The Middle East

There's A Long, Long Trail A 'Winding

On the 21st November 131st Brigade Headquarters and 1/7th Queen’s left Tobruk to occupy Benghazi. They moved fast on good roads, covering 250 miles on the first two days. The desert had been left behind, with the country becoming dotted with pines and scrub reminding many of the Surrey commons. Effective air cover from the RAF was no longer available since the captured airfields were not yet operational, and enemy air attacks became frequent. In one of these Capt H.C. Albery received wounds from which he died. The second night was spent at Barce, in the middle of a well cultivated plain containing the white farm buildings of Italian settlers. The road from there led over the Tocra Pass, which had been thoroughly demolished and mined. Nevertheless the remaining sixty miles to Benghazi were completed by the early afternoon of the 23rd November. ‘A’ Company was sent to the docks whilst ‘C’ Company became the guard for the advanced headquarters of XXX Corps, which, under Lieut-General Oliver Leese, was now taking over the pursuit from X Corps. Consequently 7th Armoured Division came under command XXX Corps. The remainder of the Battalion with Brigade Headquarters went into the Italian barracks in the town.

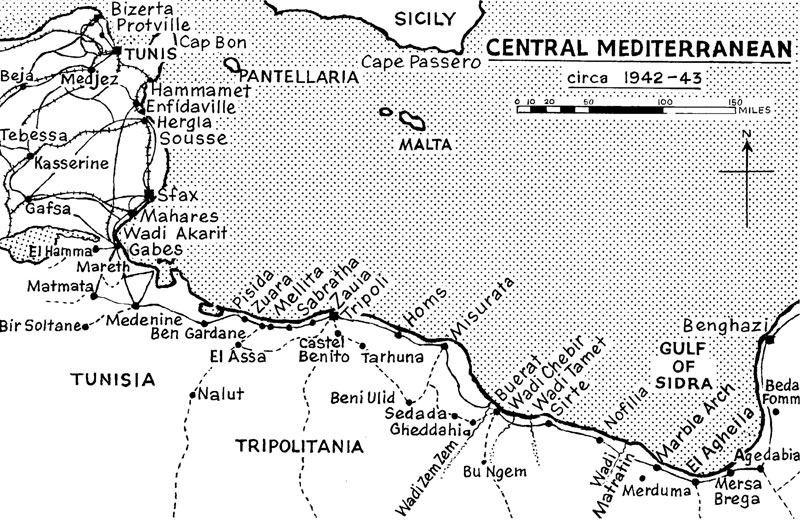

Central Mediterranean.

(Click image to view enlarged)

The next day 1/5th and 1/6th Queen’s were also ordered up to Benghazi. En route both battalions were diverted to secure the important airfield at Sidi Magrun, about 50 miles south of Benghazi, and on their way there the 1/5th Queen’s was bombed, suffering some casualties. On reaching the airfield they dug in. It was found that water was extremely scarce in the area, but eventually some drinkable wells were located by the intelligence sections. They were back in desert conditions.

|

| Brigadier L. G. Whistler, DSO Comd 131 Brigade. |

XXX Corps now consisted of the 7th Armoured Division, the 51st (Highland) Division, and the 2nd New Zealand Division. The 8th Armoured Brigade replaced the 22nd Armoured Brigade in 7th Armoured Division, with the 4th Light Armoured Brigade again being lent out to the New Zealanders. Because of logistical difficulties the advance to Tripoli was to be XXX Corps’ battle, and the first objective was to push the enemy out of his positions around Mersa Brega, and if possible to encircle him in his main defence line at El Agheila. General Montgomery was determined that this position should not this time stop the Eighth Army’s further advance.

