help!’ once, but did not repeat it. Imagine the humiliation if the whole company stood to because their junior platoon commander was lost 50 yards away. I sat down for about 10 minutes and calmed myself, then worked out a plan. I would pace out 50 paces in the direction I thought the company was, marking my path with the shovel. If still no sight or sound, I would retrace my steps along the marked path and try the same thing in another direction. I took the first 50 paces - lo and behold, there was a bivvy with a light in it. I pulled the flap back to see the furious face of Captain Elliott I had left some half-hour previously.”

And so in this fashion 131 Brigade obeyed the order “Keep the wheels moving” and on two occasions covered over 100 miles a day, driven by the splendid drivers of the 507th Company RASC commanded by Lt John Mansfield.

Bath night in the desert.

'C' Company 1/7thQueen's brewing-up at a halt.

« Previous ![]() Back to List

Back to List ![]() Next »

Next »

Related