On the 28th November the 1/5th and 1/6th Queen’s received warning orders to rejoin the Division south of Agedabia, but the supply situation was again becoming difficult, and they were sent instead to join the 1/7th Queen’s in Benghazi to help in the unloading of vital stores. During the time that 131 Brigade was concentrated in Benghazi a new Brigade Commander, Brigadier L.G. Whistler, took over. Brigadier Whistler had been lately CO of 5th Royal Sussex and was an old friend from 44th Division days. At about the same time Lt Col E.P. Sewell, CO of 1/6th Queen’s, was promoted, and Lt Col R.J.A. Kaulback was appointed to command. Lt Col R.H. Senior, DSO, had returned from commanding the 5th Royal West Kents a few weeks previously, and was commanding 1/7th Queen’s. 131 Brigade remained working in Benghazi, under intermittent air raids, until the 12th December, when they left to take part in the attack planned for the 14th December on the Mersa Brega-El Agheila positions.

The plan for this attack was the first of many similar plans made to eject the Axis rearguards from a series of defensive positions going back to Tripoli and beyond. The 51st (Highland) Division on the coast was to deliver a frontal attack with the 7th Armoured Division on their left, whilst the New Zealanders made a wide turning movement through the desert to the south, aiming to come up to the coast road well behind the El Agheila position. 131 Brigade prepared to take over from the 1st Gordons on the 13th December, but the preparations for the attack had alarmed the enemy, and in the early hours he started to withdraw, leaving a mass of mines and booby-traps behind. Rommel had received a most welcome arrival just after El Alamein when Generalleutnant Karl Buelowius took over as Chief Engineer to the Panzerarmee Afrika; for this little man was a positive genius at demolitions, booby-traps, and any device which would prove a nuisance and so delay a pursuer. From this time onwards the influence of this amazing military engineer was to be frequently experienced.

On this occasion, despite the mines, 8th Armoured Brigade managed to follow up the enemy closely, working their way forward over the difficult sandy and marshy ground slightly inland, with 131 Brigade following. The 51st Division was held up by the mines, so 7th Armoured led the advance until the 15th December when the armour engaged the main enemy’s defences south-west of El Agheila, where they were held up by a strong position covering an anti-tank ditch with an impassable salt marsh on the flank. 131 Brigade were called forward for a night attack at this stage, but had fallen back some miles because of the difficult going, so it was a fine achievement that they were able to get up to their start line and launch the attack on time. The battalions debussed on the start line five miles from their final objectives, and by chance a few hundred yards inside Tripolitania, with 1/6th on the right covering the front between the coast and the road, 1/7th astride the road itself, and the 1/5th in reserve. The leading battalions moved by bounds of about a mile. However, it soon became obvious that the enemy were pulling out, and although the 1/7th Queen’s encountered some tracer machine-gun fire, and there were a few casualties from mines, both battalions reached their final objectives during the night, where they dug in, in pouring rain and great discomfort.

Next morning 8th Armoured Brigade passed through along the coast road and by the evening had captured the landing grounds at Marble Arch and Merduma, making contact with the New Zealand Division coming up from the south. The whole operation resulted in the enemy losing 20 tanks and about 500 German prisoners were taken.

On the 17th 131 Brigade moved up to the Marble Arch area, where the large monument to Marshal Balbo was visible for miles looking completely out of place surrounded by the desert. Here the Queen’s battalions dug in covering the landing ground and the coast road, but on the 20th December they moved on, passing through the New Zealanders, to Wadi Matratin, where they prepared a defensive position and, when time allowed, bathed in the clear, cold waters of the Mediterranean. To ease the supply situation the small beach of Ras El Ali was brought into use for the unloading of stores by lighter. ‘C’ Company, 1/7th Queen’s, under Capt P.C. Freeman, was sent to help in this work, which required the men to strip and work all day in the chilly water, enduring considerable discomfort and hardship. When the work was finished the officer in charge of the unloading reported to Brigadier Whistler that “The work done by the men of the 1/7th Queen’s was outstanding. Quite apart from the work being uncongenial, to say the least of it, it appeared that every Queen’s man not only realised he was doing a big job towards ultimate victory, but was quite determined he would get it done inspite of the conditions. Without a doubt these men by their example and without persuasion induced others to undertake similar hardship with hardly a grouse. I would be grateful if you would convey my thanks to the officers and men and tell them that their efforts speeded up a programme which may vitally affect future operations.”

Inspite of these difficulties the RASC managed to get up ample supplies for Christmas, and General Montgomery decided there would be no fighting on that day! The 11th Hussars provided a screen by shifts, whilst the rest of the Eighth Army had a fantastic meal of fresh pork with as many trimmings as possible, including beer. Generals Montgomery and Leese visited 131 Brigade during its stay at Wadi Matratin, Montgomery remarking that they were “a good, tough body of men.”

On Boxing Day the Brigade moved forward to relieve the New Zealanders. 7th Armoured had taken the 4th Light Armoured Brigade under command again in the Nofilia area, and had managed to manoeuvre a small enemy force out of Sirte by threatening his flank and rear with strong armoured car patrols, but the advance had come to a halt when contact was made again with the enemy’s main forces preparing another defensive position in the Buerat area, with such armour as he had available covering his right flank. 131 Brigade moved through Sirte along a road still dangerous with mines and under occasional air attack, and on the 29th December took up positions as the most advanced troops, except for armoured car patrols, of the Eighth Army.

Entering Sirte.

The Brigade’s main positions were along the line of the Wadi Tamet, with a screen of carriers and antitank guns forward some 10 miles further west on the Wadi Chebir. Here a halt was called since it was considered that at least four divisions would be needed to be certain of breaking the Buerat Line, so the 50th Division was to be sent up to reinforce XXX Corps, and X Corps, consisting of the 1st Armoured Division and the 4th Indian Division, was to come up to the El Agheila area. The logistic calculations made it quite clear that once the Eighth Army moved forward against Buerat there would be only ten days to reach and secure a new source of large-scale supply - Tripoli. The Queen’s battalions therefore dug in at Wadi Tamet and remained quiet and unaggressive in accordance with their orders. The weather was unpleasant with gales and dust storms. The enemy air force was at first active, but gradually as the RAF came forward into the captured airfields the attacks lessened.

The enemy had chosen to make their next stand just behind Buerat, about 40 miles west of 131 Brigade’s positions on Wadi Tamet. Further west in the Tarhuna hills, overlooking the Tripoli plain, there was a much better position which had been more fully prepared. General Montgomery was most anxious to prevent the enemy retiring to Tarhuna, since such a move would most probably disrupt any programme to capture Tripoli within the 10 days time scale for the logistic plan. Unfortunately the preparations for the attack received an almost catastrophic setback at the beginning of January when a severe gale swept into the Benghazi area badly damaging the port and shipping, thus cutting down the intake of supplies to 1,000 tons a day, only one third of the planned quantity required. General Montgomery modified his plan, therefore, by cancelling 50th Division’s move into XXX Corps, and grounding X Corps at El Agheila, ordering it to hand over most of its transport and tanks to XXX Corps. The final plan was that 51st Division with tanks from X Corps in support would advance along the coast, while the 7th Armoured Division and the 2nd New Zealand Division would outflank the enemy through the desert to the south, moving via Beni Ulid and aiming for Tarhuna. The enemy had by now sent back most of their infantry and held the Buerat position mainly with 21st Panzer in the north and 15th Panzer in the south.

On the night of 11th January the 131st Brigade Headquarters and 1/6th Queen’s moved to a concentration area to the south, where they were joined on the 13th by the rest of the Brigade. ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies of 1/7th Queen’s were detached for special duties, so a battle group consisting of ‘C’ Company, the Carrier, Mortar and Anti-tank Platoons plus the Battle Patrol was formed under the command of Major W.D. Griffiths and came under orders of the 1/5th Queen’s. The remainder of 1/7th Queen’s moved with the divisional rear echelon. As soon as the Brigade was concentrated, and had received 10 days rations, it moved forward to cross the Wadi Chebir, which was achieved with some difficulty, a number of vehicles being bogged down. Next day they advanced about another 30 miles, where the whole Division was concentrated with the New Zealanders on the left.

The Tripolitanian desert which the outflanking divisions were now to cross was quite different from the level stretches of stony sand in Cyrenaica. Near the coast road there was deep, soft sand and further inland a mass of rocky hills. Every few miles there were deep, almost impassable, wadis running down to the sea. It was waterless and mostly barren and uncultivated. On the night of the 14th/15th January the advance proper started with a night march along a marked and lighted route. At midnight the Bu Ngem track was reached and the 8th Armoured Brigade formed up on it, with 131 Brigade to the north-east. At first light they moved forward and found the enemy holding the Umm Er Raml Ridge. A tank battle took place, with losses on both sides, and 131 Brigade came under accurate fire from the direction of Gheddahia. Major General Harding felt pretty certain that the enemy had taken enough punishment from 8th Armoured Brigade during this first encounter and that he could be encouraged to withdraw during the night, so he ordered some particularly active patrolling while the tanks were replenished with fuel and ammunition. The carriers of 1/6th and 1/7th Queen’s under Capt K.D. Kettle patrolled forward vigorously, therefore, and encountered considerable antitank fire. Sergeant Robert Hill of the 1/6th won a MM when he led a patrol of two carriers during this engagement, and has left an account of the action:-

“I was in the lead Bren-gun carrier. As we advanced everything was so quiet it seemed unnatural. Then all of a sudden artillery opened up. The second carrier was hit, so we picked up the crew, one of whom was wounded. We carried on advancing at a faster speed and found out where the enemy were. In doing so we came up a wadi and as we got to the lip we spotted an enemy machine-gun nest. The corporal alongside me popped a hand grenade into the nest, getting rid of that one. We turned to our left flank and carried along the lip of the wadi and wiped out four more machine-gun positions and captured four prisoners before returning to our lines. The chap who was wounded died on the way back.”

At nightfall, in accordance with General Harding’s hunch, the enemy retired and 131 Brigade occupied the ridge, with 1/6th Queen’s providing an anti-tank screen with three battle groups under Majors J.H. Mason and R.d’A. Mullins, and Capt T.J. Kilshaw. It became noticeable from this time that tactics were changing, with more use being made of composite battle groups, which were small copies of the previously widely used ‘Jock Columns’.

Next day the whole southern force crossed the formidable Wadi Zem Zem unopposed. The crossing of this wide wadi by so many vehicles created enormous clouds of dust over large areas of the desert. There were repeated Stuka attacks on the Brigade, and it only covered some 12 miles beyond Wadi Zem Zem before going into leaguer for the night at Wadi Gobbeir. On the 17th the advance was at first delayed by the wadi south of Sedada, over which the bridge had been demolished, but once 8th Armoured Brigade was across there was a good stretch of track and at dusk the leading elements of the Division were established north of Beni Ulid, and reporting that that town was crowded with enemy transport. The 1/6th Queen’s spent much of the day helping to construct an airfield, which was at once occupied by the RAF. There were no longer the numbers of airfields which had been available on the old battlefields of Cyrenaica, so such improvised airfields were essential for the provision of close air support.

Unfortunately, in complying with General Montgomery’s demand for speed, the Division ran into appalling country, reported as the worst in its desert experience. It was a plain of jagged rocks and boulders, cut by deep wadis, and the wheeled transport was reduced to a crawl. By the evening of the 18th January the Division was so strung out that the 1/5th and 1/6th Queen’s had to form an anti-tank screen to protect the rear echelons. On the 19th January 8th Armoured Brigade hooked round Tarhuna and made contact with the outposts of the main enemy defensive position west of the town. They were ordered not to attack until the New Zealand Division had come up on their left, and this gave the rest of the Division time to close up. The 1/6th Queen’s occupied Tarhuna. Unfortunately, Major General Harding was badly wounded carrying out a reconnaissance and Brigadier ‘Pip’ Roberts, commanding 8th Armoured Brigade, took over as divisional commander. That night the enemy withdrew from these covering positions, and retired to the main Tarhuna Hills position where the road descended to the Tripoli plain through a pass. This required 131 Brigade to make a night attack through the hills on either side of the pass. The 21st January was spent in preparations for this attack.

During the night of the 20th/21st Major Bill Griffiths’ 1/7th Battle Group, reduced to just the Carrier Platoon (Capt Peter Freeman), the Mortar Platoon (Lt G.W. Bevan), the Battle Patrol (Lt T.C. Godfrey), but reinforced by a machine-gun platoon of the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, advanced 15 miles through very difficult country, digging their way across wadis, until they were well behind the enemy positions. From here, throughout the 21st they attacked enemy gun positions, set fire to transport vehicles, and shot up any troops encountered. These actions, carried out without any possibility of support, greatly contributed to the success of the main attack by disrupting enemy movement. The main attack, entailing an approach march of 6 miles and a night attack of another 8 miles, went like clockwork. With 1/5th Queen’s advancing on the south side of the road and 1/6th Queen’s on the north side, the enemy started to withdraw, so the battalions had little difficulty in clearing the hills and occupying the pass. The 1/5th encountered some vicious mortar fire and Capt C.A. Howard, one of the few survivors from Dunkirk days, was killed and four others wounded. Pte Jack York gives a dramatic account of Capt Howard’s company’s part in this action in his memoirs ‘Desert Rat Brigade’:-

“Our battalion was ordered to attack the high ground to the left of the Pass, with a composite force of a rifle company and some HQ personnel. Because of the urgency of the situation, we set off straight away at midday for the foothills, without food, blankets, greatcoats or haversacks.

For this operation my companion George and myself were attached to the rifle company as wireless operators, and our Signals Officer was with the HQ section. Our wireless sets were linked to a more powerful set at the foot of the Pass, which was also in touch with Brigade and the artillery.

The afternoon sun was hot as we clambered up the rocky slopes, probably looking like a swarm of ants from the plain below. As I glanced upwards I could see a mass of striated rock, crisscrossed by small channels, and mostly covered with sage, coarse grass and camel thorn. It was hoped that once we had climbed this high escarpment we would be in a position to spot the enemy and call upon the artillery for supporting fire.

Slowly we worked our way higher up the rugged cliffs, holding onto outcropping rocks and grasping wiry sage and brush. Halts were frequent to gulp down life giving air and wipe the perspiration from our streaming faces, but we knew we must get on. Not many hours left before sundown.

At last after a long weary struggle we neared the top of the high ground, feeling exhausted and dizzy from the heat and lack of food. The Captain allowed us a few minutes rest, and then off we went again, at last bearing right towards the ridge that overlooked the Pass, through a wide ravine covered with scattered pieces of rock, with the ground levelling out.

Suddenly mortar bombs started to explode across the valley with an echoing crash, sending waves of

compressed air, flying stones and shrapnel over a wide area. My companion and myself crouched down in a small gulley, wondering what would happen now. The Captain shouted over to us to get the artillery to send over ranging shots, giving us details of the target. Soon a ten minute barrage was laid on, and the missiles came moaning and fluttering over the hills, to land with hollow thuds among the enemy trenches, which were barely visible in the distance.

‘Well done’ shouted the Captain, and taking George with him, he advanced with a platoon of men up the gorge towards the enemy. I followed some distance behind, carrying the wireless set, and pretty soon could hear the vicious sound of enemy Spandaus mingling with the explosions ahead. Each burst of fire sounded like a piece of cloth being ripped in half as a hail of lead swept down on the attackers. For the most part the enemy seemed to be firing too high, but one or two men were wounded and I could hear them shouting for help. Medical orderlies crawled towards them.

The Captain, George and another soldier had taken refuge behind a big rock, and blood was pouring from a wound in the Captain’s left arm. This was quickly bound up by the signaller, who then volunteered (much to the Captain’s surprise) to run back to my wireless set and lay on a barrage of smoke shells. The Captain reluctantly agreed, and I soon saw him approaching, dodging round obstacles, and slipping and sliding over vegetation. Just before he arrived he was slightly wounded in the leg, but delivered the message safely.

Soon the ridge ahead was wreathed in smoke and the Captain, with another officer and about twenty men moved forward until they were able to lob grenades round the enemy positions. Leaving my companion with the set, I moved up towards the ridge and tried to catch sight of the Captain. As the smoke cleared I could see him running towards a large hole from the flank, revolver in hand, and saw black huddled shapes crouching behind a machine gun. Suddenly there was a yellow flash and then an indescribable mêlée as more men rushed up. A fearful agitation and twisting of bodies as the smoke cleared. One man in a frenzy of excitement, fear and relief, plunged his bayonet incessantly into a dead German soldier. ‘Take that you bastard’ he shouted over and over again until restrained by an NCO. I understood how he felt, but on the other hand that poor dead soul was somebody’s mate, just like George was mine.

After a few minutes it was all over, and in one or two trenches lay upturned machine-guns resting on dead and mutilated bodies. The men just lay gasping on the ground after their ordeal and orgy of killing. We found the brave Captain dead beside a weapon pit, his hands pressed to a hole in his stomach.

As I walked further along the ridge with an officer we found two trenches which had received direct hits from our artillery; the occupants were just dark, grotesque shadows, motionless in the pale sunlight.”

Capt Howard was awarded an immediate MC posthumously on the 17th February,

At dawn 8th Armoured Brigade passed through and drove out across the flat, clumpy turfed plain. The two battalions remained guarding the Pass, which soon was the scene of a large traffic jam, mostly caused by unofficial sightseers intent upon being the first into Tripoli! At midday 8th Armoured Brigade bumped into the enemy rearguard in front of Castel Benito, and 131 Brigade was called forward. Their lorries were at the far side of the Pass, but the Divisional Provost Company forced all other vehicles to the side of the road, the 507th Company’s lorries were rushed up, and the battalions embussed in front of a crowded audience. It was reported as being a model of quick and efficient movement of lorried infantry, but some rather rueful spectators spent a frustrating time getting their bogged vehicles back on the road!

In the late afternoon 1/5th and 1/6th Queen’s were again drawn up for the second time in 24 hours and ready to start their attack, when it was reported that the guns which had been holding up 8th Armoured Brigade were withdrawing in the last of the light. However, patrols from the battalions soon found that the enemy were still in position, and the attack was sent in. Two large anti-tank ditches and two belts of wire were crossed in the darkness without opposition, and at 3.30am green Verey lights from the Battle Patrol of the 1/6th Queen’s, working ahead under Lt V.G. Docton, gave the news that Castel Benito was clear. They found a large notice on the outskirts which read “Tommy, we shall return.” The 1/5th formed up in threes on the road and marched into the town, establishing themselves in the buildings whilst the Pioneer Platoons searched for booby-traps.

The 11th Hussars were the first into Tripoli in the early morning of the 23rd January, four hours before the tanks of the coastal column, which had been held up by extensive mining and demolitions. It was three months to the day since the start of the battle of El Alamein, and the 7th Armoured Division had advanced over 1,400 miles, usually at or close to the front of the pursuit. However, 131 Brigade was not given the chance of seeing the sights or enjoying the comforts of Tripoli. The enemy rearguards had not retired far, and the 7th Armoured were detailed to be the covering force while the 51st (Highland) and the 2nd New Zealand Divisions reorganised. The 1/5th and the 1/6th Queen’s with Brigade Headquarters skirted round the city and moved on to Suani Ben Adem, where they reconnoitred defensive positions, but bivouacked on the large farms or in the woods with ample water, fresh vegetables and wine. 1/7th Queen’s Battalion Headquarters, Bill Griffiths’ Battle Group, and the other detachments came up too, so the Brigade was again complete.

There they received some excellent news. When allocated to 7th Armoured during El Alamein the Brigade was regarded as merely ‘temporaries’; now they were told that they were permanently part of the Division, the oldest and most experienced in the Eighth Army. Units and formations did not get to wear the Rat firmly unless they had earned it; obviously the Queen’s Brigade, as it was now generally called, was reckoned to have earned it.

« Previous ![]() Back to List

Back to List ![]() Next »

Next »

Related